Neither Roethke, the son of a greenhouse owner from Saginaw, Michigan, nor Wright, the son of a factory worker from Martins Ferry, Ohio, regarded a prizefight as an incongruous setting for poets. On the contrary, they imported the vocabulary of boxing—its swagger and its feuds—into their discussions of the poetry world. “Allen Tate,” Wright assured Roethke, “certainly seems to think you’re the Heavyweight Champion of contemporary American poetry.” This must have delighted the older poet, who approached his rivals in a fighting crouch: “Those limp-pricks,” he bragged, “I can write rings around any of them.” And, in a letter to James Dickey, Wright insisted that without “the high joy which is all that matters . . . poetry is considerably less interesting than boxing.”

For all these masculine growls, though, there have been few American poets more acutely tenderhearted, more genuinely and at times dismayingly sensitive, than Roethke and Wright. Roethke’s great subject was the secret life of flowers, plants, and children, while Wright allied himself in his poetry with the dispossessed and the outcast. Both poets were deeply sentimental about women, especially after each found happiness in a late marriage. And they were still more vulnerable on the subject of fathers—the taciturn, unemotional men about whom Roethke and Wright wrote some of their best poems.

No wonder that, in their letters, they stepped so gingerly around the paternal element in their relationship. “I’ve spent nearly the whole of three sessions with my doctor yacking about you,” Roethke wrote Wright in 1958. “Apparently you’re more of an emotional symbol to me than I realized: a combination of student-younger brother—something like that. (I even shed a tear or two.)” Wright was equally careful to avoid the language of fathers and sons: “I’ve never directly told you what I think of you, because I’m afraid you would think I am turning you into a father. I swear I never have thought of you as a father.” Instead, Wright relaxed into a more comfortable metaphor: “I myself feel funny about writing it down on paper. It’s as though I were reminding myself that I am breathing, or that I am happy, or that I just won a fist-fight.”

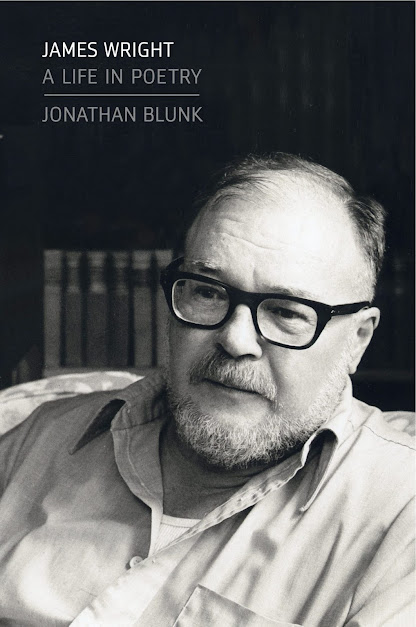

Decades have now passed since their sadly premature deaths—Roethke’s in 1963, Wright’s in 1980—and today they need to be reintroduced to a generation of readers who are likely to know them only from a few anthology pieces. It is a nice coincidence, then, that new editions of both poets’ work have recently appeared: “Theodore Roethke: Selected Poems” (Library of America; $20), edited by Edward Hirsch, and “James Wright: Selected Poems” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux; $13), edited by Robert Bly and Anne Wright. A large volume of Wright’s selected letters, “A Wild Perfection” (Farrar, Straus & Giroux; $40), has also just been published. Reading the two poets side by side helps their distinctive gifts to stand out sharply—along with their equally suggestive limitations. For Roethke and Wright both hoped that poetry could be a communion of souls, beyond or below the level of literature. But over the course of their careers they paid a high aesthetic price for their belief that earnestness could make a poem live.

The sense that, by the nineteen-forties, modern poetry had become too difficult—too remote from ordinary language and subjects, too hard to understand—was practically the only thing that united American poets of the mid-twentieth century: academic and populist, the students of John Crowe Ransom and the companions of Allen Ginsberg. The thirst of these poets—those born, roughly, between 1905 and 1930—for an alternative to the strenuous complexities of high modernism, as defined by the example and precept of Eliot and Pound, led to an explosion of new styles in mid-century American poetry: the Beats, the confessionalism of Robert Lowell and John Berryman, the projective verse of Charles Olson, and the “deep image” poetry with which Wright would be associated.

Yet Roethke and Wright were unusual in their early and intense mistrust not just of modernism but of the whole idea of poetic sophistication. Each was the product of a decidedly unliterary Midwestern setting—before Wright, the last writer to emerge from Martins Ferry, Ohio, had been William Dean Howells—and retained a lifelong suspicion of cleverness. To justify their calling, they had to insist that poetry had more to do with authenticity than with artistry.

As early as 1926, when Roethke was a sophomore at the University of Michigan, he was already laying special claim to “sincerity,—that prime virtue of any creative worker.” “I write only what I believe to be the absolute truth,” he maintained in an essay for a writing class, “even if I must ruin the theme in so doing. In this respect I feel far superior to those glib people in my classes who often garner better grades than I do. They are so often pitiful frauds,—artificial—insincere. . . . Many an incoherent yet sincere piece of writing has outlived the polished product.”

For a few fortunate years, in the second half of the forties, Roethke did succeed in making magic out of inarticulateness. His best and most characteristic poems concoct a new language for the shapeless urges of the unconscious. “One belief: ‘One must go back to go forward,’ ” he wrote to the critic Kenneth Burke in 1946. “And by back I mean down into the consciousness of the race itself not just the quandaries of adolescence, damn it.” In “Open House,” his 1941 début volume, Roethke’s verse was still constrained by the formal neatness of his youthful influences—especially Louise Bogan, the poet and longtime poetry critic for The New Yorker, who was briefly Roethke’s lover. Even in his early poems, however, he was drawn to images that could not help seeming Freudian and Jungian: massive subterranean forces, painful hidden blockages. “The teeth of knitted gears / Turn slowly through the night, / But the true substance bears / The hammer’s weight,” he wrote in “The Adamant.”

Roethke had wandered into his true subject before he discovered a style that could accommodate it. The creation of that style was an arduous triumph, requiring him to return to the primal scenes of his own childhood. His biographer, Allan Seager, records that Roethke, while working on the poems of his best book—“The Lost Son and Other Poems,” published in 1948—sometimes went around the house naked, a token of a larger stripping down.

The first fruit of this effort was the famous “greenhouse poems,” in which Roethke re-creates the vegetable world of his earliest years. Roethke’s family operated one of the largest nurseries in Michigan, thus allowing him to fill his poems with immediately legible symbols of psychic growth—roots, stems, and blossoms. But it took Roethke’s talent for powerfully indirect evocation to make the greenhouse not just a metaphor but an eerily living presence, as in “Root Cellar”:

And what a congress of stinks!— Roots ripe as old bait, Pulpy stems, rank, silo-rich, Leaf-mold, manure, lime, piled against slippery planks. Nothing would give up life: Even the dirt kept breathing a small breath.

Nearly a century and a half after Wordsworth, Roethke manages to invent an entirely new kind of nature poetry, in which the earth is not reassuringly earthy but teeming and alien. At times, Roethke’s greenhouse even becomes surreally menacing: “So many devouring infants! / Soft luminescent fingers, / Lips neither dead nor alive, / Loose ghostly mouths / Breathing.” Lines like these, from “Orchids,” show just how much Sylvia Plath learned from Roethke about making the reader shiver.

In “The Lost Son and Other Poems,” Roethke also began another major sequence that he would wrestle with for the next several years—what he described as “a series of longer pieces which try, in their rhythms, to catch the movement of the mind itself, to trace the spiritual history of a protagonist (not ‘I’ personally but of all haunted and harried men).” If poems like “Weed Puller” had shown the poet pressing himself as close to nature as he could get—“Me down in that fetor of weeds, / Crawling on all fours”—Roethke’s new style attempted to vault the barrier of sentience, to speak with nature’s own voice.

From “The Lost Son and Other Poems” through his next book, “Praise to the End!” (1951), to “The Waking” (1953), Roethke experimented with this new style. But he never accomplished more with it than he did in “The Lost Son,” the first poem in the sequence. Like “The Waste Land,” whose influence is profound but seldom obvious, “The Lost Son” dispenses with plot and argument for the sake of a hypnotically effective voice. The poem charts the emotions of a man mourning the death of his father, and it progresses through a chain of moods: grief, nostalgia, regression to childhood terrors, and, finally, a tentative reawakening to adulthood. Appropriately, Roethke draws from the deepest wells of the English language—Mother Goose, Shakespeare, the Bible—in order to create a new idiom for primal experience:

All the leaves stuck out their tongues; I shook the softening chalk of my bones, Saying, Snail, snail, glister me forward, Bird, soft-sigh me home, Worm, be with me. This is my hard time.

