|

| Lawrence Ferlinghetti |

A LIFE IN POETRY

Lawrence Ferlinghetti: ‘Most of the poets were on something, but somebody had to mind the shop’

The publisher of the Beats talks about Ginsberg the showman, the Albert hall ‘happening’ and how one of his own poets emptied the City Lights till

Colin Robinson

4 July 2015

B

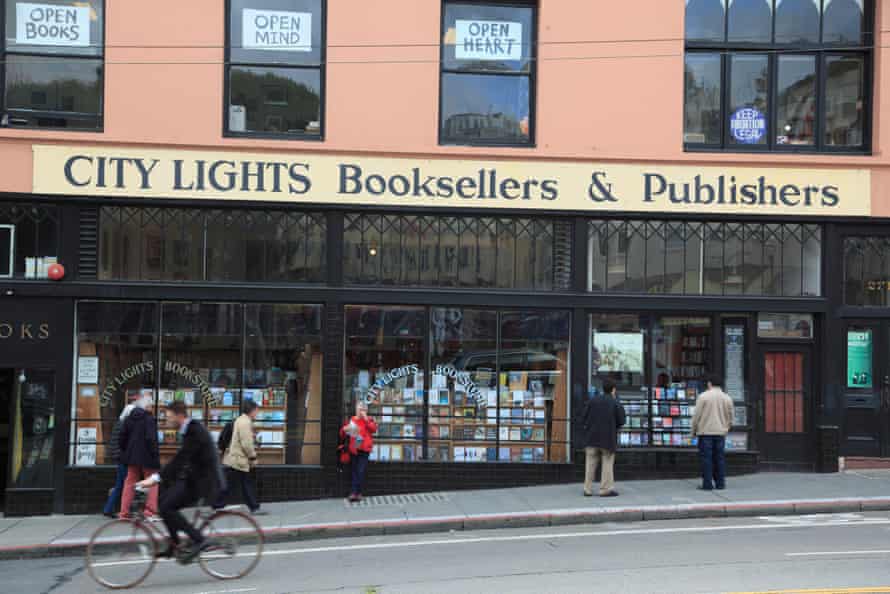

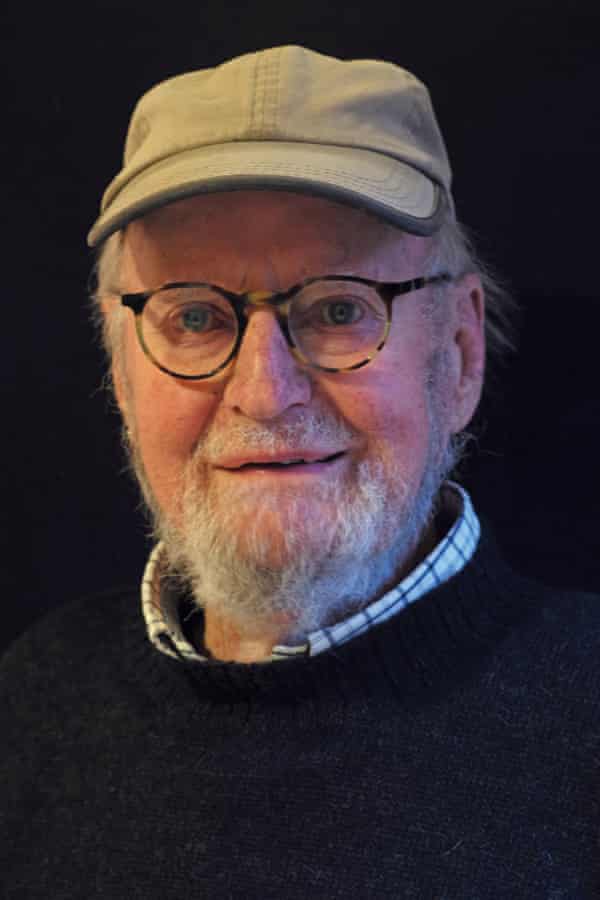

He directs me upstairs to the kitchen of his second floor apartment, past a scrappy unframed poster of Vladimir Mayakovsky taped roughly to the wall. “It’s a real Italian building,” he says. “The kitchen is the entire width of the house.” Ferlinghetti has lived here, on his own, for more than 30 years. I’m here to talk to him about a confluence of significant events: the 60th anniversary of the company he founded, City Lights, publishers of a celebrated poetry list that includes Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” and an extensive range of titles in radical politics and offbeat fiction; the appearance later this year of a collection of his correspondence with Ginsberg, and a compilation of his own travel writings; and another anniversary, that of the International Poetry Incarnation, held in the Albert Hall in London 50 years ago this summer. There, followed by Beat poets Ginsberg and Gregory Corso, he read to an audience of 7,000 at an event billed as Britain’s first “happening”.

