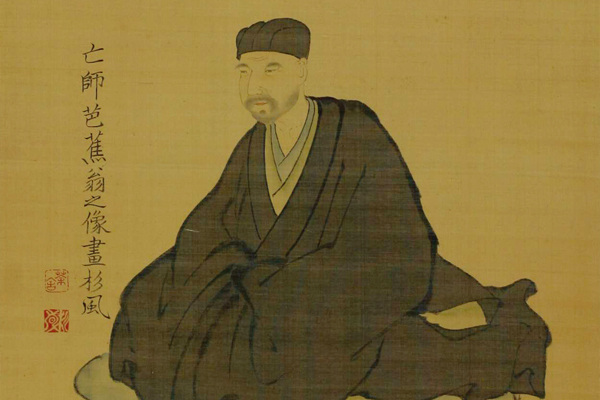

1644〜1694

松尾 芭蕉 Matsuo Bashō

An Artist Who Summarized the Beauty of Japan in Haiku While on a Life-Risking Journey

9 August 2023

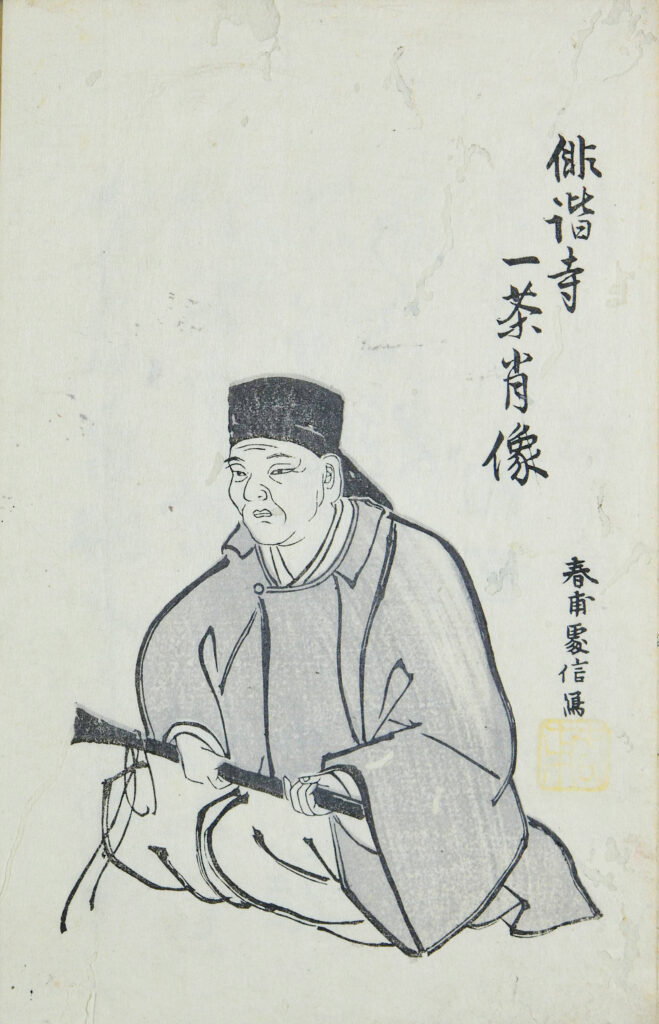

Do you know someone who is famous for haiku? In Japan, there are several people that are famous for their haiku. Among them, Matsuo Basho, who was active in the Edo period (1603-1867), is known worldwide for developing haikai, the original form of haiku.

In this article, we will introduce who Matsuo Basho was and what his masterpiece “Oku no Hosomichi” (The Narrow Road to the Interior) is all about.

The Life of Matsuo Basho

Matsuo Basho was a man of the early Edo period who perfected the art of haikai, from which haiku is derived. His name “Basho” was his haiku pen name he made around 1680, and his real name was Munefusa Matsuo.

He was born in 1644 into a farming family in Iga Province (present-day Mie Prefecture). His father, Matsuo Yozaemon, was reportedly a prominent figure in the area. However, his father died when he was 13 years old, and since he had many siblings, it must have been quite difficult.

In 1662, at the age of 18, he began to serve Yoshitada Todo, a member of the Todo family that ruled Iga Province, and aspired to find employment. In his late teens, he began to study haikai with Yoshitada under Kigin Kitamura, a haiku poet who was famous at the time.

In 1666, at the age of 22, he left the Todo family when his lord Yoshitada died. Due to losing all of his opportunities to be employed, he decided to pursue the path of haiku in earnest. In 1674, at the age of 30, he was recognized by Kigin Kitamura for his haiku skills, and so he left his side to become independent. Today, haiku has a traditional image, but at that time, it was still a new literary art form. So he decided to live as an artist of a new genre.

During his twenties, he was based in his hometown, and at the age of 32, he decided to move to Edo and set up his base of operations in the Nihonbashi area. However, being famous in Edo was not so easy. He could not make a living only by making haiku, and he also worked part-time as a civil engineer on the Kanda River. He interacted with many haiku poets and published many works while teaching haiku to samurai and merchants in Edo. He began to make a living by proofreading and editing the haiku they made.

At the age of 37, Basho suddenly moved his base to Fukagawa. While Nihonbashi was at the center of Edo, Fukagawa was on the east side of the Sumida River, an area that was originally the sea but was reclaimed and turned into residential land, so it was quite far from the center of Edo. It was a frontier area with a lot of untouched nature that was not very accessible. It seems that he moved there in search of a new place to free himself from the hassles of corrections and human relations to earn a living and create an environment where he could concentrate on his own creative activities.