“The Lost Son” is the peak of Roethke’s inventiveness as a poet. But his attempt to extend its discoveries into a whole sequence revealed the fragility of this technique: without the momentum of narrative, it quickly grows static and repetitive. There are wonderful passages in “Praise to the End!” that manage to capture childish orality and sexuality with a disturbing vividness. Yet by the time he wrote “O, Thou Opening, O,” from “The Waking,” even Roethke seems to have grown impatient with his style: “And now are we to have that pelludious Jesus-shimmer over all things, the animal’s candid gaze, a shade less than feathers . . . I’m tired of all that, Bag-Foot.”

When Roethke tried to return to a more explicit and formal kind of poetry, the limits of his sensibility were harshly exposed. (“Ted had hardly any general ideas at all,” Auden reportedly said.) And his late poems, from “The Waking” through the posthumous “The Far Field” (1964), are crowded with limp, quasi-mystical abstractions: “I learned not to fear infinity, / The far field, the windy cliffs of forever, / The dying of time in the white light of tomorrow.” What is most disappointing in Roethke’s late work is the way he fell back into emulation of the established modernist idols, especially Yeats and the Eliot of “Four Quartets.” Imitation as direct as Roethke’s of Yeats, in “The Dance,” is usually found only in very young poets, not in accomplished masters. It was as though, having used up his poetic capital—his childhood—Roethke looked to those authoritative voices for reassurance.

The failures of his late work confirm that Roethke’s real subject was his own inwardness; he wrote best when he avoided direct statement in favor of tremulous connotation. That is why Roethke was always at a loss when asked what his poems meant. They could not be elucidated, he knew, only intuited. “Believe me,” he adjured the reader in a 1950 “Open Letter,” “you will have no trouble if you approach these poems as a child would, naïvely, with your whole being awake, your faculties loose and alert.”

Long before he met Roethke, James Wright shared his view of sincerity as the central literary value. In 1946, the eighteen-year-old Wright sent some of his poems to a professor who had offered encouragement. “As you read them,” Wright warned, “you will be conscious of the absence of a syllable here and there, and even of the discarding of iambics altogether. I would rather sacrifice technical skill than sincerity.” Throughout his career, Wright, still more than Roethke, would gamble on the obvious intensity of his emotions—his loneliness, compassion, wonder—to accomplish more than mere “technical skill” ever could.

Wright’s revulsion against the sterility of technique was all the more extreme because of his early proficiency as a writer of traditional verse. His first book was characterized not by audacity but by a highly polished literary language: “For who could bear such beauty under the sky? / I would have held her loveliness in air.” Yet Wright had emerged from a still less literary milieu than Roethke. “My mother had to leave school when she was in the sixth grade, my father had to leave when he was in the eighth grade,” Wright recalled near the end of his life. “He went into the factory when he was fourteen and my mother went to work in a laundry.”

Wright would often honor his father’s lifetime of manual labor in his verse: “one slave / To Hazel-Atlas Glass became my father,” he wrote in “At the Executed Murderer’s Grave,” one of his best early poems. But already in that poem, from his second collection, “Saint Judas” (1959), Wright was moving away from pastoral elegance, straining to incorporate the brutal realities of working-class Ohio:

I waste no pity on the dead that stink, And no love’s lost between me and the crying Drunks of Belaire, Ohio, where police Kick at their kidneys till they die of drink.

The stylistic revolution that was to produce Wright’s best poetry was touched off by a passing insult in a 1958 review, by James Dickey, of the anthology “New Poets of England and America,” where Wright took his place alongside many of the young writers who were to dominate American poetry for the next several decades—including Richard Wilbur, Adrienne Rich, and Anthony Hecht. But Dickey found the anthology “representative of a generation that has as yet exhibited very little passion, urgency, or imagination,” and he went on to dismiss Wright’s work in just two words—“ploddingly sincere.”

After Dickey’s essay appeared, in the Sewanee Review, Wright wrote him a crude and defensive letter: “Since you both think and feel that my verses stink, it is your responsibility as well as your privilege to say so in print.” Yet he viewed Dickey’s critical approach as needlessly cruel. Students sometimes asked Wright for his opinion of their verse, he went on, and “when their verses were sentimental and inept, I believe that I have criticized them honestly and severely; however, I have never greeted a student by telling her to go fuck herself and shove her hideous poems up her ass.”

