In Conversation

JOHN ASHBERY with Jarrett Earnest

|

| John Ashbery, Late for School, c. 1948. Collage, 12 1/2 × 8 inches. Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York. |

Jarrett Earnest (Rail): Instead of asking you a lot of specific questions about poems, which is what people usually do and which I find quite tedious, I’m going to ask you more “human being” type questions, if that’s ok.

John Ashbery: Okay.

Rail: One thing that struck me in the chronology in the Library of America edition Ashbery: Collected Poems 1956 – 1987: “1936—Reads about landmark Surrealism exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in Life magazine; decides to become a surrealist painter.” You would have been about nine. It’s interesting to note that you were first introduced to Surrealism through visual art, rather than poetry.

Ashbery: Yes—actually through that article. At the time I read Life every week, like everybody else in the country. I don’t think I decided to become a Surrealist painter when I read it. I used to take art classes at the art museum in Rochester, near where I grew up. I told the teacher about this and she said, why don’t you try something Surrealist, so I did these rather crude pictures. It just seemed like a great idea. Every day, I’d do a lot of drawings, usually of women in beautiful gowns—maybe I thought I’d be a dress designer, which I would have been quite good at. The art department closed in the little school I went to so they allowed me to go to Rochester to take the art class there. That was in the late-’30s. Aside from a few childhood ventures, I didn’t start writing poetry seriously until the early 1940s. When I started writing poetry I carried it over into that.

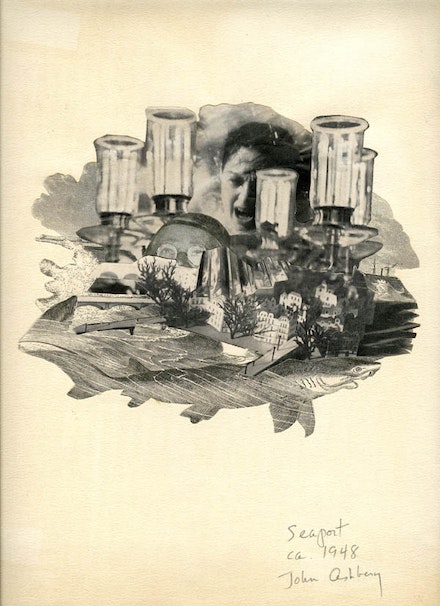

|

| John Ashbery, Seaport, c. 1948. Collage, 10 1/2 x 8 inches. Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York |

Rail: Do you have any recollection of when you first thought that you wanted to be an artist or a poet, or what that might have meant?

Ashbery: I think I always did.

Rail: In several places you’ve downplayed or disparaged your work as an art critic. I wonder why you feel the need to do that?

Ashbery: First of all, I felt that I was never really qualified to be an art critic. The only reason I did it was because I needed to earn some money, which wasn’t the best way of making rent by any means.

Rail: You started writing for ARTnews. When you first met Thomas B. Hess, the legendary editor there, to get a job writing art criticism, what did he say?

Ashbery: I was living in New York after spending two years in France as a Fulbright student and I didn’t have any job and I was taking graduate courses in French at NYU thinking I would get a Ph.D. and become a professor of French. I was sharing an apartment with James Schuyler and although it was only $58 a month it was hard coming up with half of the rent, so Jimmy, who was already writing for ARTnews, said why don’t you write criticism? I said, I don’t know how to do that. He said, sure, it’s easy, and Tom Hess prefers to have poets writing art criticism because they have a fresh approach without unnecessary knowledge about the subject. Also, I think he could pay poets slave wages. I went to see Tom and he was a little forbidding and I felt of course very unqualified to be there. He assigned me an article, which was the first thing I ever wrote about art, which was a review of a show by Bradley Walker Tomlin—did you ever hear of him?

|

| John Ashbery, Desert Flowers, 2014. Collage, 9 3/4 x 14 inches. Private Collection, Courtesy Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York. |

Rail: Yes, a terrific artist, but hidden—I’ve seen very few in person. He was gay, wasn’t he?

Ashbery: Yes! I often wonder if that wasn’t why Tom assigned it to me.

Rail: So he immediately knew you were gay?

