|

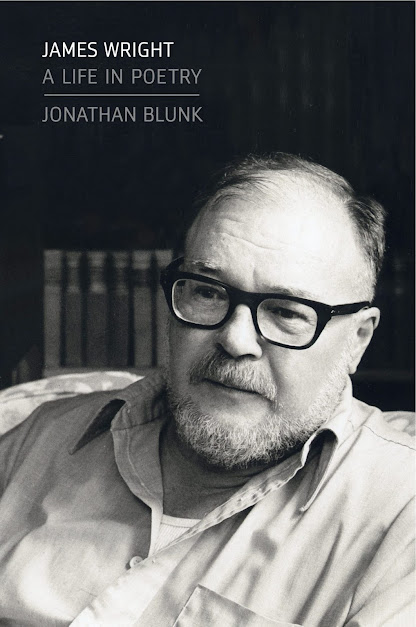

| James Wright |

James Wright

Jonathan Blunk

His First and Last Readings

Primal Ear / Theodore Roethke, James Wright, and the cult of authenticity

James Wright / Lazy on a Saturday Morning

Of the many resources I’ve mined in researching James Wright: A Life in Poetry, the most vivid have been recordings of Wright’s readings over the course of two decades, when he was a vital public figure in the world of American poetry. A strong impression of his physical presence survives in his voice, in the stories he tells, and in the poems he says—many of them written by others. Wright did not recite poems, and rarely needed a printed text. The word he used was saying poems; they were part of how he spoke, even how he thought. Wright had an astounding memory, so alert to the patterns of sound and language that some I interviewed described it as a “phonographic” memory. After saying poems in Latin, German, or Spanish, Wright would improvise his own translations. He knew countless poems by heart, as well as entire Shakespeare plays, novels by Dickens, and essays by H. L. Mencken and George Orwell—a seemingly infinite store.

For Wright’s authorized biography, I gathered and transcribed four dozen of his readings, public talks, and interviews. Included here are two poems, from readings twenty-one years apart. “A Note Left in Jimmy Leonard’s Shack” comes from the first of Wright’s readings that I’ve found, recorded in Minneapolis, Minnesota, on May 25, 1958. Wright gave his final reading on October 11, 1979, in the Harvard College Library, Cambridge, Massachusetts, saying poems from throughout his career, including “A Blessing.”

One of the finest readers of his generation, Wright joined the many itinerant poets who took to the road in the 1960s and ’70s to appear in cities and on college campuses around the country. Along with his wide knowledge of poetry and singular memory, Wright had a richly timbral voice that never lost a touch of Southern Ohioan, a slight Appalachian lilt he carried from his birthplace in Martins Ferry on the Ohio River. He modeled his expressive reading style on his great mentor, Theodore Roethke, with some of the fire and melancholy of Roethke’s friend Dylan Thomas. Thomas created a kind of template for the cross-country reading tour in the late 1940s and early ’50s, and Elizabeth Kray soon began organizing reading circuits of college campuses grouped in close proximity that could then share the cost of hosting poets. When Wright recorded fifteen of his own poems at the request of Randall Jarrell for the Library of Congress in May 1958, he had just arranged, with Kray’s help, his first extensive reading tour across New England for the coming December.

Wright had already won acclaim for his rhymed and metered verse and was publishing widely in journals and magazines when he arrived at the University of Minnesota in September 1957 to take up his first teaching appointment. The Green Wall, his debut collection, had been published in the Yale Series of Younger Poets, chosen by W. H. Auden. Saint Judas, Wright’s second book, would be of the same traditional cast. “A Note Left in Jimmy Leonard’s Shack” is a prime example of the influence of Edwin Arlington Robinson on Wright’s work: a dramatic monologue, spoken by a twelve-year-old boy to the brother of the town drunk, in five stanzas of interlocking rhyme. But something from the streets of Martins Ferry insinuates itself into Wright’s voice, as it does throughout his poetry; the material he is drawn to here creates a tension with the formal craft of the poem. When the boy utters a brief, sharp curse near the poem’s conclusion, Wright’s voice sparks to life, brushing aside decorum and convention. One realizes how much the boy cares for the poor old drunk—that is, how much the poet cares.

Wright dedicated what would be his final reading in October 1979 at Harvard College to the memory of Elizabeth Bishop, who had died a week before in Boston at the age of sixty-eight. In her honor, Wright began by saying from memory Yeats’s ars poetica “Adam’s Curse.” “Everybody knows it,” he allows, “but it doesn’t hurt to sing it again.” Of his own work, Wright chose poems from throughout his career, though he worried in his journal the night before, “I wonder what, if anything, the Harvards will make of Ohio, my Ohio.”

Wright had just returned from nine months of travel in Europe, enjoying a remarkable period of sustained writing that would appear in his posthumous volume, This Journey. He did not know at the time of his reading that the sore throat he just couldn’t shake was in fact a cancerous tumor that would take his life five months later. On the recording, Wright seems as if he were troubled by a cold. But the reading is generous and self-assured, with a storyteller’s pacing and sensitivity. Following a bravura recitation of the bitter, scalding work “The Minneapolis Poem,” Wright turned to a poem from his 1963 book The Branch Will Not Break: “A Blessing.” He often insisted that many poems in that collection, including “A Blessing,” were “just descriptions”—clearly observed moments of perception and feeling. At the time he wrote The Branch, the possibility of happiness seemed always a surprise to him. “A Blessing” owes its inspiration, in part, to translations of classical Chinese poetry, a source Wright turned to often. In this final reading of the poem, Wright throws a slight accent on the word “my” in the penultimate line, heightening an awareness of how closely he has been observing the bodies of those horses that “can hardly contain their happiness.”

Wright’s command of free verse is nowhere more evident than in the skillful enjambment of the last two lines of “A Blessing.” Expanding upon this fluency with image-based strategies he found by translating German, Spanish, and Latin American modernists, Wright had a profound influence on his peers and on succeeding generations of American poets. The Branch Will Not Break remains his most celebrated book; together with his 1968 masterwork Shall We Gather at the River, the poems Wright published in the 1960s helped assure that his Collected Poems of 1971 would be awarded a Pulitzer Prize.

But Wright never turned his back on rhymed and metered poetry. In his Harvard reading he included “A Note Left in Jimmy Leonard’s Shack,” “An Offering for Mr. Bluehart,” and an early sonnet, “My Grandmother’s Ghost”—the poem Wright said most often throughout his career. The concluding poem of his final reading is another formal tour de force, what he called “a cracked ballade” in the manner of François Villon: “A Farewell to the Mayor of Toulouse.” It was one of dozens of new poems Wright had brought back from his last journey in Europe.

Jonathan Blunk is a poet, critic, essayist, and radio producer. His work has appeared in The Nation, Poets & Writers, The Georgia Review, and elsewhere. He was a coeditor of A Wild Perfection: The Selected Letters of James Wright.

The Library of Congress is the source for Wright’s reading of “A Note Left in Jimmy Leonard’s Shack” on May 25, 1958, in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Wright’s final reading at the Harvard College Library in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on October 11, 1979, which includes “A Blessing,” is now part of the Woodberry Poetry Room’s audio archive.

No comments:

Post a Comment