Pablo Neruda’s Extraordinary Life, in an Illustrated Love Letter to Language

BY MARIA POPOVA

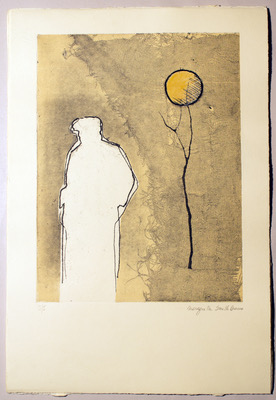

Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda (July 12, 1904–September 23, 1973) was not only one of the greatest poets in human history, but also a man of extraordinary insight into the human spirit — take, for instance, his remarkable reflection on what a childhood encounter taught him about why we make art, quite possibly the most beautiful metaphor for the creative impulse ever committed to paper.

Nobel laureate Pablo Neruda (July 12, 1904–September 23, 1973) was not only one of the greatest poets in human history, but also a man of extraordinary insight into the human spirit — take, for instance, his remarkable reflection on what a childhood encounter taught him about why we make art, quite possibly the most beautiful metaphor for the creative impulse ever committed to paper.

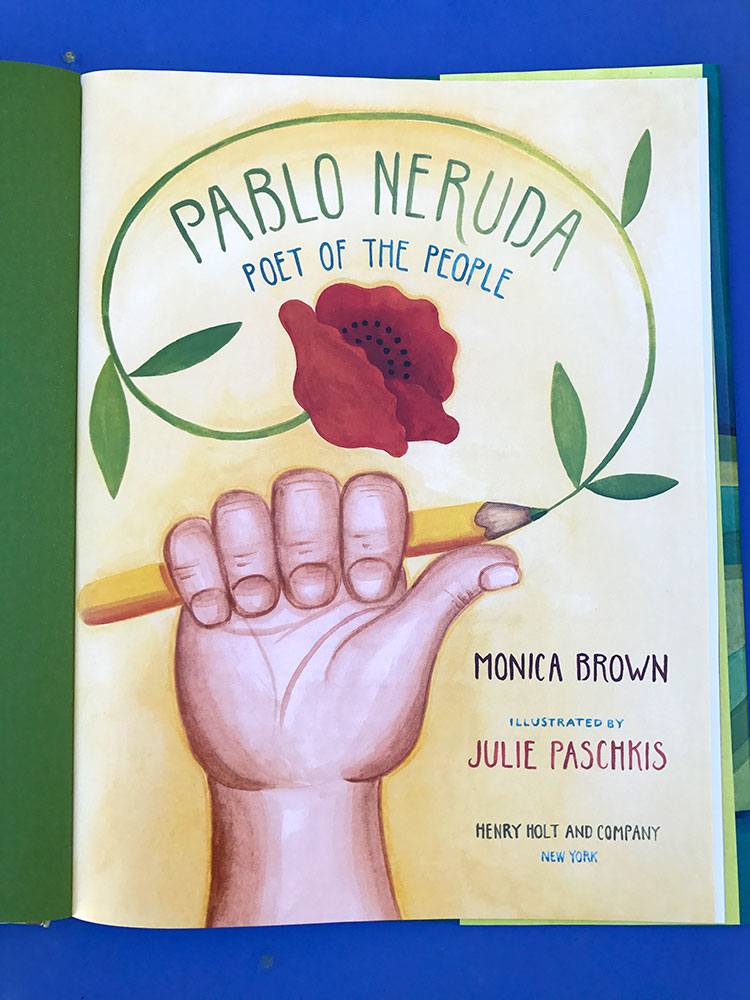

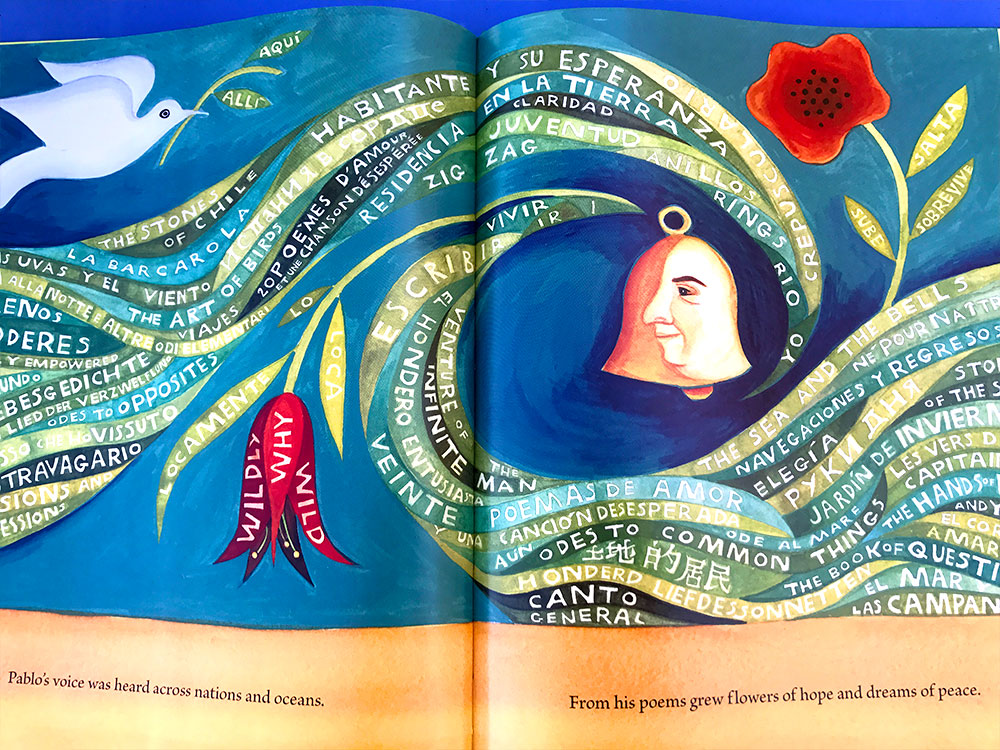

As a lover both of Neruda’s enduring genius and of intelligent children’s books, especially ones celebrating the lives of luminaries — such as the wonderful illustrated life-stories of Albert Einstein and Julia Child— I was instantly smitten with Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People (public library) by Monica Brown, with absolutely stunning illustrations and hand-lettering by artist Julie Paschkis.

