|

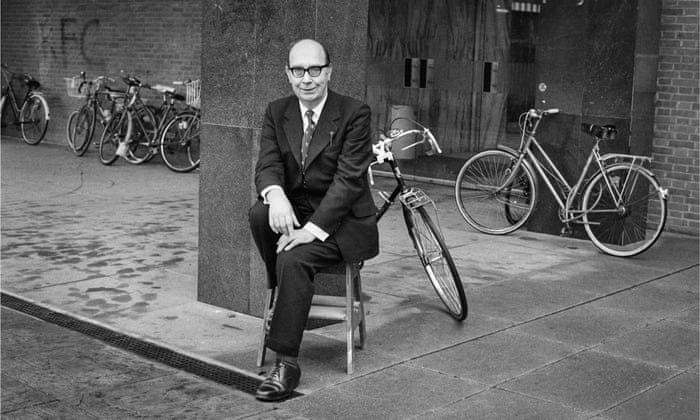

| Clive James in 1977 at the offices of the Observer, where he worked as television critic. |

Clive James: the last interview

Two months before his death, the broadcaster, poet and critic spoke about his own mortality

Rachel Cooke

Sunday 1 December 2019

J

ournalists shouldn’t interview people they know, or even (I think) acquaintances with whom they’re friendly. But in September I broke this rule, and went to Cambridge to talk to Clive James about his latest book.

The day before, I’d taken a call from his daughter, Claerwen James, the artist and my friend of more than 25 years. Clive was soon to publish a short book about Philip Larkin. He was pleased with it, and wanted to tell people about it. But he was also too ill, by this point, to see a stranger. Would I come? It would mean so much to him. I told her that I would.

I want to be clear. It is Claerwen who was, and is, my friend, not Clive. But still, he was a big and beloved figure in my life, and not only because she and I could spend hours at a time talking about our fathers in particular, and men in general. When I first met him, I was 25 and miserably toiling as a trainee in a Fleet Street newsroom. I knew no one, and nothing, and I was very shy, and thanks to these things – and the fact that he was a genius – I was a bit intimidated by him at first. Nevertheless, in those early years, he influenced me in all sorts of small but vital ways. I have a strong memory of an afternoon some time in about 1998. Claerwen and I walked into a room to find Clive listening to Joan Sutherland singing Bellini’s opera Norma. He was in a state that seemed to me to be close to sexual ecstasy: legs apart, head thrown back, a look of pure bliss on his face. I knew nothing of opera then, but as he translated her words for us – he sprang out of his chair to do this – I thought to myself: I’ll have what he’s having, thanks. That recording of Norma was the first opera I ever owned on CD, bought that very week. Clive’s enthusiasm, as bright and as powerful as a Klieg light, could make you want to read, listen to, watch or look at almost anything.

He was – this has already been said – very, very clever and very, very funny; he had a way of making you see that something could be both ridiculous and magnificent, and ever since I first learned this from him, I’ve always borne it in mind. He had, too, a sybaritic side that I adored. He could squeeze such pleasure from things. I’ve never seen anyone drink a bottle of Jacob’s Creek with so much enjoyment as him; it might as well have been Château Lafite in his glass. I thought of him, always, as deeply generous.

He noticed you, and what you were up to. Whenever, in later years, he was trying to get me to come to one of his book launches – I didn’t need much persuading – he would send me such sweetly beseeching emails. His “dazzlement division” needed me, he would insist. A certain kind of flirtation, like a certain kind of teasing, is a form of kindness, and for all that I did not take these messages too seriously (he was like this with everyone), that was how I received them: as kindnesses.

What I loved most of all, though, was to see him make Claerwen laugh. It’s my strongly held belief that a man who can make his own daughter – who is almost bound to be, however loving, a sceptic so far as her male parent goes – collapse into laughter is basically doing all right.

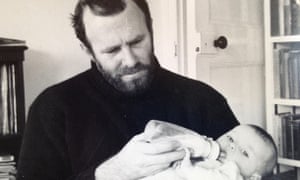

|

| James with his daughter Claerwen, in a photograph taken by her mother, Prue Shaw. Photograph: Courtesy of Claerwen James |

On that day in September, he made us both laugh a lot. When I arrived, he was sitting in the thin autumn sunshine on the little balcony off his sitting room (a balcony that once overlooked the famous maple tree that was the subject of one of his late poems). He had grown a beard, and that, and his happy wave when I came in, made me think of Robinson Crusoe. I was shocked by the way his cancer had ravaged his face – contrary to reports last week, it wasn’t his leukaemia that killed him, but a metastatic squamous cell carcinoma; in other words, it was the Australian sunshine he absorbed in his youth that did for him in the end – but his eyes were refulgent, and he was so full of grace, and so intact in every other way. Somehow, he was the very essence of himself. It was heart-stirring to see, an almost numinous thing, though I knew he didn’t believe in God.

