Another Birth, Other Words: Queering the Poetry of Forough Farrokhzad in Translation

The following is a guest post by Nazila Ghavami Kivi, an editor of Danish queer feminist magazine Friktion, where the piece was originally published in Danish.

In the piece, Kivi discusses the challenges of translating poetry from the gender-neutral Persian language into Danish and the queering potential of poetry that transcends language, time and traditional gender roles.

Recently, the Swedish Academy responsible for the dictionary of Swedish language added the new gender neutral pronoun hen to the newest edition of their work. The news reached international media and reaffirmed the idea of Scandinavian countries as being the ‘frontrunners of gender equality.’

The application of the gender neutral pronoun isn’t all that new, though. It has been a subject of debate among feminist-leftist circles since the 1970s. Swedish kindergarten Egalia even applied the use of hen back in 2011. Egalia’s mission to undo gender stereotypes entailed among other things the substitution of the gendered pronouns han and hon (he and she) with the gender-neutral neologism hen.

The Scandinavian narrative of progressiveness and gender equality isn’t without its challenges and controversies, however. Internal disputes within leftist-feminist circles suggest that some see the gender neutral pronoun as a liberating panacea, bound to revolutionize binary gender roles, while others view it as an unrealistic utopian project that will only serve to blur actually-existing inequalities. Semantics won’t fix the lived experiences of sexism, they argue.

What those opposed to linguistic gender neutrality forget, however, is that this trend is often not nearly as ‘exotic’ or foreign a phenomenon as is often cast. You don’t have to travel farther than Finland — Sweden’s neighbor — before you encounter a gender-neutral language, where the neutral (and only) 3rd person pronoun is hän. This word has served as an inspiration for the Swedish equivalent: hen and the Danish: høn.

Even further afield, another language remotely related to Danish with shared Indo-European roots is Persian, in which some of the oldest and most influential literature in history has been written. Throughout history, Persian’s lack of gendered pronouns has allowed for the production of subversive texts that have confounded and enchanted readers and leaders alike.

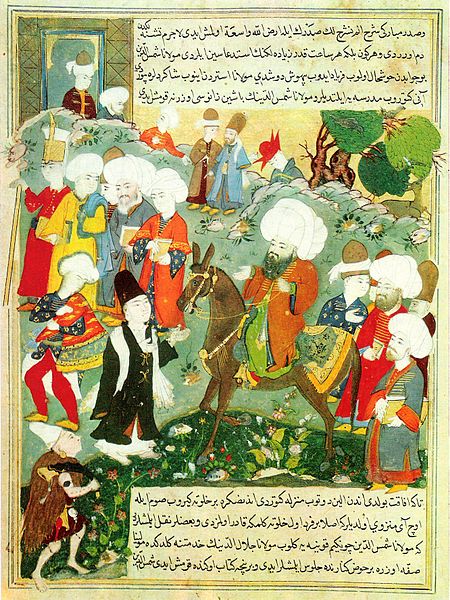

The world-renowned Sufi poet Jalal ad-Din Mohammad Molana Rumi, who lived in the 13th century and wrote in Persian, is often brought forth as an example of this subversive poetic tradition, where the Persian neutral pronoun ou (او) allows for a wide array of interpretative possibilities. His object of desire could be a monotheistic God, a deity of the earth, a woman, or his friend and mentor Shams-e-Tabrizi.

Although some read his poems as homoerotic, there is no known proof that Rumi was homosexual or had a physical relationship with his mentor, Shams. What is beyond dispute, though, is their intense love and admiration for each other.

While some call it wishful thinking or a product of the ‘modern queering’ of Rumi to read his poetry as if it was written by a contemporary gay or bisexual man, it is equally reasonable to question the heteronormative readings of 13th century poetry, written long before the dominance of 19th and 20th century binary gender identities. The possibility of Rumi having been read and translated in a heteronormative light becomes even more probable when considering other cases of heteronormative interpretations of historical sources.

Modern Assyriologists’ readings of ancient Babylonian poetry suggest that transgendered or gender transitive identities have often been erased by Orientalist readings of the original writings. Instead they have been re-cast as prostitutes, eunuchs, or “hermaphrodites” according to the Orientalist views of the ‘East’ as sexually deviant and perverted.

These ambiguities and different modes of interpretation are not limited to older literature. Modern Persian poetry, she’r-e no, that was first introduced by Nima Youshij (1895-1960) during the early part of 20th century brought new rhymes, rhythms, and techniques as well as more social and political subjects to Persian poetry.

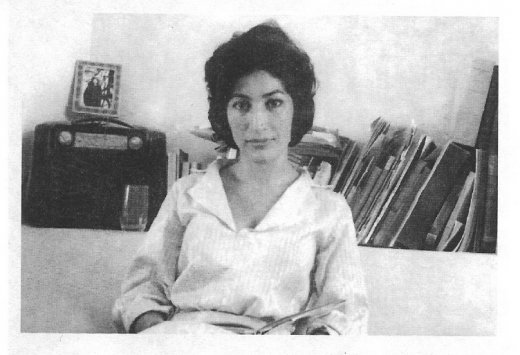

While Youshij is considered the founder of modern Persian poetry, one of the most well-known and internationally acclaimed representatives of Iranian modern literature is the controversial poet and filmmaker Forough Farrokhzad.