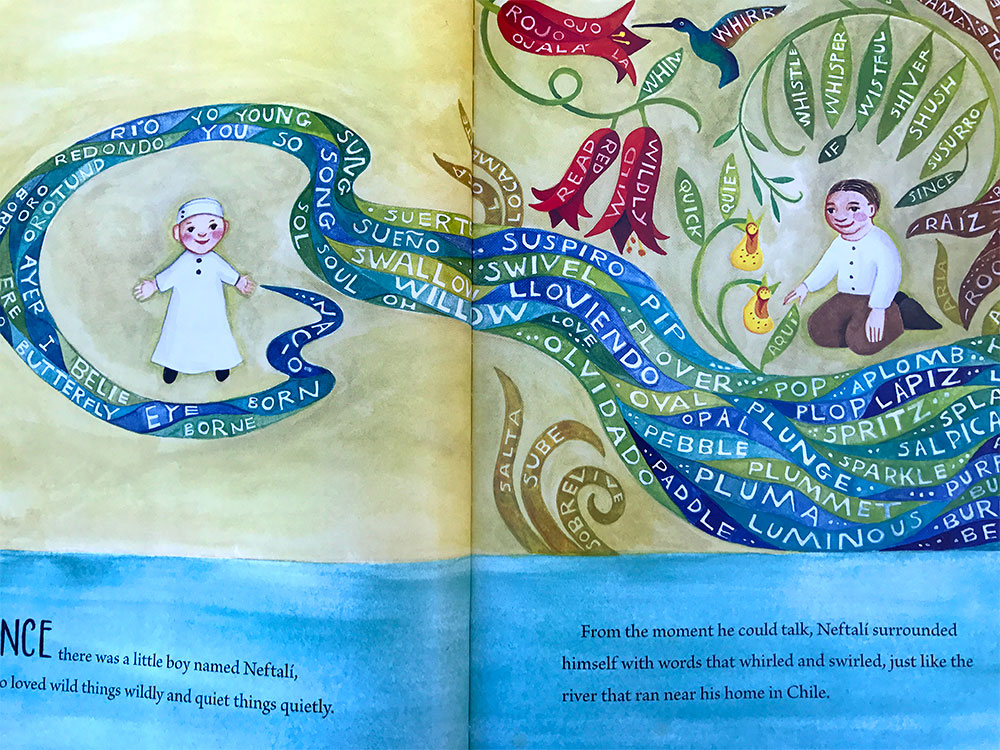

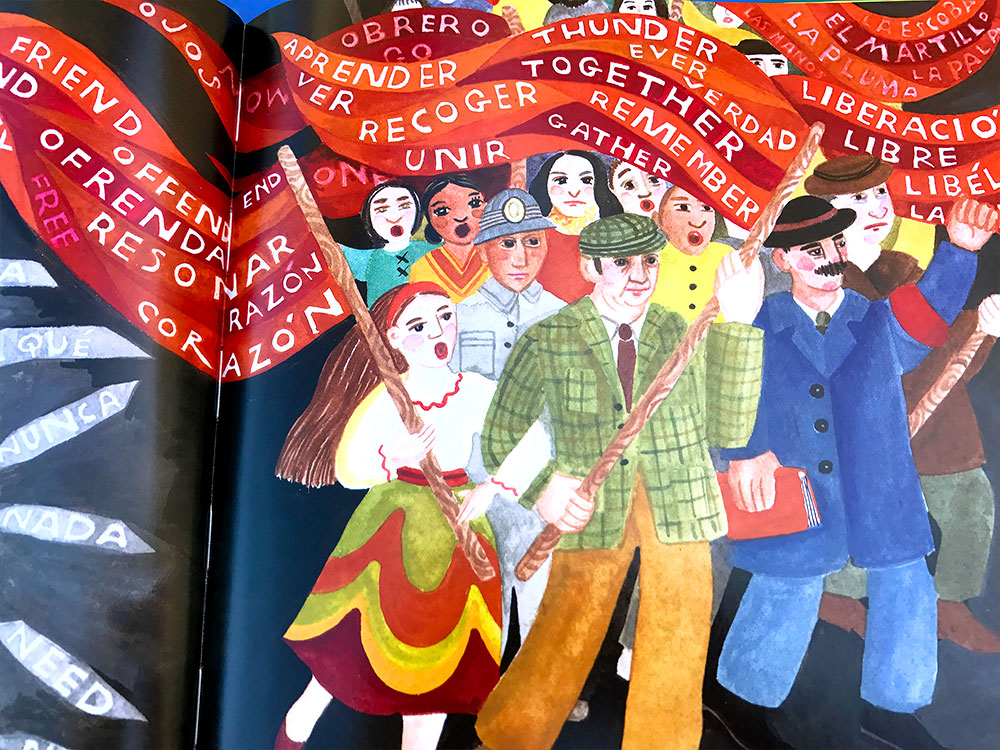

The story begins with the poet’s birth in Chile in 1904 with the given name of Ricardo Eliecer Neftalí Reyes Basoalto — to evade his father’s disapproval of his poetry, he came up with the pen name “Pablo Neruda” at the age of sixteen when he first began publishing his work — and traces his evolution as a writer, his political awakening as an activist, his deep love of people and language and the luminosity of life.