Larkin had always been a bond between him, Claerwen and me: we just think he is the Man. The book Somewhere Becoming Rain is a gathering together of everything Clive ever wrote about Larkin. It was Claerwen’s idea; she designed the cover, and it’s dedicated to her. On that day, we talked about Larkin first.

When he grew tired, we gossiped a bit. He and Claerwen were looking for a new box set to devour, and I recommended Succession. (She told me later how much he liked it.) Finally, we looked at a draft of The Fire of Joy, which will be published next year and is a collection of “roughly 80 poems to get by heart and say aloud”.

As I turned its pages, I was struck, all over again, by the astonishing range of his reading. Here were Auden and Keats and Wyatt. But here, too, were poets I’d never heard of. Clive read (in multiple languages) like his life depended on it – and perhaps it did, in a way. Words, to him, were as necessary as water. What follows is part of our conversation. At the time, I knew it would be our last, and yet it was so easy. Clive loved to have an audience – and I loved to listen.

|

| Philip Larkin, 1979. Photograph: Jane Bown |

Can you remember when you read Larkin for the first time?

The answer is yes, yes, yes – and yes. It was the cold winter of 1964. My landlord, a young publisher, said that if I really wanted to catch up with modern English poetry, I should read Philip Larkin. So I read The Less Deceived. Although I like to think that I brought a certain receptivity to the party – I was his ideal reader – I was knocked out straight away.

How did he make you feel?

First of all, the spoken rhythms were so wonderful. I still think he’s the tops in that way. Second, I knew exactly what the poems meant – and that’s what staggers me, still, about him. There can’t be many poets in any language who communicate with their readers on such a basic level. I went quietly mad for him.

I’d just arrived from Australia, and I wanted to tell him these things, so I wrote to him. I don’t know what drove me to be so crazy as to think he would have time to read a letter from me, let alone to answer it, which he did. Jesus Christ. It [my fandom] was akin to love. But [if you’re the poet] you don’t want too many lovers turning up.

By the time his last collection, High Windows, was published in 1974, you were in a position to review it. Was that a big deal for you?

Yes. The feeling was: this is history, and it’s happening to me. It’s an unbeatable thing, writing about art. It’s heaven.

Did it sadden you, what happened to Larkin’s reputation in the period after his letters came out in 1992, and his biography the following year? [Larkin stood accused of racism and bad behaviour to women.]

Yes. I could talk about this for ever, which is a bad sign. There were faculty members here in Cambridge saying we shouldn’t read Larkin. What the fuck does that mean? Who else are you recommending we don’t read?

My reaction was, and is, people shouldn’t do this. It’s scary. If you are sensitive to language at all, I can’t see how you can’t admire him on some level. The connection between poetry and morality somehow got firmly established in the English university system through [the critic] F R Leavis; poetry came to have to do with virtue.

Personally, I’ve always thought that English literary history suffers from its shortage of villains. It needs more bastards in the [John Wilmot, Earl of] Rochester mould. But that said, while Larkin shouldn’t have said those things, he was [outwardly] the model of a gentleman. It’s impossible to imagine him being rude, or even sharp to someone.

I think there are various big and obvious reasons why some people wanted to diminish him. One would be his enviable reputation. Another would be the fact that he just didn’t cooperate. He stayed in Hull. London literary life wasn’t for him.

That life was for you, though, wasn’t it?

Ha, yes. I enjoyed it, the whole business. The argy-bargy. The tangle. My rivals, even.

And Larkin’s poems sail on, don’t they?

Yes, and that’s the loudest thing to say. Though it could have been a near-run thing, they won through.

If we were on a desert island, what Larkin poems would we want?

First of all, I’d be trying to attract your attention. So it would be the romantic ones. But … we’re on a desert island! I’d already have your attention.

No, there are so many. I’d have The Whitsun Weddings, Aubade, Church Going, Mr Bleaney, Dockery and Son, To the Sea, An Arundel Tomb, At Grass – it’s fabulous – Next, Please. His range of evocation is unmatched since metaphysical times, and he has – people forget this – such a feeling for the countryside, puttering along in his very unpowerful car.

What about death? Larkin is preoccupied with it, and I wonder what you feel about that, now.

My family was marked by tragedy [James’s father, a prisoner of war in Japan, was later killed when a plane bringing POWs home crashed in Manila Bay]. But I, personally, have been marked by all the blessings. I’m giving thanks for life now, which isn’t much like despair, is it?

But Larkin was different. He knew it would end in silence, and he was afraid of the silence. He didn’t like the idea of not being here. I’m not like that – and my death might come as a relief to quite a few people. I’d rather like it not to hurt, that’s all.

Will you write another book?

Suppose I did another volume of memoirs…

Would you like to?

Yes, but I don’t think I have the energy. I’ve been hit in the face by a cricket bat at 1,000 miles an hour. I think the last round-up is here. But that’s OK. It would be bad manners to complain. I’ve had a lucky life, and I’m grateful for it.

No comments:

Post a Comment