Born in Tehran in 1934, Farrokhzad managed to challenge all reigning norms, both in her private life and in her work as an artist. She divorced at 18, wrote poems about desire and eroticism, shunned literary traditions, and directed the acclaimed documentary The House is Black about life in a colony reserved for lepers in Iran. She died in a car accident at the young age of 32.

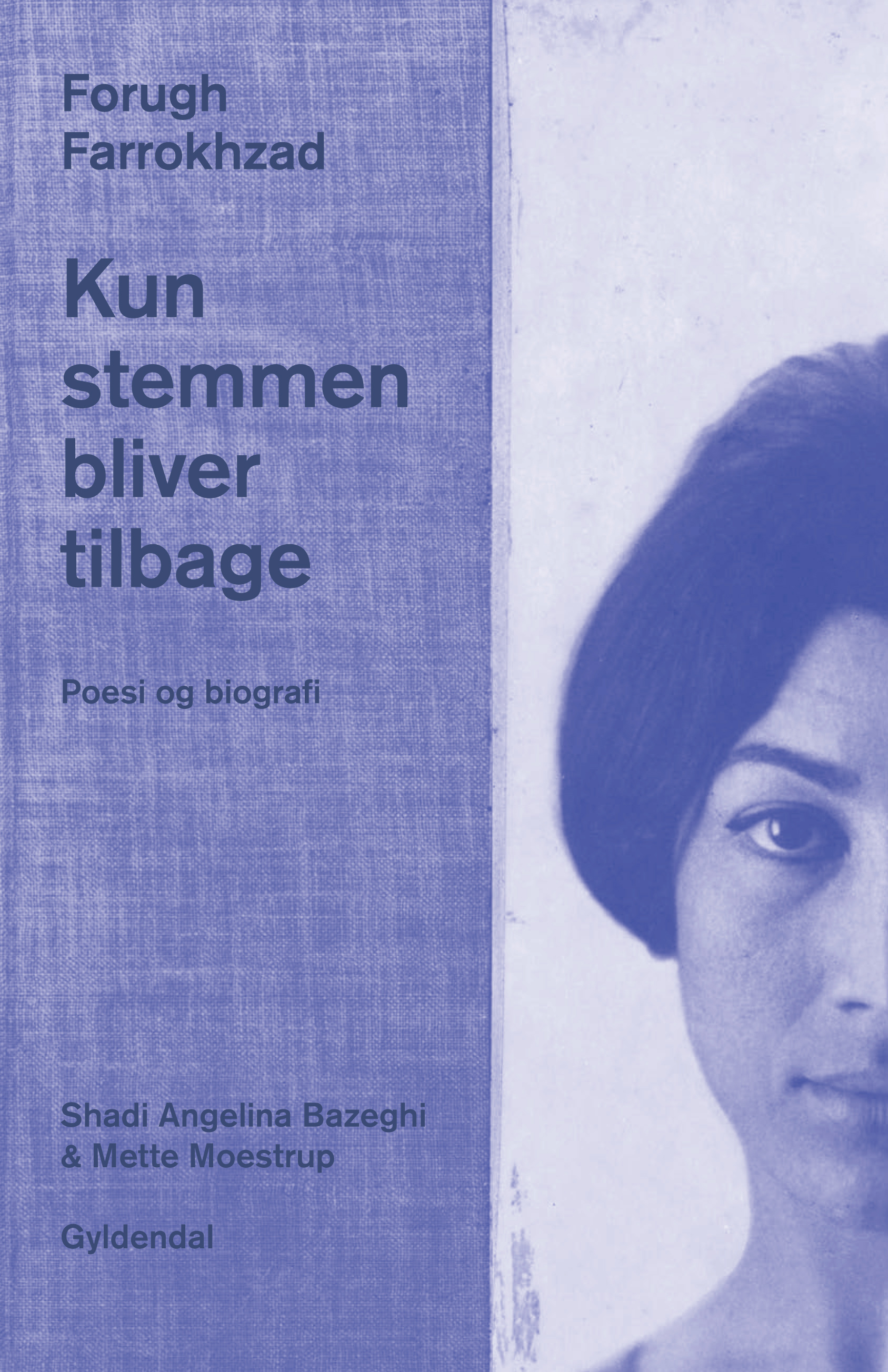

I spoke to poet and writer Shadi Angelina Bazeghi about the challenges in reading and translating Farrokhzad from a gender neutral language to a gendered one. Along with Danish author Mette Moestrup, Bazeghi has written Kun stemmen bliver tilbage (Only the Voice Remains), the first thorough introduction to Farrokhzad for a Danish audience, including some of Farrokhzad’s prose and her two last poetry collections. Bazeghi has been in charge of the translation and expands on the possibilities of a gender-neutral language:

“When, as a poet, you are not limited by the restraints of writing of a certain gender, it opens up to new nuances in language. Not only is it liberating to the artist themselves to be able to write from numerous positions, but also the object is divorced from gender and can claim many parts, both relating to gender, but also relating to who is object and subject in the poem.”