We begin with the Albert Hall event. I point out that, on the evidence of Peter Whitehead’s darkly atmospheric film of the proceedings, Wholly Communion, the crowd seemed pretty stoned that night. The readings were interrupted at one point by a young man mesmerically chanting the word “love” at the top of his voice. “It wasn’t just the audience,” Ferlinghetti chuckles, “most of the poets were on something, either just grass, more likely LSD … But I was totally straight. I was probably the only straight man on stage.”

He appears to relish his reputation as the abstemious one. “Somebody had to mind the shop,” he tells me, enjoying the literalism (City Lights is also a world-famous bookstore). Everything is relative, however: compared to Ginsberg, who rarely encountered a drug he didn’t want more of, or Jack Kerouac, who was notorious for drinking heavily with his mother in the house they shared, Ferlinghetti seems a paragon of restraint. But in his travel writing from Andalucia, where he lived in the spring before the Albert Hall gig, he is regularly on the lookout for “kif” and, on one occasion, recounts being so drunk that he tumbled into a patch of tomatoes in the garden, where he lay unconscious until his wife found him.

If Ferlinghetti’s sobriety was only relative, it extended to the use of swear words. Though the poem with which he opened at the Albert Hall was titled “To Fuck Is to Love Again”, he is quick to point out that it’s “the only poem of mine which had a four-letter word in it. Generally, dirty words divert the attention from what you’re trying to get across.”

I suggest that the performances of the American poets that night – himself, Ginsberg and Corso – looked more self-assured than those of their British counterparts, among them Christopher Logue, Adrian Mitchell, Tom McGrath and Michael Horovitz. “The thing about the British poets was that though they looked like Beats, when they opened their mouths, out came these beautiful Oxford accents. It sort of destroyed the image.” So were the Beats in America more working class? “Gregory certainly was, he had a strong New York accent. Allen was from Jewish intellectuals in Newark who were old communists and identified with the workers’ movement.”

Given those family politics it seems an irony that Ginsberg arrived in London having been expelled from communist-run Czechoslovakia. The authorities there had taken possession of a notebook that, according to its owner, included “descriptions of sex orgies and ecstasies in intimate detail”. Ferlinghetti smiles and removes his glasses to dab eyes now afflicted with glaucoma: “Well, Allen made the most of being kicked out of Prague. He was leaving anyway. Besides being a genius poet, he was a master publicist and showman.”

Anyway, the communists, the official ones at least, had little truck with the Beats. “The Russian poet Andrei Voznesensky was at the Albert Hall but the Soviet embassy wouldn’t let him read. They didn’t want him to associate with dirty beatniks. He was on the front row but the audience didn’t even know he was there.”

Voznesensky was a recent friend. “The following year we appeared together in San Francisco. I set up a big a reading for him, just as we’d done with Yevtushenko.” The event is described in Ferlinghetti’s travel journals. It took place at the Fillmore, the cavernous music venue run by Bill Graham. The plan was to follow the poetry with a live band but Voznesensky objected: “When he first got a look at the hand bill he called me up … ‘Lawrence, what is Jefferson Airplane?’ [After] I told him it was a rock group … he said ‘Lawrence, just you and me. No Airplane.’” Persuaded later to change his mind, Ferlinghetti records, the Russian watched the band from the balcony, sitting with the man running the light show. “He did dig it, after all.”

Ferlinghetti included Voznesensky in City Lights’ anthology of Eastern European poets Red Cats (title courtesy of Ginsberg) and the conversation turns to his role as a publisher. I suggest that his correspondence with Ginsberg traces a relationship drifting gradually from the informality of friends to something much more businesslike, as the two men established their respective careers. Ferlinghetti demurs. “It’s true we had no contracts, including for ‘Howl’. But Allen never really included me in his inner circle. I wasn’t one of his in-group. I was always his publisher.”

