|

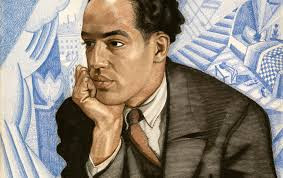

| Langston Hughes |

Langston Hughes

African-American poet, novelist, and playwright, who became one of the foremost interpreters of racial relationships in the United States. Influenced by the Bible, W. E. B. Du Bois, and Walt Whitman, Hughes depicted realistically the ordinary lives of black people. Many of his poems, written in rhythmical language, have been set to music. Hughes's poems were meant "to be read aloud, crooned, shouted and sung."

"Rest at pale evening...A tall slim tree...Night coming tendrerlyBlack like me.(from Dream Variations, 1926)

James Langston Hughes was born in Joplin, Missouri. His mother was a school teacher, she also wrote poetry. His father, James Nathaniel Hughes, was a storekeeper. He had wanted to become a lawyer, but he had been denied to take the bar exam. Hughes's parents separated and his mother moved from city to city in search of work.

In his rootless childhood, Hughes lived in Mexico, Topeka, Kansas, Colorado, Indiana and Buffalo. Part of his childhood Hughes lived with his grandmother. At the age of 13 he moved back with his mother and her second husband. Later the family settled in Cleveland, Ohio, where Hughes's stepfather worked in the steel mills. During this period Hughes found the poems of Carl Sandburg, whose unrhymed free verse influenced him deeply.

After graduating from a high school in Cleveland, Hughes spent a year in Mexico with his light-skinned father, who had found there a release as a successful cattle rancher from racism of the North. On the train, when he returned to the north, Hughes wrote one of his most famous poems, 'The Negro Speaks of Rivers.' It appeared in the African-American journal Crisis (1921). As an adolescent in Cleveland he participated in the activity of Karamu Players, and published in 1921 his first play, The Golden Piece.

Supported by his father, Hughes entered in the early 1920s the Columbia University, New York. For the disappointment of his family, Hughes soon abandoned his studies, and participated in more entertaining jazz and blues activities in nearby Harlem. Disgusted with life at the university and to see the world, he enlisted as a steward on a freighter bound to West Africa. He traveled to Paris, worked as a doorman and a bouncer of a night club, and continued to Italy.

After his return to the United States, Hughes worked in menial jobs and wrote poems, which earned him scholarship to Lincoln University in Pennsylvania. His first play, The Gold Piece (1921) was published in the children's magazine The Brownies' Book. According an anecdote, Hughes was "discovered" by the poet Vachel Lindsay in Washington. Lindsay was dining at the Wardman Park Hotel, where Hughes worked as a busboy, and dropped his poems beside the Lindsay's dinner plate. Lindsay included several of them in his poetry reading. It prompted interviews of the "busboy poet." Hughes quit his job and moved to New York City.

In 1929 Hughes received his bachelor's degree. He was celebrated as a young promising poet of the generation, publishing his poetry in Crisis (1923-24) and in Alain Locke's anthology The New Negro (1925). His first book of verse, The Weary Blues, supported by Carl Van Vechten, came out in 1926. "My news is this: that I handed The Weary Blues to Knopf yesterday with the proper incantations. I do not feel particularly dubious about the outcome: your poems are too beautiful to escape appreciation. I find they have a subtle haunting quality which lingers in the memory and an extraordinary sensitivity to all that is kind and lovely." (from Van Vechten's letter to Hughes in Remember me to Harlem, ed. by Emily Bernard, 2001)

Hughes valued Van Vechten's criticism and dedicated him his second collection of poetry, Fine Clothes to the Jew (1927). Their correspondence, which lasted until Van Vechten's death in 1964, was published in 2001. The Weary Blues assimilated techniques associated with the secular music with verse, while its content reflected the lives of African-Americans. "Drowning a drowsy syncopated tune, / Rocking back and forth to a mellow croon, / I heard a Negro play. / By the pale dull pallor of an old gas light / He did a lazy sway... / He did a lazy sway..." (from 'The Weary Blues,' the title poem of the collection)

Hughes was considered one of the leading voices in the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s Not Without Laughter (1930), his first novel, Hughes wrote with the financial support of Charlotte Mason, a wealthy white woman. The book had a cordial reception and Hughes bought a Ford. He toured the colleges of southern America as a teacher and poet.

