BOOKS OF THE TIMES

Sexton's Poetry: Better as Poetry Than Therapy

By MICHIKO KAKUTANI

Published: May 18, 1988

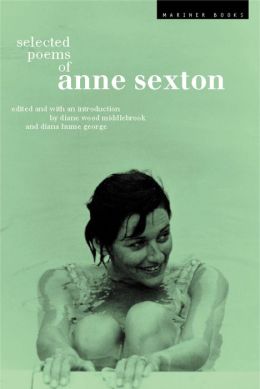

Selected Poems of Anne Sexton Edited by Diane Wood Middlebrook and Diana Hume George 266 pages. Houghton Mifflin Company. $21.95. I am filling the room with the words from my pen. Words leak out of it like a miscarriage. I am zinging words out into the air and they come back like squash balls. Yet there is silence. Always silence.

For Anne Sexton, the writing of poetry was not merely a literary exercise, a muscle-flexing routine of artistic expression. It was a kind of essential, life-giving stay against confusion - and the silence that ''is death.'' Having been hospitalized in the mid-1950's after a suicide attempt, she began writing verse at the suggestion of her psychiatrist, and though she quickly went on to earn both critical respect and wide popularity, she would continue to regard writing primarily as a means of understanding herself and her private nightmares. In the end, however, silence triumphed: in 1974, a month before her 46th birthday, Sexton committed suicide by carbon monoxide poisoning. She had been worried, say the editors of this volume, that ''she was losing her creativity.''

Sexton's great subject, of course, was herself, and her poems provide us with a continuing autobiography, chronicling everything from her breakdowns to her operations, her marriage, infidelities and divorce. At the same time, they leave behind a succession of portraits of the author - as daughter, mother, wife, mental patient and poet. Sexton as ''a possessed witch,/haunting the black air.'' Sexton as ''an angry guest,'' ''a partly mended thing, an outgrown child.'' Sexton as a rebellious teen-ager, wasting herself on boys ''and cigarettes and cars.'' Sexton as a middle-aged housewife, who ''wore rubies and bought tomatoes.'' And Sexton as an emotional invalid, ''queen of this summer hotel'' called Bedlam.

In many respects, the epigraph from Kafka that Sexton chose for her second volume of verse serves as a succinct summary of her own impulses as a poet - ''a book should serve as the ax for the frozen sea within us''; and in retrospect, her tendency to treat poetry as a form of therapy accounts for both the best and the worst in her work. Her finest poems, in which form and idiosyncratic rhyme schemes are used to contain the roiling emotions, possess a personal immediacy that grabs us and forces us into an intimate relationship with her own experiences: her repeated visits to ''Bedlam,'' where the inmates ''mind by instinct/ like bees caught in the wrong hive''; her tortured attempts to come to terms with her mother's death from cancer; her fierce and ambivalent love for her daughters; her ongoing love affair with death. The poems in ''To Bedlam and Part Way Back'' (1960) and ''All My Pretty Ones'' (1962) present a savage, almost clinical documentation of madness, illness and pain, and they do so with the authority of a witness blessed with a strong and passionate voice.

In her weaker poems, however, Sexton frequently yielded to the most self-pitying extravagances of the confessional school. Unable ever to climb out of the prison of selfhood, she could sound like a spoiled child, whiny and repetitive, self-consciously maudlin and melodramatic - a bad, greeting-card version of Sylvia Plath or Robert Lowell. Compared with Lowell or John Berryman (whose life, ending in suicide, in many ways paralleled her own), Sexton had great difficulties creating a poetic persona with any measure of imaginative detachment, an inability to find a perspective on her own problems that might have situated them within a larger social or emotional context.

With the exception of ''Transformations'' (1971), a series of verses based on folk tales, and the occasional poem in ''The Book of Folly'' (1972), her later poems grow increasingly sentimental and narcissistic. As her friend the poet Maxine Kumin once observed, many of the verses in ''The Awful Rowing Toward God'' (1975) were written in a ''white heat'' - ''at the rate of two, three, even four a day''; and the hasty, even manic composition shows. The verses here and in the even weaker subsequent volumes (''45 Mercy Street'' and ''Words for Dr. Y.'') often feel like unedited journal entries - embarrassing eruptions of pain, self-loathing and fear, unmediated by sufficient artistic discipline or control. The poems about God tend to combine discount-house blasphemy with recyclings of Sunday school pieties (''God dressed up like a whore/in a slime of green algae./God dressed up like an old man/ staggering out of His shoes./God dressed up like a child, all naked.''), while the ones about women come across as sappy compilations of romantic cliches (''and the man/inside of woman/ties a knot/so that they will/never again be separate'') or dated litanies of Stepford-wives complaints (''Suppertime I float toward you/from the stewpot/ holding poems you shrug off/and you kiss me like a mosquito'').

Because of this unevenness in Sexton's work, because ''The Complete Poems,'' published in 1981, was filled with so much dross, Diane Wood Middlebrook and Diana Hume George, the editors of this new volume of selected poems, have done the reader an enormous service in pulling together poems that, in their words, ''represent Sexton at the height of her powers.'' The reader may quibble with some of their choices: one wonders, for instance, why more samples from ''Transformations'' were not included, why so much space was alotted to Sexton's less than successful attempts at religious verse. Yet all in all, the poet is well served. For the new reader, this volume provides a solid introduction to Sexton's work; and for others, it should restore and burnish her reputation as a gifted, if limited, American poet.

+(1).jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment