|

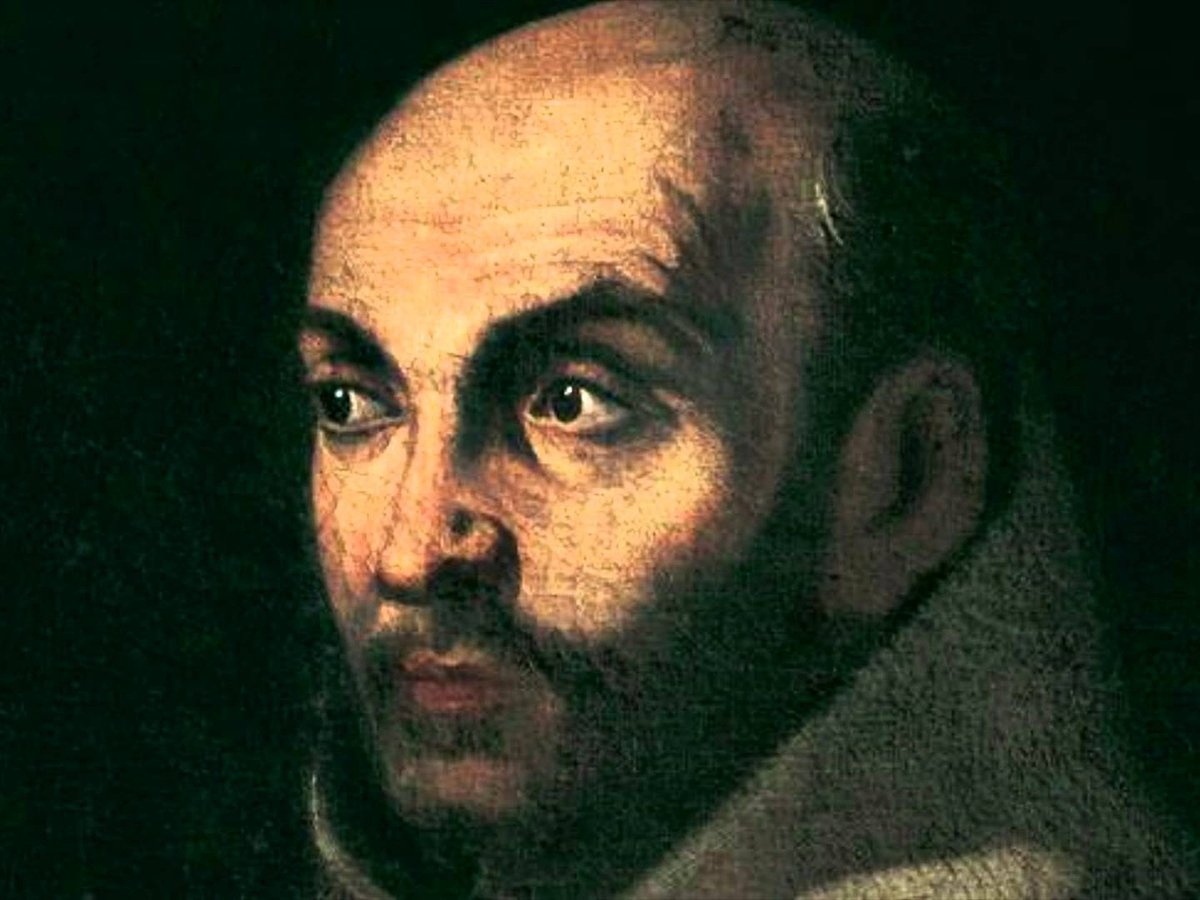

| San Juan de la Cruz |

FATHER CHARLES NEALE: AMERICAN JESUIT, "ADOPTED" CARMELITE AND THE FIRST ENGLISH TRANSLATOR OF SAN JUAN DE LA CRUZ?

Daniel Hanna

Department of Foreign Languages

Towson University

Charles Neale and the Carmelite Order

The life of Charles Neale was intended to follow a carefully prescribed path from America to Europe and back. Sent as a young boy from his native Maryland to the College of Saint Omer in French Flanders, he was expected to attend seminary there and return to America a Jesuit priest. Neale crossed the Atlantic in 1760, at the age of nine, and traveled to Saint Omer’s to study for the priesthood with the end goal of returning home to support the Catholic faith, and in particular the Jesuit mission, in his native land.(1) But not long after Neale’s arrival in Flanders, events took a series of unexpected turns that would lead him to live not among Jesuits, but among Carmelite nuns, and to produce what appears to be the earliest known English-language translation of the famous Cántico espiritual of San Juan de la Cruz.