Noteworthy, Hughes was one of the first black authors, who could support himself by his writings. In the 1930s Hughes traveled in the Soviet Union, Haiti, and Japan. During his visit in the Soviet Union, to write the English dialogue for a film about black American workers, he had also an affair with an Afro-Chinese ballerina, Sylvia Chen, whose father Eugene Chen had served as a secretary to Sun Yat-Sen, the founder of the Chinese republic and then worked as foreign minister of China. "He was such a jolly person and so natural," Sylvia recalled. "Langston had been a sailor and he walked like one; I remember him sloshing around in white corduroy pants in the middle of a Russian winter." While in Moscow, Hughes completed his translations of Vladimir Mayakovsky's poems 'Black and White' and 'Syphilis' with the help of the critic Lydia Filatova. He also met Boris Pasternak and translated some of his poems.

'Goodbye, Christ,' a poem written during his world tour, was attacked by a right-wing religious group in the 1940s. Although Hughes decided to repudiate the work publicly, he also embraced radical politics, publishing a collection of satiric short stories, The Ways of White Folks (1943), and returned to satire and racial prejudices later in Laughing to Keep from Crying (1952) and Something in Common (1963). Hughes emphasized the importance of African culture and shared Du Bois's belief that renewal could only come from an understanding of African roots.

"My old man died in a fine big house.My ma died in a shack.I wonder where I'm gonna die,Being neither white nor black?"(from 'Cross')

Hughes's play The Mulatto (1935) premiered in 1935 with great success on Broadway at the Vanderbilt Theatre. To maximize sex and violence in the drama, the producer Martin Jones had added a scene in which a white overseer rapes the hero's sister. Alterations were made without Hughes's knowledge, but the fact that his first professionally developed play had opened on Broadway made him feel less disappointed with the production. Moreover, the same year Hughes won a Guggenheim Fellowship, which gave him some financial security for a period of time.

During the Spanish Civil War (1937) Hughes served as a newspaper correspondent for the Baltimore Afro-American, reporting on the African American volunteers fighting for the Loyalists in the International Brigades. While in Madrid, he became a friend of Ernest Hemingway, with whom he attended bullfights. From circa 1942 onwards, Hughes made Harlem his permanent home, but continued lecturing at universities around the country.

Hughes wrote children's stories, non-fiction, and numerous works for the stage, including lyrics for Kurt Weill's and Elmer Rice's opera Street Scene, which opened at the Delphi Theatre on January 9, 1947, screenplay for the Hollywood film Way Down South with the actor Clarence Muse, and translated the poetry of Federico García Lorca and Gabriela Mistral. Hughes's Christmas play, Black Nativity, has been produced every year by major black theaters. Street Scene was Rice's drama of tenement life in the lower east side of Manhattan. Chicago Daily News compared the Broadway musical adaptation to the Gershwin classic Porgy and Bess. Hughes also founded black theatre groups in Harlem, Chicago, and Los Angeles.

When the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace was arranged in March 1949, at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York, Hughes was one of the attendees. The event gathered left-leaning American artists of all disciples to meet their Soviet counterparts. On the final night of the conference, Dmitri Shostakovich played a piano arrangement of the Scherzo of his Fifth Symphony at Madison Square Garden. Several days later Life magazine published a photo essay headlined "RED VISITORS CAUSE RUMPUS: DUPES AND FELLOW TRAVELERS DRESS UP COMMUNIST FRONTS," in which the attendees were said to be aiding the Communist cause. Hughes, who was a member-at-large of the National Council and one of the sponsors of the conference, appeared as a "fellow traveler" alongside Charles Chaplin, Aaron Copland, Albert Einstein, Lillian Hellman, Norman Mailer, Arthur Miller, Clifford Odets, Dorothy Parker, and a number of other delegates.

Hughes's inaccurate reputation for being a Communist dates from his poems in the 1930s. Lines from 'Goodbye, Christ' were presented as proof that he was a professed Communist: Goodbye, / Christ Jesus Lord God Jehovah, / Beat it on away from here now. / Make way for a new guy with no religion at all— / A real guy named / Marx Communist Lenin Peasant Stalin worker ME . . . ."In 1953, during the era of McCarthyism, Hughes tested to the Senate committee that he was not, and never had been, a Communist. He named no names, well aware of blacklisting and its effects on such radicals as Paul Robeson. In several of his poems, Hughes had expressed with ardent voice sociopolitical protests. He portrayed people, whose lives were impacted by racism and sexual conflicts, he wrote about southern violence, Harlem street life, poverty, prejudice, hunger, hopelessness. But basically he was a conscientious artist, kept his middle-of-the road stance and worked hard to chronicle the black American experience, contrasting the beauty of the soul with the oppressive circumstance.

