An Afrikaans Poet in Amsterdam: Translating Elisabeth Eybers

February 27, 2017by Jacquelyn Pope

W

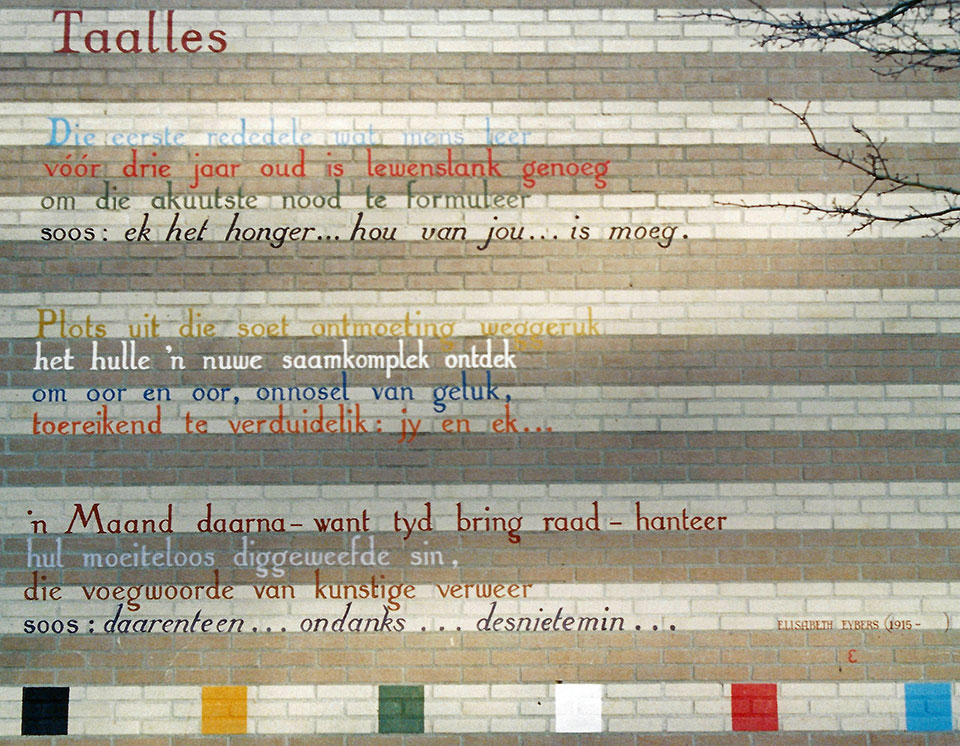

Born in 1915 in Klerksdorp, South Africa, in the former province of Transvaal, Elisabeth Eybers was the first woman to publish a volume of poetry in Afrikaans (1936). She married in 1937 and later had three daughters and a son. In 1961 Eybers left her marriage and moved to Amsterdam, bringing her youngest child with her. She arrived on the same day South Africa became a republic. It was not long after the police massacre of scores of civilians at Sharpeville and several other places, and South Africa was entering a period of isolation, world condemnation, and armed struggle that would not end until Nelson Mandela’s release from prison in 1990. Eybers left South Africa for private rather than political reasons, but she was very much against apartheid and openly condemned it, even as she resisted suggestions that she should recast her reasons for leaving or act as a spokeswoman against the regime. She also refused to abandon Afrikaans as the primary language for her poetry, once describing it as “a language created for poetry,” one that was “bare yet supple, a mixture of angst and sarcasm.” Although Afrikaans is derived from Dutch, by the 1960s it was regarded as a foreign language in the Netherlands, and South African literature in Afrikaans was basically unknown there. Eybers was able to create a readership for her work in the Netherlands and came to be held in great esteem, eventually receiving numerous literary prizes. She died in Amsterdam in 2007.

I came across her books when I was living in Amsterdam, working as a bookseller and combing the shelves for work I could read. I was wrestling with the process of learning Dutch, trying to be reconciled to being a stranger in an adopted country, and feeling an acute absence of poetry. Her work stood out to me immediately, because of its spareness and evident craft, but also because of the “slight strangeness” (her own phrase, used to describe herself in a poem) of the way the Afrikaans looked on the page. Eybers, I read, was an established poet who’d lived in Amsterdam for decades, a woman who lived her day-to-day life in Dutch but basically refused to write poems in it. That stubbornness was enormously appealing to me: it was a good reminder of the necessity of independence to poets.

The music underlying her poems was readily apparent, even before I could really read them. As I became more familiar with her work, I also felt a kind of kinship with the voice of the poems, her descriptions of negotiating the habits, weather, and histories of two vastly different places on a daily basis. There was something else, too—harder to put into words—the business about being from a rougher place, a nation where violence was inexcusably common, an “uncivilized” place, as Europeans would often characterize it. There was also a felt shame about national history and government actions, along with the knowledge that there are many varieties of resistance to dominant culture, and that these don’t necessarily register across cultures. Most of all, what I found in her work was a vivid rendering of the experience of passing for someone who belonged, until the act of speaking betrayed otherness. At the same time, the poems depicted access to another language as a kind of interior refuge. Words represent another life. This was in no way sentimental, instead it pointed to the polarities of human experience: of life and love but also doubt and fear, connection and alienation. The world of her poems is quotidian, domestic, yet the struggles in them are huge, and human: for intimacy, for honesty, for the chance to be really seen by another, the struggle to be honest with the self. And, also, reckoning with death.

The first poem I tried translating begins with a question, “that same strange question” she calls it: “Have you come to feel at home in this country?” She calls the question strange, not least I think because it admits only one response, really, and one that isn’t hers. She goes on to write:

That simple things, things you formerly took for granted, perhaps never noticed at all, can be some of the strangest things, can become impediments—this is a recurring motif in her work, and it sometimes lends an unsettled, even menacing quality to streetscapes, landscapes, nightscapes, and echoes the immigrant’s off-kilter experience. Things have their opposites across the world, or in the poet’s memory. But what is a rightful place, and who can claim such a thing?

The layered nature of the transactions in Eybers’s poems also involves movement between time present and past, and the work of rendering new terrain in language forged in an altogether different place. Her poems contain humor and surprises, all with great subtlety: wonderful to read and demanding to translate. In later life she wrote many poems about aging, involving a leave-taking of the known, a frustration with the physical self, a blending of the past and the future, and a kind of waiting and watching between them.

Translating poetry almost inevitably involves the translation of a private language and familiarity with its symbols, in addition to the cultural load carried by the source language itself—with Eybers this is especially the case. Her Afrikaans remained very pure, according to critics; at the same time her poems contain some Dutch words and references to the climate and landscape of the Netherlands that were probably exotic to her South African readers. The world in her poems contains very different natural and built environments. The sense of interiority in her work, and the precision of tone that carries meaning, are exactly what makes her poems bear such convincing, truthful witness to the world.

Oak Park, Illinois

Jacquelyn Pope’s first collection of poems, Watermark, was published by Marsh Hawk Press; Hungerpots, her translation of the Dutch poet Hester Knibbe, was published by Eyewear. She is the recipient of a 2015 NEA Translation Fellowship and a 2012 PEN/Heim Translation Fund grant. She recently translated four poems by Elisabeth Eybers and three by Hendrik Marsman for WLT.

No comments:

Post a Comment