Ashbery: Oh, probably. I don’t know, we never talked about it; not then, at least. So I did that and he liked it, and then he had me writing monthly reviews of gallery shows. They claimed to cover every show in New York. The really forgettable ones were the ones in the back of the book which were very short and paid five dollars, which was nice to have.

Rail: Well they were just a couple lines, right? Sounds like good money to me.

Ashbery: Yeah, subway fare.

|

| John Ashbery, Cushing’s Island, 1972, collage, 3 1/2 × 5 1/2 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Tibor de Nagy Gallery. |

Rail: Was there art that was easier or harder for you to write about?

Ashbery: That is an interesting question, which I don’t think I can answer. It was obviously pretty easy to write about Abstract Expressionist painting, since it was brand new and nobody knew anything about it, so what you had to say would be as valid as what anyone else might. Also, it’s not unlike the poetic process in its being a record of its own coming into being, so I guess that might have been easier. I can’t think of any that were difficult, unless they were historical and required a lot of research, but I don’t remember that I wrote very many of those.

Rail: In a conversation you did with Kenneth Koch in the mid-’60s there is a wonderful exchange: Koch says “Have you ever been physically attacked because of your art criticism?” You say, “No, because I always say I like everything.” Then he says, “Would you say that is the main function of criticism?” to which you answer, “If it isn’t it should be.”

Ashbery: Well, I suppose there is a grain of truth in that!

Rail: In the introduction to one of the volumes of your translations from French, there is an aside that says you’d keep parts of your childhood diaries in French so that no-one could to read them.

Ashbery: Yes!

Rail: What kind of feelings were you writing in French?

Ashbery: Crushes on boys.

|

| John Ashbery, Promontory, 2010 |

Rail: I also read that before you went to college your mother read your letter to a boy revealing you were gay, and I wanted to know more about that: when did you know you were gay?

Ashbery: Well, first of all the word “gay” didn’t really exist then. The concept might have been more nebulous than it is now, but I knew I was attracted to boys. I spent two years at Deerfield Academy. My senior year they decided I was too young to go to college, having skipped a year in grade school, so I ended up spending two years there. At the end of the second year I got accepted to Harvard, where I went in the summer of 1945. I graduated Deerfield in June and went to Harvard in July. I had had this good friend the first year at Deerfield who had already graduated, who was gay, and I wrote him a letter bringing him up to date on all the gossip that had happened in the last year, and not much did, and that was the letter that my mother found. I left it out without sealing it and went away for the night and of course my mother naturally read it and was very upset. She somehow forced herself to forget about it because it was never referred to after that. She said she never told my father, though I’m sure she did. In any case, he never mentioned it to me.

Rail: Did your mom commonly go through your things as a child?

Ashbery: Oh, sure; that’s why I wrote in French in my diary. I believe one of my techniques was to use the word garçon, but I figured she might very well know what that means, so I used the slang word gar instead.

|

| John Ashbery, Family, 2011 |

Rail: In an interview from the mid-‘60s you said, “My pronouns can never be trusted to refer to any one person for any length of time, I believe in a kind of polyphonic effect that I try to get” which interests me immensely.

Ashbery: I’m sort of notorious for my use of the pronoun “it” without explaining what it means, which somehow never seemed a problem to me. We all sort of feel the presence of “it” without necessarily knowing what we’re thinking about. It is an important force just for that reason, it’s there and we don’t know what it is, and that is natural. So I don’t apologize for that, though I’ve been expected to on many occasions.

Rail: How does that relate to writing criticism, where the job is to describe the “it” and define the “I”?

Ashbery: Writing criticism is a completely different procedure. Your task is pretty well defined by what you’re writing about. There are pictures or sculptures, which are concrete and present, and the presence of “it” is not a problem, I think, though I’ve never thought about that before.

Rail: You’ve made both collaged poems and collaged pictures—how does it work differently to collage words instead of images?

Ashbery: I don’t know, though undoubtedly it does. It’s much more difficult to control the meaning of language, but if you’re using an image cut from a picture, which is just there, it may reflect on the other elements of the collage, but not in the vast way that language allows or uses.

Rail: Because the abstraction of language can move further, or with more multiplicity?

Ashbery: I think so, yes.

Rail: Have you always made collages?