Incidentally, the name “Basho” also comes from the fact that when he set up his hermitage in Fukagawa, his disciple sent him a Basho plant, which he planted in his garden. After this, he traveled all over Japan to write haiku and established Basho’s haiku style called “Shofu”, and became a highly accomplished artist.

Then, at the age of 46, he embarked on the so-called “Oku no Hosomichi” journey. This journey resulted in the composition of many of Basho’s masterpieces. He also succeeded in acquiring many disciples in the places he visited.

And he died at the age of 51. It is said that more than 300 of his disciples attended his funeral.

Was He a Spy?

A chronology of Matsuo Basho’s life reveals that he traveled much more than just the “Oku no Hosomichi”, and instead walked about 40 to 50 kilometers in a single day.

This has led some to speculate that Matsuo Basho may have been a spy for the Edo Shogunate, keeping an eye on the feudal lords in various regions. Since the journey along the “Oku no Hosomichi” was a strenuous one, covering 2,400 kilometers (miles) in approximately 150 days, there were assumptions made that Basho’s purpose in traveling was not simply to be an artist, but also to engage in covert activities.

At that time, there were many customs checkpoints in various places, and yet Basho was able to come and go there smoothly and managed to finance his 150-day journey. So we can think that there must have been some special exemption to solve the suspicion.

There is a precedent of lawyers and other artists having been engaged in espionage activities while visiting various countries under the guise of creative activities even before the Edo period, so it is not unlikely that Basho may have been a spy as well. Iga is also famous as a village of ninjas, but just because it is a place of secrecy does not mean that he was a ninja, as he was engaged in clandestine information-gathering activities. And whatever the backstory, there is no doubt that “Oku no Hosomichi” is a masterpiece of travel writing in Japanese history.

He was an avant-garde artist who constantly sought out new places and fresh scenery to create new expressions. Among his haiku, the most famous one is known to be the haiku about frogs, “Furuike ya/ Kawazu tobikomu/ Mizu no oto” (The old pond. A frog leaps in. Sound of the water).

The “Oku no Hosomichi” contains many of the haiku that Basho and his disciple, Sora Kawai, wrote during their travels throughout Japan. The “Oku no Hosomichi” is Matsuo Basho’s masterpiece, but what exactly was it about? The “Oku no Hosomichi” is a genre of travelogue that describes the actual itinerary of a journey. It mainly travels from the Tohoku region to the Hokuriku region, including present-day Toyama and Ishikawa prefectures, and includes haiku written by Matsuo Basho at each location.

About His Masterpiece: “Oku no Hosomichi”

The first part describes the background and motivation of why he decided to travel. In a nutshell, he says, “Travel is the best thing ever.”

Basho’s trip to the “Oku no Hosomichi” was made in the year of the 500th anniversary of the death of the famous poet Saigyo. So it is thought to be that it was a pilgrimage to a sacred place for him as well. It is also said that the impressive opening sentences of the “Oku no Hosomichi” were influenced by a poem by a Chinese poet named Li Bai. His pen name before he called himself Basho was “Momo Qing.” The meaning of this name is “blue peach” which is a peach that is still immature, implying he is not up to Li Bai. There is a respect that transcends time and borders.

From the town of Edo where Basho lived, he had a clear view of Mt. Fuji. An ukiyoe series, called Fugaku Sanjūrokkei (Thirty-six Views of Mt. Fuji) by Katsushika Hokusai, is a collection of 36 iconic paintings of Mt. Fuji drawn from the Mannen Bridge at Fukagawa, which is just around where Basho lived. These ukiyoe painted about 150 years after Basho’s trip depict how well you can see Mt. Fuji. From Tokyo today, you cannot see Mt. Fuji unless you climb a tall building, perhaps when the weather is nice. Basho wrote in his introductory paragraph that when he set out on his journey, he felt a bit anxious that he would not be able to see Mt. Fuji for a while.

Basho spoke then that he did not know if he would make it back to Edo alive, for traveling in those days was risking his life. It was in 1689, in the early Edo period when Matsuo Basho set out on his journey along the “Oku no Hosomichi.” It was only in the late Edo period (1603-1867), when the peace of the country was firmly established, that ordinary people were able to make journeys such as the famous Tokaidochu Hizakurige(Foot Travelers along the Tokai-do Road) by Ikku JUPPENSHA.

The route of the journey, the Oshu Kaido, was just being developed. At that time, there were very few inns for ordinary travelers, as the road was basically for samurai on their way to the capital. In fact, if you read “Oku no Hosomichi”, you will find that he stayed not only in inns but also in private homes, temples, and mountain huts, and he also left a poem phrase “Nomi Shirami / Uma no Shito Suru / Makura Moto (Fleas, lice, a horse peeing near my pillow).” It is quite harsh, isn’t it? Of course, he had to carry all his own luggage and walk dozens of kilometers a day, so there were possibilities that he fell ill and died during the journey, and there was also the danger of being killed by bandits who were after the travelers.

So, since he might not be able to come back, all of his close friends gathered together the night before and shared their farewells on the morning of his departure. They saw him off until they could no longer see his back.

When you know that the “Oku-no-Hosomichi” was a journey to prepare for death, the interpretation of the journey might change.

JAPAN UP MAGAZINE