|

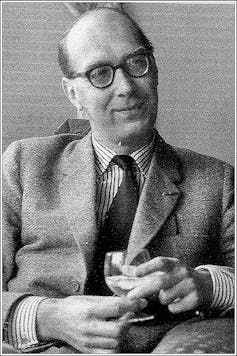

| Philip Larkin |

Was Philip Larkin stifled by his job as a librarian? New research suggests he was rather dedicated

Named Britain’s greatest postwar writer by the Times in 2008, Philip Larkin remains justly celebrated as a wry observer of life’s routines, banalities and quiet poignancies. He was a writer who once spoke of poetry as “enhancing the everyday”.

Yet much of Larkin’s reputation as a great British poet rests on the widely-held assumption that Larkin would have been greater still were it not for the demands of his day job as a librarian at the University of Hull between 1955 and 1985. In truth, there is much in Larkin’s poems and letters to support the view that Larkin was a reluctant librarian.

Now, as we celebrate the centenary of Philip Larkin’s birth in 1922, new research at the University of Hull’s Larkin Centre for Poetry and Creative Writing reveals Larkin’s dedication for his day job as a librarian at the University of Hull.

The reluctant librarian?

“Work is a kind of vacuum, an emptiness,” Larkin writes in a published letter to his long-term companion, Monica Jones, soon after he arrives in Hull. “God, the people are awful,” (May 9 1955). Nine years later, in the poem Toads Revisited, Larkin finds solace in the soothing routines of his day job. However, he continues to moan to Monica in the early 60s about the “woundy dull” work dinners he is forced to attend (28 November 1963).

Larkin’s reputation as a reluctant librarian is today cast in bronze, by Martin Jennings’ in his statue of Larkin at Hull Paragon Railway Station. In it, the poet is seen dashing for a train to London and fretting, in lines from the The Whitsun Weddings, about being “late getting away” from work.

Yet, while there is evidence to suggest Larkin found his work as a librarian distracting and dull, we must guard against taking what he says in his poems and published letters at face value.

Larkin confesses, in an unpublished letter to Monica Jones, which now resides in Hull’s university archives, that “my remarks about myself are not very trustworthy”, and “are invariably designed to conceal rather than reveal” (June 1 1951).

This suggestion that Larkin’s private letters are not always reliable finds echoes in the words of Larkin’s contemporary, the Hull academic John Saville, whose correspondence with and about Larkin survives in the university archives. Writing to the Guardian in a letter published on October 20 1999, Saville notes the disjunction between the views Larkin expresses in “private letters” and his “courteous and helpful” demeanour as a librarian.

Saville draws on his working relationship with Larkin for three decades to argue that Andrew Motion, in his 1993 biography Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life, “pays too little attention to Philip’s working life as a serious and conscientious librarian”.

New light on Larkin’s ‘day job’

New research at Hull’s Larkin Centre is beginning to corroborate this picture of Larkin as a dedicated librarian, drawing on little-known records in Hull’s university archives of Larkin at work. These include minutes of library committees, records of Larkin’s correspondence as a librarian, and interviews with Larkin for the University of Hull student newspaper, The Torchlight.

The Larkin we encounter in these archives is instead an energetic figure, posing for staff photos and even contributing a self-portrait for a library staff Christmas party in 1963. He was so proud of the library and its collections that he expresses genuine surprise at student criticism of the library in a November 1969 issue of The Torchlight.

“I was under the impression,” Larkin writes to the editor of Torchlight, “that the Library is the one thing in the University of Hull which its students can claim is better than in any other university of our age and size.”

It would seem Larkin was quite proud of the library at Hull and in his poetry, he expressed the importance and value of such institutions for everyone, particularly in the poem Library Ode:

New eyes each year

Find old books here,

And new books, too,

Old eyes renew;

So youth and age

Like ink and page

In this house join,

Minting new coin.

The views Larkin expresses in one poem or collection of letters, therefore, are not always consistent with the views he expresses in other contexts. No one poem, archive or collection of letters can give us direct access to Larkin “the man”.

In an interview for Torchlight in February 1961, Larkin was asked directly, “Do you feel you are two people?” “Reading your poetry,” the interviewer continues, “I get the impression that the poet thinks the librarian is in a rut: does the librarian want to get out of the rut?”

Larkin had written to Monica Jones just four years beforehand, on January 29 1957, to confess he was “playing the fool” as a librarian with “nothing to show for it” as a poet. But to the student reporter, Larkin’s reply was far more positive about his dual role as poet and librarian: “I’m not two people for tax purposes. And in fact the poet feels very grateful to the librarian. He keeps them both.”

THE CONVERSATION