Ashbery: I think I started when I was in college. My roommate and I used to make them. I still have a couple from that period, one of which was in the show that I first had, at Tibor de Nagy Gallery in 2008. A bunch of others unfortunately got thrown out when our house was sold—I wasn’t around when it happened, not that they were works of great importance but it would be nice to have them. One of those I still have is really good, in fact I think it may be one of the best I’ve done.

Rail: What makes it the best?

Ashbery: It’s just complete. It was taken from a 19th-century children’s book illustration. The top half showed a little boy running off to school with his little sister waving. In the bottom half he is coming back from school. In the top one I put a large head of a bird looking through the gate that the boy is about to come through. In the bottom one, coming back, he has the bird’s head replacing his head, and the girls are looking apprehensive, as well they might. There is a black figure in a loin cloth behind the girls, approaching the scene. It’s pretty creepy.

Rail: Mysterious, suggestive of some undefined narrative. It reminds me of your translations of Giorgio de Chirico’s novel Hebdomeros.

Ashbery: I felt tremendous love for that text. It’s so precious. Especially when you consider it was written by de Chirico, who was known as a painter and not as a writer, but who invented a literary style that no one had ever used before. He was also an old grouch. I actually met him once in New York. He had a show at the museum in Columbus Circle, and I wanted to get permission to translate all of Hebdomeros—he had sent me a letter once, in response to my letter, saying I could translate a section, but I wanted to do the whole thing, even though it had already been translated by somebody else. I was passed along by these two Americans who were apparently his dealers in Rome, who I had to meet first, then his wife, then finally I got to meet the great man himself and I said how much I admired Hebdomeros and how much I’d like to translate it and he just waved his hand “eh!” and that was the extent of our conversation. So I never did the rest of it because the rights situation seemed unclear.

Rail: Dante supposedly knew all of the Aeneid by heart, which must entail a certain kind of knowing. While translation is not memorizing, it seems that the act of translation would give you a special relation to the text, some similar kind of internalization. Or is that just my fantasy as a non-translator?

Ashbery: Maybe it’s true. I certainly feel on an intimate level with Rimbaud and other things I’ve translated. I also may feel that this will add some dimension to my own writing having done this exercise but I’m not sure that I really feel that.

Rail: What did you learn about Rimbaud from translating all of Illuminations, which you published in 2011?

Ashbery: I felt more at ease in reading him having translated him. It’s something I could walk around in and observe once I had translated it. I’m always waiting for possible repercussions in my own writing from translating him, which are probably there, but I’m not sure what they are.

Rail: A lot of people resort to poetry when they are in love, or are upset. I wonder how falling in love affected your poetry, or your relationship to language?

Ashbery: Actually, my first love was the summer I was sixteen with a boy a year older from Massachusetts who was working on a farm nearby. He was the one who first told me about Rimbaud.

Rail: Really!

Ashbery: He had read him. And he showed me the short poem, Ô saisons, ô châteaux, / Quelle âme est sans défauts?—which I thought was the most beautiful thing I’d ever read. I think I had already begun to write poetry when I first met him, but that opened a more intriguing way of poetry. My early poems are really embarrassing now and he was very kind about them but obviously he didn’t think they were worth much, offering genial criticism. And he also knew the poet Robert Francis, who was like sort of like Robert Frost—younger and lesser known—who lived in Amherst, near my friend.

|

| John Ashbery, Fountain, 2010, collage, 5 3/4 x 3 1/2 inches. Courtesy the Estate of the Artist and Tibor de Nagy Gallery, New York. |

Rail: Did you have a dramatic parting?

Ashbery: He went home to Amherst and I was going to Deerfield that September for my first year, and after he left I felt very guilty about having done all this and I stopped replying to his letters. He was very upset.

Rail: That must have cemented your relationship to both French and poetry. I think about you writing your private feelings in French, and then having this intense romance featuring Rimbaud! Fabulous. When you finally ended up in France, what about it agreed with you?

Ashbery: What’s not to like, as they say. Just about everything, except the uncomfortable quarters I was obliged to live in, squalid rooms.

Rail: It’s striking you left New York for Paris when you did, especially in an art context. French art was being eclipsed by American art, at exactly the moment you found yourself in Paris.