Neale had been at Saint Omer’s less than two years when the French Parliament’s decree of 1762 forbade the Jesuits to operate in France and French territories and ordered the closing of their schools. It would be another two years before the Jesuits were finally expelled from Saint Omer’s, but expelled they were, and in 1764 the thirteen-year-old Charles Neale, along with his professors and more than one hundred other students, managed to flee French territory and reassemble in Bruges in what the Catholic Encyclopedia describes as “one of the most dramatic adventures in the history of any school.”(2) In Bruges Neale was able to continue his studies and in 1771, a few weeks before his twentieth birthday, he entered the Jesuit novitiate in Ghent.(3)

But just as the anti-Jesuit movement had reached Saint Omer’s a decade earlier, it would soon reach Ghent, and indeed the rest of the Catholic world, when in 1773 the Society of Jesus was universally suppressed by orders from Rome. The Dominus ad Redemptor brief ordering the suppression of the Society, which came just days before Neale was to make his first vows, halted his career as a Jesuit. Although Neale was able to continue his study toward the priesthood in Liège and had been ordained a diocesan priest by 1780, his original ambition of becoming a Jesuit had seemingly been thwarted for good.(4) It was around this time that Neale was given the opportunity to become the director of the Carmelite convent of Saint Joseph and Saint Teresa in Antwerp. At first Neale seems to have resisted the appointment. As Charles Warren Currier wrote in Carmel in America, the then twenty-nine year old Neale “modestly declined to accept the invitation, excusing himself on the score of his youth and inexperience.” In the end, though, Neale was persuaded, and it seems to have been family ties that made the difference: Mary Margaret Brent (in religion Mary Margaret of the Angels), the superior of the convent, was Neale’s cousin, and like him had gone from her native Maryland to Europe to pursue a Catholic vocation. After what Currier described as “a lengthy correspondence on the subject” instigated by Mary Margaret to convince Neale to take the position, “her perseverance ” and Neale accepted.(5) In October 1780 Neale arrived in Antwerp to assume the direction of the convent, and with that he began what turned out to be a lifelong association with the Carmelite Order.

For ten years, Neale served the Carmelites of Antwerp as director and confessor. In the course of these years, Neale necessarily exercised an influence on the Carmelites under his care, but the reverse was also true, as his cousin Mary Margaret and the other Carmelite women of Antwerp shared their ideas and way of life with him. As Constance Fitzgerald writes in The Carmelite Adventure, during this time Neale would “absorb Mary Margaret Brent’s perception of Carmelite life along with her dreams and plans.”(6) Among these dreams and plans was a project that aligned closely with the blueprint that had originally been drawn for Charles Neale’s life: an eventual return to America.

By the late 1780s political and religious conditions in the newly founded United States made possible the idea of establishing a Catholic convent there, and a plan was set in motion to found a Carmelite convent for women in the very place that Charles Neale and Mary Margaret Brent had called home before traveling to Europe: Charles County, in the state of Maryland. The project had strong support and met with the approval of the authorities concerned, and on April 19, 1790, Charles Neale and a group of four Carmelite women set off from Flanders for the United States. Their journey would last over two months and would culminate in the foundation of the Carmelite convent of Port Tobacco, Maryland, using land and funds that Neale himself donated for its establishment.(7) Thus, Charles Neale would make his return voyage to America not as a Jesuit as originally planned but rather as a leader and companion of Carmelite women.

Charles Neale and the Carmelite Poetic Tradition

Among the aspects of Carmelite life to which Charles Neale was exposed during his time in Antwerp and America was the practice of composing verses celebrating special occasions, honoring members of the religious community and in some cases expressing intimate spiritual experiences. This tradition can be traced back to the reformer of the Carmelite Order, Santa Teresa de Jesús, who in 16th-century Spain founded the branch of Carmel to which the Carmelites of Antwerp, and later America, would belong. Santa Teresa felt strongly that the rigors of convent life should be balanced by moments of joyful celebration, and she encouraged her fellow Carmelites to compose verses and share them with one another, often singing them at daily recreations.(8)

Charles Neale appears to have been a participant in the practice of composing and sharing poems, which had been part of Carmelite life since the time of Santa Teresa. As evidence of this, poems composed by Neale and by the Carmelite women with whom he lived in Antwerp and America can be found in manuscripts now housed in the archives of the Carmelite convent of Baltimore, Maryland. Sister Clare Joseph, who along with Neale had made the voyage from Europe to America to found the Port Tobacco convent, celebrated Neale’s journey to Europe and return to America in one of her poems:

