|

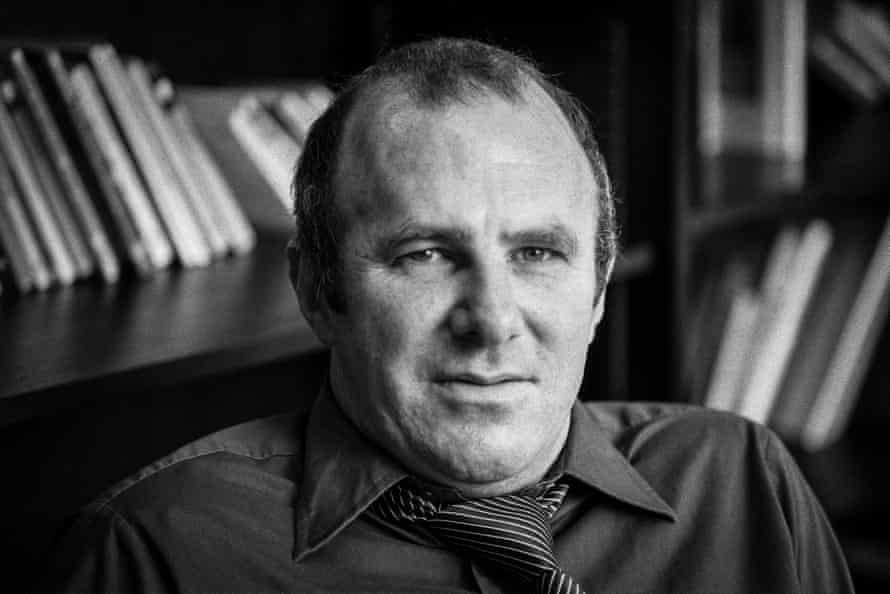

| Artist Claerwen James, aged three months, with father Clive. Photograph: Martin Pope |

'He returned to what he really was': Clive James's daughter on his poetic farewell

Artist Claerwen James on growing up with an extraordinary father – and how she bonded with him in his final months when they compiled an anthology of his favourite verse

Rachel CookeSunday 27 September 2020

Ten months before his death last year at the age of 80, Clive James underwent an eight-hour operation to remove a tumour on his face. Already very frail – he had been suffering from leukaemia for a decade – afterwards it took him almost a week to emerge fully into consciousness. “And even then, he was foggy,” says his daughter, the artist Claerwen James. “He couldn’t really see, which meant he couldn’t really read – and that had never been the case before.” For her father, this was not a small thing, whatever the size of his other problems. Words were his life raft.

But all was not lost. “The resource that he did have was the poetry he knew,” she says. “And he wanted to hear it. He’d recite a bit – sometimes, he’d have only a verse – and whoever was sitting with him would look up the next part, and read it to him. He loved this, and then he would often say a little about it. He’d tell us when he had first heard the poem, or point out which bit was most difficult to say.” Together, he and his readers got into a rhythm. “We started writing down all the poems he wanted to hear, and the relevant anecdotes, and in this way a manuscript began to emerge without him willing it.” If this felt at the time like a small miracle, it was also, in context, perfectly ordinary: “He was always working on something. There was literally never a moment when he wasn’t – and now, there was this. A pile of poems.”

At home again, the pile grew. “He went on adding to it. At first, he’d dictate. Then we got these enormous letters you stick on top of a computer keyboard, so he could type, if the font was blown up to the absolute max.” Clive had long thought of putting together an annotated anthology of poems “to get by heart and say aloud” – the idea had emanated, years before, from Claerwen’s mother, Prue Shaw – and now this notion became, through the haze of illness, a reality. He called it The Fire of Joy – the French expression feu de joie refers to a military celebration when a regiment’s riflemen fire one shot after another in close succession – and he would go on to finish it only a month before his death last November. Dedicated, in valedictory fashion, “to the next generation”, its lovely, consolatory epigraph is from Homer: “The race of men/Is like the generations of the leaves – /They fall in autumn to return in spring.”