"Wear itLike a bannerFor the proud –Not like a shroud."(from Color, 1943)

In the 1950s Hughes published among others Montage of a Dream Deferred (1951), which included his famous poem 'Harlem,' A Pictorial History of the Negro in America (1956), and edited The Book of Negro Folklore (1958) with Arna Bontemps. Hughes's autobiographicals books include The Big Sea (1940) and I Wonder as I Wander (1956). For juveniles he did a series of biographies, beginning with Famous American Negroes (1954). His popular comic character Jesse B. Semple, or "Simple," appeared in columns for the Chicago Defender and the New York Post. Hughes had met the prototype of the character in a bar. The ironic comments of the street-wise Harlem dweller were first collected into Simple Speaks His Mind (1950). In the last Simple collection, Simple's Uncle Sam (1965), Hughes wrote: "My mama should have named me Job instead of Jesse B. Semple. I have been underfed, underpaid, undernourished, and everything but undertaken – yet I am still here. The only thing I am afraid of now – is that I will die before my time."

In his later years Hughes held posts at the Universities of Chicago and Atlanta. The poet also witnessed that doctoral dissertations already begun to be written about him – the earliest book on his work appeared already in the 1930s. At a White House lunch in 1961, hosted by President John F. Kennedy in honor of Leopold Sédar Senghor, the poet and president of Senegal specially mentioned Hughes as a major early source of inspiration. A Tennessee newspaper spoke about his presence in the White House as "an affront to every man and woman in this country, of all creeds." Hughes, with his gift of good humour, was an excellent dinner guest. Once when he sat next to the bored Carson McCullers, they had fun translating the French menu into jive English.

Hughes never married and there has been unrelevant speculations about his sexuality. Several of his friends were homosexual, among them Carl Van Vechten, who wrote the controversial novel Nigger Heaven (1926) – Hughes had recommended the choice of the title – but several were not. When the actress and playwright Elsie Roxborough had proposed Hughes in 1936, he pleaded poverty as his reason for bachelorhood. After black papers began to report that they were about to marry, Hughes stated in the Baltimore Afro-American, that "I am a professional poet and while poetry is so frequently associated with romance, there seems to be little compatibility between poetry and marriage, especially where one must depend on it to support a wife."

Langston Hughes died in Polyclinic Hospital in New York, on May 22, 1967, of complications after surgery. His collection of political poems, The Panther and the Lash (1967), reflected the anger and militancy of the 1960s. The book had been rejected first by Knopf in 1964 as too risky. Hughes's own history of NAACP came out in 1962; he had received a few year's earlier the NAACP'S Spingarn Medal.

Hughes published more than 35 books, he was a versatile writer, but he hated "long novels, narrative poems," as he once said. Although the Harlem Renaissance faded away during the Great Depression, its influence is seen in the writings of later authors, such as James Baldwin, who, however, criticized Hughes's poetic achievement. From the late 1940's through the 1950's Hughes revised under pressure his poems – many of them became less tough.

For further reading: To Make a Black Poet by S. Redding (1939); Langston Hughes by J. Emanuel (1967); Black Genius: A Critical Evaluation, ed. by T. O'Daniel (1971); A Biobibliography of Langston Hughes 1902-1967 by D.C. Dickinson (1972); Langston Hughes: The Poet and His Critics by R.K. Barksdale (1977); The Life of Langston Hughes: 1902-1941: I, Too, Sing America by Arnold Rampersad (1986); The Life of Langston Hughes, 1941-1967: I Dream a World by Arnold Rampersad (1988); The Art and Imagination of Langston Hughes by R. Baxter Miller (1990); Langston Hughes: Critical Perspectives Past and Present, ed. by Henry Louis Gates (1993); Langston Hughes: A Study of the Short Fiction by Hans Ostrom (1993); Coming Home: From the Life of Langston Hughes by Floyd Cooper (1994; note: for ages 4-8); Free to Dream by Audrey Osofsky (1996; note: for ages 9-12); Langston Hughes by Joseph McLaren et al. (1997); Langston Hughes: Poet of the Harlem Renaissance by Christine M. Hill (1997); Langston Hughes: Comprehensive Reserach and Study Guide, ed. by Harold Bloom (1999); Remember me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, 1925-1964, edited by Emily Bernard (2001); The Life of Langston Hughes: Volume I: 1902-1941, I, Too, Sing America by Arnold Rampersad (2002); The Life of Langston Hughes: Volume II: 1914-1967, I Dream a World by Arnold Rampersad (2002); Langston Hughes and American Lynching Culture by W. Jason Miller (2010); Langston Hughes, edited by R. Baxter Miller (2013); Race in the Poetry of Langston Hughes, edited by Claudia Durst Johnson (2014); Red Modernism: American Poetry and the Spirit of Communism by Mark Steven (2017) - See also: Countee Cullen. Harlem literature: (novels) Jean Toomer's experimental Cane (1923), Claude McKay's Home to Harlem (1928); Countee Cullen's One Way to Heaven (1932), Anna Bontemps's Black Thunder (1936); (poems and plays) Abraham Hill's On Striver's Row (1933), Langston Hughes's Shakespeare in Harlem (1942). Harlem Renaissance, see This Was Harlem by Jervase Anderson (1981), Modernism and the Harlem Renaissance by Houston A. Baker Jr (1987). Note 1: Hughes's 'The Negro Speaks of Rivers,' written on a train taking him to Mexico, has been among the most quoted of all poems by black poets. Note 2: According to the Kansas poet Eric McHenry, Hughes was born a year earlier than generally assumed. (The Guardian, 10 Aug 2018)