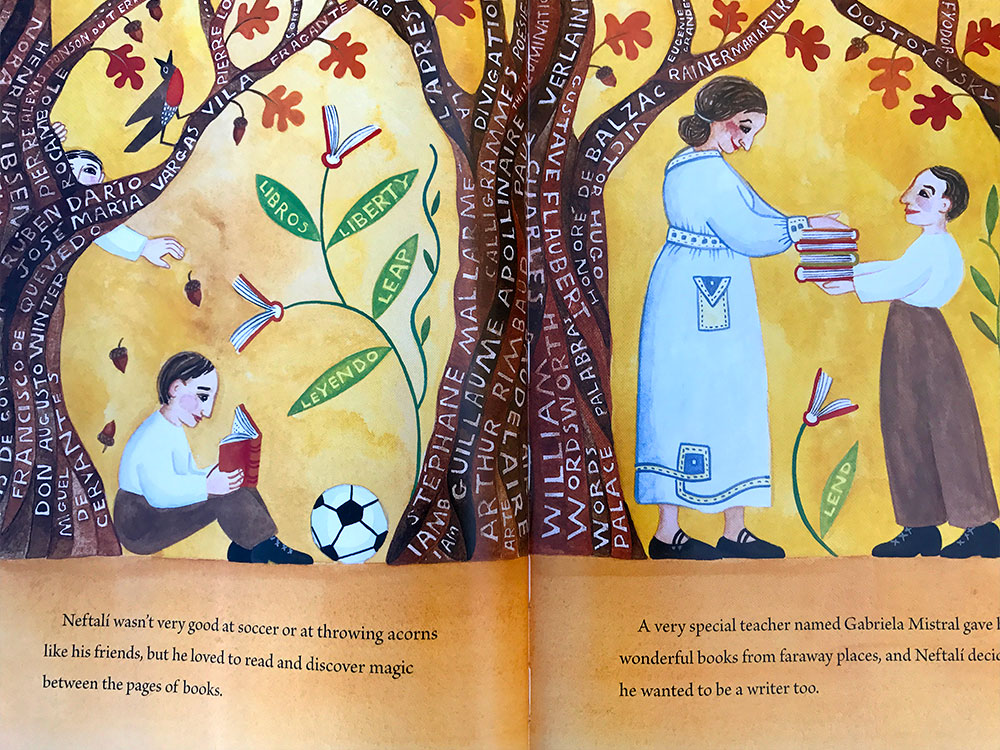

Neftalí wasn’t very good at soccer or at throwing acorns like his friends, but he loved to read and discovered magic between the pages.

Embedded in the story is a sweet reminder of what books do for the soul and a heartening assurance that creative genius isn’t the product of conforming to common standards of excellence but of finding one’s element.

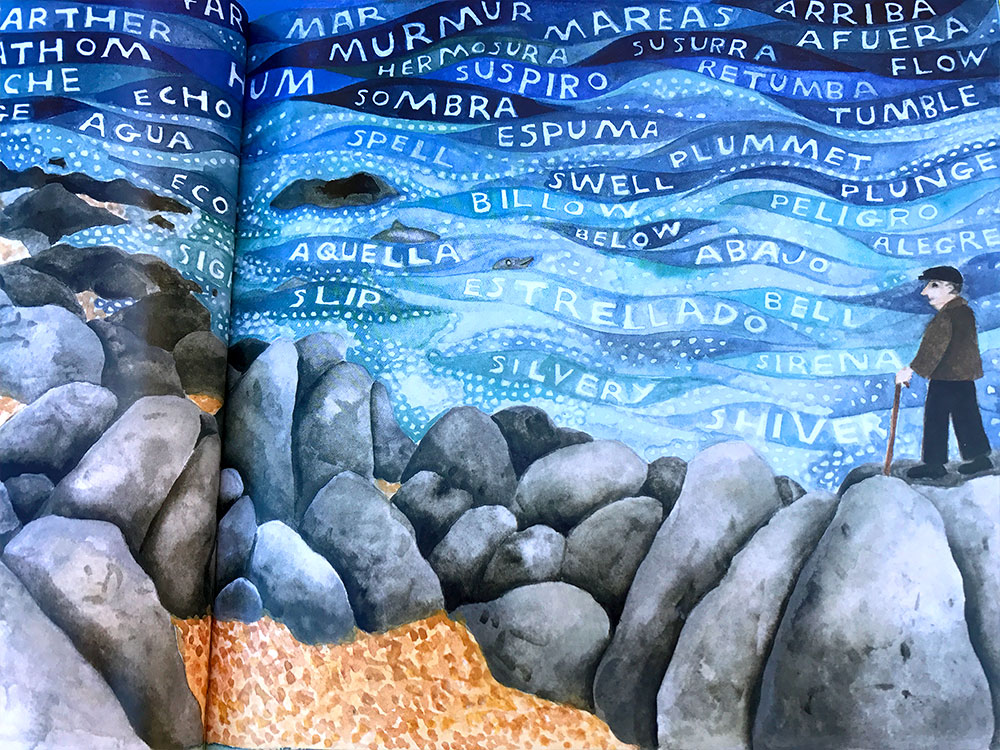

In fact, the book is as much a celebration of Neruda as it is a love letter to language itself — swirling through Paschkis’s vibrant illustrations are words both English and Spanish, beautiful words like “fathom” and “plummet” and “flicker” and “sigh” and “azul.”

Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People is exuberant and enchanting in its entirety. Complement it with Bon Appetit! The Delicious Life of Julia Child, written and illustrated by Jessie Hartland, and On a Beam of Light: A Story of Albert Einstein, written by Jennifer Berne and illustrated by Vladimir Radunsky, then treat yourself to this bewitching reading of Neruda’s “Ode to the Book.”

THE MARGINALIAN