Ashbery: I didn’t really mind about that. I wasn’t really a part of what was happening in New York—I didn’t know the artists really, not the way Frank O’Hara got to know them. They couldn’t have cared less about me; I was an unknown poet. That was the visual arts anyway, which was something I liked along with poetry, but poetry was what I was mainly interested in. For a long time, I wasn’t really able to read French well enough to tell if they were producing great poetry or not—turned out they weren’t. Just the life of the place was what attracted me. I didn’t feel deprived by not being in the hot artistic center.

Rail: Why did you decide not to finish your Ph.D. on Raymond Roussel?

Ashbery: What I really wanted to do was just go back and live in Paris. I went back and did research on Roussel and after a while realized I didn’t want to go back to New York. I was living with a French friend whom I met when I had first arrived and I just wanted to stay with him so little by little I managed to scrounge out a living while I got a job writing reviews for the Herald-Tribune (which payed miserably, $15 an article) but with that I was able to get assigned reviews at other publications. None of this enabled me to live very comfortably, but, on the brink of poverty, I was able to stay in Paris, which was what I wanted.

Rail: You have said in the past that most of your early writing, when you were an “unknown poet”, was done without the expectation of an audience or even of publication. But by the mid-’70s you became so lauded. How did that affect the way you approached writing?

Ashbery: When I first started writing poetry I thought, this is great, people will love this, I’ll become a celebrated poet, and that turned out not to be the case at all. My first book Some Trees (1956) published in an edition of 800 copies, took eight years to sell out. And the next book, The Tennis Court Oath (1962) was even less successful. So then I thought, well people aren’t going to think I’m a great poet. So what do I do? Do I go on writing because this is what I like to do, or should I give it up and take up something else?—like macramé? I decided I’m going to go on doing it—I like doing it and the hell with them. Then gradually I somehow picked up readers, and eventually, with Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror (1975) I won the three main poetry prizes and was suddenly certified as a poet after not counting as one for so long.

Rail: Several of your books, including my favorites, have the dedication for David, who I imagine is David Kermani. You two have been together a very long time and I’m interested in what you’ve learned from that long relationship. For some context of where I’m coming from, you’ve been together longer than I’ve been alive—I’m really single and really like it—so I’m curious what kind of knowledge that kind of deep partnership brings.

Ashbery: We complement each other. As you may have noticed, David is all about business and getting things done and details. I’m the other way, I’m sort of lazy and get around to doing what I’m supposed to be doing. So I need somebody to push me into shape. I think I’d known David for about three months before I noticed he’d been balancing my checkbook for me, which I never asked him to do. He just naturally gravitates to this kind of activity. He is a typical Capricorn.

Rail: And what sign are you?

Ashbery: Leo.

Rail: Me too! How did your relationship with David change your life and work?

Ashbery: I guess it changed my life by making me try to be less distracted and lazy and helping me to do the work that I wanted to do. And also making it easier for me to do it, because he’s handled so many practical aspects of my life. We’re sort of complete opposites, and are attracted by the oppositeness of the other.

Rail: I really love the Charles Eliot Norton lectures you gave at Harvard, called Other Traditions. In the one on Laura Riding you talk about the necessity of misreading her poems, or at least reading them against how she might tell you to read them, “This is what happens to poetry: no poem can ever hope to produce the exact sensation in even one reader that the poet intended; all poetry is written with this understanding on the part of the poet and the reader.” What kinds of understandings are possible through miscommunication?

Ashbery: That’s a pretty big question. Certainly the possibility of miscommunication has to be taken into account, both in writing and in communicating verbally. One has to admit that it is there while trying to get beyond it.

Rail: It seems the ways your poetry opens onto ambiguity is a means of accommodating that potential for misunderstanding but incorporating it, or orchestrating it, as a positive element.

Ashbery: That is possible, though I’ve never set out to write a poem thinking, I’m going to write this so it can accommodate being misunderstood—that doesn’t somehow come up when I’m writing.

Rail: The poets in Other Traditions, like Clare, Beddoes, Riding, are all classed as “minor poets” in that they all require a special handling to appreciate. They also all had rather dramatic, tormented lives.That kind of careful attentiveness, or special handling, seems like part of all you do.

Ashbery: I suppose in those essays I wanted to try and make amends for the misunderstandings they endured, having experienced some of it myself. Also it makes a good story.

Contributor

Jarrett Earnest

JARRETT EARNEST is a writer who lives in New York.

THE BROOKLYN RAIL

No comments:

Post a Comment