Selected works:

- The Negro Speaks of Rivers, 1921 (poem published in the journal Crisis)

- The Gold Piece, 1921 (play; publ. in The Brownies' Book)

- The Weary Blues, 1926 (incl. the poem Dream Variation; with an introduction by Carl Van Vechten, 1929)

- Fine Clothes to the Jew, 1927

- Not Without Laughter, 1930

- Dear Lovely Death, 1931

- The Negro Mother, and Other Dramatic Recitations, 1931 (with decorations by Prentiss Taylor)

- Mule Bone, 1931 (with Zora Neale Hurston)

- Dear Lovely Death, 1931

- The Dream Keeper and Other Poems, 1932 (with illustrations by Helen Sewell)

- Scottsboro Limited: Four Poems and a Play in Verse, 1932 (with illustrations by Prentiss Taylor)

- Popo and Fifina, Children of Haiti, 1932 (with Arna Bontemps, illustrations by E. Simms Campbell)

- The Ways of White Folks, 1934

- Little Ham, 1935 (play)

- The Mulatto, 1935 (play)

- Emperor of Haiti, 1936 (play)

- Troubled Island, 1936 (play, with William Grant Still)

- When the Jack Hollers, 1936 (play)

- Front Porch, 1937 (play)

- Joy to My Soul, 1937 (play)

- Soul Gone Home, 1937 (play)

- Don't You Want to be Free?, 1938 (play)

- A New Song, 1938 (introd. by Michael Gold; frontispiece by Joe Jones)

- The Em-Fuehrer Jones, 1938 (play)

- Limitations of Life, 1938 (play)

- Little Eva's End, 1938 (play)

- The Organizer, 1939 (musical play, with James P. Johnson)

- The Big Sea: An Autobiography, 1940

- Shakespeare in Harlem, 1941 (with drawings by E. McKnight Kauffer)

- The Sun Do Move, 1942 (play)

- Way Down South, 1942 (screenplay)

- For This We Fight, 1943 (play)

- Freedom's Plow, 1943

- Jim Crow's Last Stand, 1943

- Laments for Dark Peoples, 1944

- Street Scene, 1946 (musical; lyrics by Langston Hughes, music by Kurt Weill, based on a book by Elmer Rice)

- Fields of Wonder, 1947

- Masters of Dew / Jacques Roumain, 1947 (translator, with M. Cook)

- Cuba Libre / Nicholas Guillen, 1948 (translator, with F. Carruthers)

- One-Way Ticket, 1949 (illustrated by Jacob Lawrence)

- The Poetry of the Negro, 1949 (ed.)

- Simple Speaks His Mind, 1950

- The Barries, 1950 (play)

- Montage of a Dream Deferred, 1951 (incl. poem Harlem)

- Laughing to Keep from Crying, 1952

- The First Book of Negroes, 1952 (pictures by Ursula Koering)

- Simple Takes a Wife, 1953

- Famous American Negroes, 1954

- The First Book of Rhythms, 1954 (pictures by Robin King)

- Famous Negro Music Makers, 1955

- The First Book of Jazz, 1955 (pictures by Cliff Roberts, music selected by David Martin)

- Sweet Flypaper of Life, 1955 (photographs by Roy DeCarava)

- I Wonder as I Wander: An Autobiographical Journey, 1956

- The First Book of the West Indies, 1956 (pictures by Robert Bruce)