For both father and daughter, this last project was a blessing, in the most complete sense of that word. In the last years of his life, Clive lived in the house adjoining Claerwen’s in Cambridge, a permanently open door connecting her kitchen to his sitting room, a realm that became his entire world at the end. (This is where we are now: Claerwen, my friend of more than 25 years, at one side of the long table at which he worked, and me on the other, the pair of us surrounded by his books, pictures and photographs.) And there, they made the book together. Even while he slept – he could work for only an hour a time – Claerwen was painting designs for its cover, one eye on her brush, the other on him. “The thing I brought to it was my ignorance,” she says, with a laugh. “But I think my ignorance was important! I was receptive. I had nothing, except my enthusiasm. The book isn’t for the poetry aficionado necessarily. It’s just him, picking the bits he loves best and talking about them in a straightforward, simple way – and I was helpful with that because I felt the things he thought were completely obvious were not at all completely obvious.

“The book is about how poetry sounds; the fact that it’s supposed to be said aloud. There were people who sat with him who were good at reading poetry, and knew a lot about it. But sometimes, it was me, and I don’t know anything about poetry, and I prefer not to read poetry aloud if I can possibly help it.” She pulls a face. “I find it embarrassing when other people do it, and poetry generally … I’m mostly a prose reader. Poetry feels like you have to be initiated, sufficiently romantic, and prepared to deal with the obscure. But then he would talk about it, and I would suddenly feel: ‘Oh, this isn’t a closed book, after all.’” Her father gave her rules when it came to reading aloud, encouraging commandments that can now be found at the beginning of The Fire of Joy. “They were really basic. Don’t go too fast. Don’t get ahead of yourself. Pause at the end of a line. If it’s a good poem, he thought, the rhythm somehow gives you the meaning: it springs out. I found this to be true when I read to him, and that discovery was incredibly moving to me.”

The book was a place in which they could get lost, just for a little while – though it was, for Clive, much more than a distraction. “It was partly that he needed to be making something. But also, he would have felt he had no identity if he hadn’t been. Doing this, he was still him.” What did he feel about her part in it? “Oh, I don’t know! I’ll cry if you ask me that. It was … lovely to do it together. It feels right now, because it is such an emanation of that time. It’s difficult, dying. It’s really hard. To the extent that it’s possible, we travelled that road together.” To be with someone in their last months and weeks is, she believes, to be given an immense gift. “It is a privilege, an enormous one. He was sort of incandescent, really. It felt like he had passed through something. At the end, you’ve passed through all the lies you tell yourself about what life is about, and what you might accomplish. You know what’s coming. He just appreciated everything in this astonishing way, and because I saw everything through his eyes, it was as though we were feeling the same things.”

I travelled to Cambridge to interview Clive a few weeks before he died. What struck me then, though he still had me collapsing into laughter, was that he was a better listener than of old. “Yes, listening was not his primary quality,” Claerwen says, drily. But she agrees. At the end, it was as if time had expanded, even as it was running out. “His world had shrunk to this room, and that terrace,” she says, looking towards the balcony. “He never went anywhere, he saw almost nobody, he could eat almost nothing – and yet, every aspect of his life was filled with meaning. The fact that there was an apple on that tree; whether it was rainy or sunny. Everything was extraordinary.” It was this sense of repletion – the limitless wonder to be found in the everyday – that made looking after him a privilege. “In our society, the fact that we put away the things we’re afraid of, so as not to look at them – and with a story about how it’s kinder, better, for professionals to do this [work for us]. I think it’s wrong. You don’t understand the shape of a life, if you don’t see the end of it.”

The shape of Clive James’s life was unlikely: for myriad reasons, in my mind’s eye, I can’t help but picture it as a boomerang. His Australian childhood was marked by loss after his father, Albert, who had survived a Japanese PoW camp during the war, was killed when the plane bringing him home crashed in Manila Bay – and it was this event that would go on to define his life; to create it, in a way. “It wasn’t only that he wanted to be happy, to make the most of life,” says Claerwen. “It was that he thought it was his absolute responsibility to do so; a duty. He’d been given something; someone else had sacrificed something – an entire generation had sacrificed something – so that he, and people like him, could live their lives.” The fact of his having been born in 1939 gave him a sense of proportion that stayed with him all his life. “He would think: this is bad; this is complicated and fraught with argument. But it’s also good, because we are in the realm of the lucky. He was not a despondent person, ever. He didn’t want to die. He was sad to go. But those were positive emotions. He wasn’t morbid. He never thought: poor me.”