Shadi Angelina Bazeghi is also familiar with the expanse of interpretative possibility in classical Iranian poetry. Sticking with tradition, she will sometimes crack open a random page in Hafez’s (1320-1390) poetry collection and read a “favorite.” According to folklore, Hafez will give the exact answer to any question posed.

“The poem often consists of two figures, a narrator and a recipient. And due to the gender-neutral nature of the language, it is difficult to discern who is subject and who is object. Multiple people are referred to with the pronoun ou, and it’s actually pretty nuts that I sometimes can’t discern if one or the other is a man or a woman. That’s the potentiality that language contains. Classic poets like Hafez and Rumi have also utilized it — there is an expansion of a poetic space where the task of “gendering” is on the reader, be it as a man, woman, queer or…”

According to Bazeghi, many poets whose poems can be interpreted as erotic, like Hafez and Rumi, switch up the relations between gender, physical versus spiritual being, and geographic-national senses of belonging.

“Rumi writes himself out of a gendered body that belongs to East or West, any religion or nation etc. Instead he defines himself as an un-gendered body that belongs to love, and is intoxicated, spiritually elevated, by love itself.”

“That might be one of the reasons why so many Iranians read poetry, regardless of gender. This is especially true of Forough Farrokhzad. Her poems can be read in different ways, and part of this stems from the gender-neutral language. This makes the content much more relatable to larger groups of people. How you, as a reader, are situated in the poem is not a given. Thus, all poetry becomes more engaging.”

“This is not to say that the language is completely devoid of gender,” Bazeghi notes. “For instance, ‘the lover,’ meaning the active part, has traditionally been male, whereas the ‘the beloved’ e.g. the passive, was female.”

But even in the dominantly gender-neutral language, Forough manages to experiment with these positions by using a traditionally female word for the obviously male object of desire. One could say that she’s queering up the heterosexual hierarchy, where roles are given based on a person’s assigned gender within a binary system, like women being passive and men being active. Forough doesn’t comply with that, but manages to challenge it boldly.

But how does one go about translating these lingual finesses?

“As a Danish translator, I have to make some choices. In Persian, the word for the beloved, ma’shough (معشوق) is oftentimes associated with ethereal love or the feminine, even if the word is technically gender-neutral — seeing as the word ma’shoughe (معشوقه) means female lover. Even so, Forough chooses to use the word ma’shoughe man (معشوق من) i.e. my beloved to speak of the object of the poem. She could easily have chosen a different word that is solely associated with the masculine.

Forough deliberately seeks to overhaul the traditional roles, and it is the male role in the erotic play that she wants to rattle, and by extension that of the female, which she clearly identifies with. At the same time she equalizes the carnal and the ethereal love, the latter having commonly been thought of as superior.”

In Danish, the word has become min elsker. In principle, this is a male lover in Danish, because there is a female equivalent with a feminine suffix. However, it can be viewed as somewhat neutral, like “my beloved” in English. Bazeghi has, because of the way she reads Farrokhzad, been forced to sometimes use gender specific pronouns.

“It is limiting to transition from a gender-neutral to a gendered language. This is not to say, however, that a neutral language solves all problems. Outside the sphere of poetry, people are still targets of harassment, sexism, and homophobia no matter if they live in a gender-neutral or gendered language speaking area. But in the literary realm the gender-neutral facilitates an inclusive community where lived experience can be shared across gender lines.”

“Some people refer to it as “playing with language”, but for me, it’s important to get across that to Forough, this certainly was not a game. It was an earnest experimental process concerning language and poetry, and an opposition to traditional norms and values – both inside and outside poetry, and she did that with tremendous costs to herself, personally.

***

I asked Shadi Angelina Bazeghi to re-translate the poem Connection, from Another Birth 1959-1963, with the English gender-neutral pronoun ze to give readers an idea of how it changes the expression.

Emma Holtens has translated the poem to English from the Danish version by Shadi Angelina Bazeghi:

Connection

The dark pupils, oh,

my plain lonesome Sufis

had lost their temper

in ze’s eyes ritual attraction

I saw ze billow across my body

Like a scorching reddish flame

Like the ripple of water

A quivering brimming cloud

A sky of the seasons’ heated breath

Ze stretches

Till infinity

Till the other side of life

I saw my material being

Dispersed

By the gust of ze’s hands

I saw that ze’s heart’s adrift resonance

Had enchanted my heart

The clock flew

The wind seized the curtain

I had embraced ze

In the glow of fire

I wanted to say something

But gaped

Ze’s eyelashes

Were like threads of silk

Motioned in the depth of dark

After a protracted desire

And a quiver, a fierce quiver as if into death,

Toward the end of my lost I

I saw my release

I saw my release

I saw my skin crack from the expanse of love

I saw my flaming substance

Melting so slowly

And currents, currents, currents

Into the moon, the moon that lingered by the depth, the restless

And fuzzy moon

Xx

We had cried in each other

We had, like the mad, endured

The fusing’s erratic moment in each other

No comments:

Post a Comment