- A Pictorial History of the Negro in America, 1956 (with Milton Meltzer)

- Selected Poems of Gabriel Mistral, 1957 (translator)

- Simple Takes a Claim, 1957

- Simply Heavenly, 1957 (play)

- Tambourines to Glory: A Novel, 1958

- Famous Negro Heroes of America, 1958 (illustrated by Gerald McCann)

- The Book of Negro Folklore, 1958 (ed. with Arna Bontemps)

- The Langston Hughes Reader, 1958

- Selected Poems, 1959 (drawings by E. McKnight Kauffer)

- The First Book of Africa, 1960

- The Best of Simple, 1961 (illustrated by Bernhard Nast)

- Ask Your Mama, 1961

- The Prodigal Son: A Gospel Song-Play, 1961

- Black Nativity, 1961 (play)

- Gospel Glory, 1962

- Fight for Freedom: The Story of the NAACP, 1962

- Five Plays, 1963 (plays, edited with an introd. by Webster Smalley)

- Jericho-Jim-Crow-Jericho: A Song-Play, 1963

- Something in Common, and Other Stories, 1963

- New Negro poets, U.S.A., 1964 (edited by Langston Hughes, foreword by Gwendolyn Brooks)

- Simple's Uncle Sam, 1965

- Soul Yesterday and Today, 1965 (play)

- The Book of Negro Humor, 1966 (selected and edited by Langston Hughes)

- Angelo Herdnon-Jones, 1966 (play)

- Mother and Child, 1966 (play)

- Outshines the Sun, 1966 (play)

- Trouble with Angels, 1966 (play)

- The Panther and the Lash: Poems of Our Times, 1967

- The Best Short Stories by Negro Writers: An Anthology from 1899 to the Present, 1967 (ed.)

- Black Magic: A Pictorial History of the Negro in American Entertainment, 1967 (with Milton Meltzer)

- Black Misery, 1969 (illus. by Arouni)

- Three Negro Plays, 1969 (with an introduction by C. W. E. Bigsby)

- Don’t You Turn Back: Poems, 1969 (selected by Lee Bennett Hopkins, woodcuts by Ann Grifalconi)

- Good Morning Revolution: Uncollected Social Protest Writings, 1973 (edited and with an introd. by Faith Berry, foreword by Saunders Redding)

- Langston Hughes in the Hispanic World and Haiti, 1977 (edited by Edward J. Mullen)

- Jazz, 1982 (3rd ed., updated and expanded by Sandford Brown)

- Arna Bontemps-Langston Hughes Letters, 1925-1967, 1990 (selected and edited by Charles H. Nichols)

- The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes, 1994 (edited by Arnold Rampersad)

- The Return of Simple, 1994 (edited by Akiba Sullivan Harper, introduction by Arnold Rampersad)

- Langston Hughes and the Chicago Defender: Essays on Race, Politics, and Culture, 1942-62, 1995 (edited by Christopher C. De Santis)

- Short stories, 1996 (edited by Akiba Sullivan Harper, with an introduction by Arnold Rampersad)

- The Pasteboard Bandit, 1997 (illustrated by Peggy Turley)

- Carol of the Brown King: Nativity Poems, 1998 (illustrated by Ashley Bryan)

- Sunrise Is Coming after While, 1998 (poems selected by Maya Angelou, silkscreens by Phoebe Beasley)

- Poems, 1999 (selected and edited by David Roessel)

- The Political Plays of Langston Hughes, 2000 (with introductions and analyses by Susan Duffy)

- Remember Me to Harlem: The Letters of Langston Hughes and Carl Van Vechten, 1925-1964, 2001 (edited by Emily Bernard)

- Collected Works of Langston Hughes, 2001-2004 (v. 1-6, 8-16, edited with an introduction by Arnold Rampersad)

- Let America be America again and Other Poems, 2004 (preface by John Kerry)

- My People, 2009 (photographs by Charles R. Smith Jr.)

- Langston Hughes and the South African Drum Generation: The Correspondence, 2010 (edited by Shane Graham and John Walters, introduction by Shane Graham)

- I, too, Am America, 2012 (illustrated by Bryan Collier)

- Selected Letters of Langston Hughes Hardcover, 2015 (edited by Arnold Rampersad, David Roessel, Christa Fratantoro)

- Letters from Langston: From the Harlem Renaissance to the Red Scare and Beyond, 2016 (edited by Evelyn Louise Crawford and MaryLouise Patterson; with a foreword by Robin D.G. Kelley)