The public perception of Clive James generally divides into two: there are those who think of him as a brilliant journalist – as the funniest critic ever to have written about television (a job he did at the Observer for 10 years) – and the author of a series of hilarious autobiographies (Unreliable Memoirs, Falling Towards England, May Week Was in June); and then there are those who remember him mostly as the presenter of prime-time chat shows, of series about weird foreign television, and of travelogues in which he goofed around in places like Las Vegas. But there was, and is, a third James, the author of books of poetry, of four novels, of high-minded essays and reviews, and even of a translation of The Divine Comedy (Prue Shaw is a Dante scholar; he once said that he never gave up trying to impress her). It was this third persona that he occupied, almost exclusively, in the last decade of his life, and it brought him full circle: literature was his first love, both in school and, later, at university in Cambridge where, having completed his second degree, he embarked on, but never completed, a Shelley PhD.

Poetry was injected into his veins at his school in Hurstville, Sydney, whose “supposedly playful regime” was, he writes in the introduction to The Fire of Joy, symbolised by a rule that every pupil had to recite a memorised poem before he was allowed to go home: “a fantastic combination of Parnassus and a maximum security prison”. At the University of Sydney, he met “actual living poets” during his first week – they were fellow students, of course – and by the second week, he, too, was wearing a long scarf and brothel-creepers, and carrying an armful of books by Ezra Pound: “I had decided to become a poet, although there was nothing bold about this decision, as it was already clear, even to me, that I was useless for anything else.” Claerwen remembers her parents reciting poetry to each other “on holiday, after dinner, walking along the beach, each of them supplying the lines the other couldn’t remember. Poetry was demotic in Australia – everyone knew The Man from Snowy River [by the Australian bush poet Banjo Paterson] – and it was also, then, where it was at. It was sexy.”

It’s this version of her father, she feels, that was the authentic Clive: the reader, and the romantic. “He was insanely romantic. I mean, absurdly so. It was that thing of the armour plating of being funny to protect you from the fact that you absolutely wear your heart on your sleeve.” And it was this Clive who was restored to those who loved him towards the end of his life. “He had so many miraculous escapes: he would get to the end of his treatment, and they would invent something new, he would try it, and it would stop him getting worse for a bit. But in my more mystical moments, when I’m trying to make meaning out of this, I feel he was … purified in some way – and I think he had quite a long way to go! I don’t think it’s good for people to be famous. I think it’s really bad for them. I think it makes them mad.” So his illness was, paradoxically, a recovery period, like rehab or something? “Yes, I do feel that. That he was returning to what he really was.” Did being ill give him permission to stop being the more famous Clive James? “Yes. It gave him permission to watch TV and write poetry, which is what he really liked doing.”

Among the poems he loved best that are in The Fire of Joy are verses by Keats (Ode on Melancholy), Shelley (Ozymandias), Yeats (An Irish Airman Foresees His Death); Clive thought Yeats was a “fool and buffoon in later life”, but a great, great poet) and his beloved Larkin (An Arundel Tomb). But there are surprises, too; obscurities. Wild Peaches by the high-born bluestocking American poet Elinor Wylie (“her technique was perfection”) and Craftsmen by Vita Sackville-West, which begins, unimprovably, with the line: “All craftsmen share a knowledge. They have held/ reality down fluttering to a bench” (as Clive writes, whatever you may feel otherwise about Sackville-West, the author of a poem “as good as this can never die”). But the one that he and Claerwen would, together, come back to most often was Dover Beach by Matthew Arnold. “I’d never read it before,” she says. “It really knocked me over. I was reading it to him, in this state of great anxiety, and we got to ‘its melancholy, long, withdrawing roar’… it’s an out-of-body experience. We were both quietly mopping up afterwards.”

Clive was not, perhaps, the easiest, most straightforward of dads. His ego was vigorously healthy. He could be selfish. There was bad male behaviour of the usual kind. But she would not have had any other sort of father. She will take his flaws, because they cannot be separated from his vividness: “If you’re robust enough to cope with the fallout, which can be considerable, your horizons are so much bigger. He was so much fun to be around. Everything was interesting. Everything was material. ‘Hmm, I’ll learn Arabic,’ he’d say. ‘Why not?’”

He widened her world. He made her feel she could do anything – and she duly did, swerving dramatically at one point in her life from science to art. (When she and I first met, she was a molecular biologist. But having finished her PhD, she got a place at the Slade School of Fine Art, where she graduated with a first, and suffice to say, I could not possibly afford one of her paintings now.) “My mother was always there, providing good sense and stability,” she says. “But my sense of what the world was, is, and can be – of what a person can accomplish, and in particular of what a person can teach themselves through the simple act of application – is so enormous because of my father, and I’m so grateful for it.” She smiles. “When I discover something new, he’s still the person I want to talk to about it.”

No comments:

Post a Comment