Ferlinghetti became aware of the power of Ginsberg’s most famous poem when, alongside a boisterous Kerouac, he heard “Howl” read for the first time at the Six Gallery in North Beach during October 1955. The next day he sent a telegram to Ginsberg, who was living nearby at the time: I GREET YOU AT THE BEGINNING OF A GREAT CAREER. STOP. WHEN DO I GET MANUSCRIPT OF HOWL? The poem was soon on the presses at Villiers Publications in Britain, contracted by Ferlinghetti because their production was superior to anything available in the US: “The first printings were handset in old-fashioned type and thread sewn. John Sankey, who owned the press, had a very expensive sports car, a Jaguar. He drove me up to his factory an hour north of London at enormously high speed.”

The books were shipped to America through San Francisco. On arrival, the customs announced they would be seized for obscenity. They were eventually let through, but not without repercussions: “In the end it was the juvenile department of the police who charged us. I was in Big Sur at the time, and Allen was in Morocco. But our bookstore manager was dragged off to jail.”

The subsequent trial lasted months. Ginsberg, writing from Tangier where, between hanging out with Francis Bacon and Paul Bowles, he was assisting William Burroughs with the editing of Naked Lunch, was evidently concerned about its outcome. Characteristically, though, he struck a defiant note: “I guess this is more serious than the customs seizure … I’m really sorry I’m not there ... I never thought I’d want to read “Howl” again but it would be a pleasure under these circumstances. It might give it a reality as ‘social protest’ I always feared was lacking without armed bands of outraged Gestapo.”

Ferlinghetti remained sanguine and, like any good publisher, saw opportunity alongside the risk. “I wasn’t worried. I was young and foolish. I figured I’d get a lot of reading done in jail and they wouldn’t keep me in there for ever. And, anyway, it really put the book on the map.” He had sent the poem to the American Civil Liberties Union prior to publishing it “to see if they would defend us if we were busted. And they did – successfully as it turned out.” The not-guilty verdict heralded a new freedom in American letters. “After that the floodgates were opened. People like Barney” – Barney Rosset at Grove Press – “were able to publish Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Henry Miller’s Tropics, Jean Genet, and so on.”

The trial also launched Ginsberg’s career on a meteoric trajectory. The letters chronicle an increasingly confident young poet, never backward at coming forward, placing ever greater demands on his publisher, not least the repeated insistence that a variety of acquaintances be added to the City Lights list. “It seemed like half the people Allen recommended were current or ex-boyfriends. Some of them would never have gotten published if it hadn’t been for him.” In fact, Ferlinghetti remained coolly impervious when Ginsberg’s entreaties didn’t accord with his own interests and tastes. In declining to take on Naked Lunch he wrote to Ginsberg and Burroughs, then living together in Paris: “Anyone that published it as is would be indulging in pure and sure premeditated legal lunacy.” According to Paul Yamazaki, who has been the buyer for City Lights bookstore for more than four decades, this is just part of the story. “Lawrence didn’t care much for Burroughs’s writing until Soft Machine came out a couple of years later.”

As the publisher at City Lights, dealing with pushy and sometimes outrageously obstreperous writers went with the territory. Another of his poets, Corso, once broke into the bookshop and emptied the till. Ferlinghetti relates the events of that night: “The people in the Vesuvio bar next door saw him do it. We had a policy at City Lights never to call the police. We even had a sign up that said: ‘We will not call the police for book thieves. But they may be publicly shamed.’ Our bookstore manager once literally took down a guy’s pants to retrieve some stolen books.” But, in Corso’s case, it was the bar that summoned the cops, who arrived and dusted the till for fingerprints. “When we heard about it we went round to Gregory’s house. It was three in the morning. We told him the police had his number and he better get out of town. He left immediately for Italy. Didn’t return for two years.” Did Ferlinghetti ever retrieve the stolen money? “Well, we just took it out of his royalties. It seemed like the civilised thing to do.”

I’ve been advised prior to the interview that Ferlinghetti is essentially a private person, something that can easily be mistaken for aloofness. This characteristic is simultaneously underscored and belied by the direct way he brings our conversation to a close. “You seem to have quite a lot now,” he says, gesturing to my tape recorder, “and I want to watch the Giants game.”

Before leaving I ask if he is working on anything. He says he is collaborating with an Italian journalist who lives locally on the translation of a book by the poet Carmelo Bene. “We hope to have it finished within a year or two.” And does he go into City Lights these days? “Not really. Elaine [Katzenberger] is running things there. She’s an excellent editor – tough, and sometimes very funny. And it’s harder for me to get about now. I was just invited to a poetry reading in Norway but had to turn it down. Such a shame,” he adds ruefully, “they were going to pay business class. Do you know how rare it is for a poet to get business class?”

THE GUARDIAN

No comments:

Post a Comment