When Dickey replied sternly to this attack, though, Wright collapsed into contrition and self-reproach. “As I sit here,” he admitted, “I think I know why I was hurt. You simply said that I was not a poet. This remark of yours only confirmed what—obviously enough—is a central fear of mine, and which I have been deeply struggling to face for some time.” Wright’s doubts about his highly praised work were compounded by another jolt that he received in the very same week, when he read the first issue of Robert Bly’s new little magazine, The Fifties, whose inside front cover declared, “The editors of this magazine think that most of the poetry published in America today is too old-fashioned.” Just two days after his mea culpa to Dickey, Wright wrote to Bly, entirely renouncing his early work: “My book was dead. It could have been written by a dead man, if they have Corona typewriters in the grave.”

This double shock succeeded in winning Wright over to what Bly called, in an essay in the second issue of The Fifties, “the new poetry.” According to Bly, the “old style, with the iamb, its caesuras, its rhymes, its thousands of rhythms reminding us of other poems and other countries . . . is like a man speaking who gestures too much. . . . But in the new poetry, the contrary is true—there is no necessity in the form itself for continual gesture, by rhyme, etc.—therefore, if you raise your little finger once, slowly, it has tremendous meaning.”

This metaphor perfectly describes the technique of the first volume that Wright produced after this crisis: “The Branch Will Not Break,” published in 1963. The book contains much of Wright’s best writing, which indeed wagers everything on the effectiveness of small, dramatic gestures. The most celebrated and controversial example is “Lying in a Hammock at William Duffy’s Farm in Pine Island, Minnesota.”

The poem is a catalogue of meticulously observed natural details—“the bronze butterfly, / Asleep on the black trunk,” “The droppings of last year’s horses”—which concludes with a sudden, seemingly unjustified swerve: “A chicken hawk floats over, looking for home. / I have wasted my life.” The last line suggests how “deep image” poetry differs from the Imagism of the nineteen-tens: it is not the visual composition that matters to Wright but the way the visible world calls forth a mysterious inward response. And for Wright—as for Roethke, who declared that his poetry’s leaps of association “either . . . are imaginatively right or they’re not”—the link between things seen and things felt cannot be artificially prepared. He agreed with Bly’s dictum that “in the new style, where the tension and density of the emotion is everything, you have to, like a good gambler, agree to stake everything on one throw.”

Still more than Roethke, Wright is tempted to turn his poems’ aesthetic gamble into a moral test. As he wrote to his close friend Donald Hall, “Whatever a poet has been in the past, right now he is defined, to me, as a man who has both the power and the courage to see, and then, to show, the truth through words. If I’m a bad poet, that means a liar.” The literary results of this high-mindedness, however, were decidedly mixed. In his work of the nineteen-sixties, Wright’s determination “to show the truth” can give his voice a grave credibility, as in “Speak”: “To speak in a flat voice / Is all that I can do. / . . . I speak of flat defeat / In a flat voice.” But often in his later writing Wright strips from his poetry the very things that turn a personal experience into a shared work of art. In his quest to make his poetry authentic, he often descends to melodramatic reporting on his own emotions: “I feel lonesome, / And sick at heart, / Frightened, / And I don’t know / Why.” And he wards off any doubts about this style—his own or his readers’—with a kind of truculent earnestness:

This is not a poem. This is not an apology to the Muse. This is the cold-blooded plea of a homesick vampire To his brother and friend. If you do not care one way or another about The preceding lines, Please do not go on listening On any account of mine. Please leave the poem. Thank you.

But the job of the poet is to make the reader want to care—to awaken his sympathy, not extort it. The problem with Wright’s and Roethke’s poetics of sincerity is that it allows the poet to believe that right thinking is more important than good writing. In a 1961 essay, Wright made this denigration of artistry explicit: “It should be unnecessary to say that gentleness and courage in dealing with a subject matter very close to life . . . are primarily matters of personal character; and that, where the character is lacking, no amount of literary skill can substitute for it.” It is equally unnecessary to say that the reverse is also true: gentleness and courage, unfortunately perhaps, are unavailing without the colder cunning of the artist. Only when they combined both kinds of virtue did Roethke and Wright produce the poems by which they continue to live.