No boist’rous waves, no ocean wide could stay

His eager pursuit of fair virtue’s way; But launching forth across the briny main, His native soil he quits, to bless again. [...] His noble heart, with zeal of souls now burns, And thirsting for his native soil returns; With four of Carmel’s humble virgin train, He crosses o’er th’Atlantic’s briny main. [...] Deign, cherished pastor of this flock t’accept These rhymes as tokens of our true respect, And for the want of Virgil, Homer’s skill, Receive, Dear Father, our sincere good will.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9513, 13-14)

|

Charles Neale in turn composed at least one poem of his own honoring Clare Joseph, on the occasion of her “jubilee” in 1797, when the convent celebrated her twenty-fifth year as a Carmelite nun:

Ye virgins of Fair Carmel’s grove

Unite your voices, sing with glee; With presents testify your love: It is your mother’s jubilee. [...] O Lord forgive us all that’s past: Grant her with us long to remain, With her may we breathe out our last And mount to Heaven in her train.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9514, 150)

|

As poems of mutual admiration, these compositions show the close friendship that existed between Charles Neale and his Carmelite companions, first in Europe and later in America, where Neale continued to live with and serve as confessor to the Carmelites in their new home. These poems also indicate that Neale himself entered into the Carmelite verse tradition, thus maintaining a practice instigated centuries earlier by Santa Teresa de Jesús at the time of her reform of the Carmelite Order. But if Charles Neale was devoted to the Carmelites he led and accompanied in his own time and, by extension, to their “founding mother,” Santa Teresa de Jesús, he also appears to have had a strong admiration for another central figure in Carmelite history: San Juan de la Cruz, the Carmelite friar who aided Santa Teresa in her reforms and who is remembered today as Carmel’s greatest poet, and indeed one of the greatest poets in the Spanish language.

Neale’s Translation of the Cántico espiritual

In 1577 Fray Juan de la Cruz was called before a tribunal of his fellow Carmelites who were opposed to the reforms being proposed by Teresa de Jesús, reforms that Juan supported and in which he was an active participant. The tribunal demanded that he retract his support for the Teresian reforms, but Fray Juan was steadfast in his loyalty to Teresa and refused. For his insubordination the tribunal sentenced Juan to imprisonment in the city of Toledo, a cruel punishment to be sure, but one that would result in the creation of one of the masterpieces of Spanish literature. As Antonio T. de Nicolás writes, “It was in this jail, during the summer of 1577, that San Juan de la Cruz wrote the poetry that made him famous.”(9) In this prison cell, Fray Juan began the composition of the poem that became known as the Cántico espiritual, an intimate account of the meeting between God and the soul, reminiscent of the allegorical Song of Songs. While San Juan went on to produce other writings, it is above all for his Cántico espiritual that he is known and celebrated.

The first Spanish edition of San Juan’s Obras was published in 1618 in Alcalá de Henares, Spain, but interestingly the Cántico, by this time well recognized as one of San Juan’s most important texts, was omitted from the Alcalá edition. In The Mystic Fable, Michel de Certeau speculates that the Cántico was omitted because of its “audacity,” expressing as it does divine love in seemingly human terms, and other accounts have it that the Carmelite Ana de Jesús, to whom Juan had dedicated the poem, forbade its publication in the Alcalá edition.(10) Whatever the case, the Cántico appeared in print for the first time soon after the Alcalá edition, in a French translation published in 1622 by René Gaultier, and the first publication of the Spanish original followed not long after in a 1627 edition published in Brussels.

In the course of the 17th and 18th centuries the Cántico and San Juan’s other writings were published in an increasing variety of European languages, including new translations to French and a translation to Italian, but it would not be until the latter half of the 19th century that an English-language edition of San Juan’s works would appear, when David Lewis published his translation in London in 1864. But decades before Lewis’s translation, as Charles Neale was becoming increasingly steeped in the ways of Teresian Carmel, the Cántico espiritual caught the interest of this American who had aspired to the Jesuit priesthood but who was now an “adopted” Carmelite, a man who had found a spiritual family thanks in part to the persuasions of his worldly family and who had played an essential role in bringing Carmel to America.

Among the extant papers of Charles Neale there appears to be no specific mention of his interest in the Cántico espiritual, but what does exist – a full-length manuscript translation to English of the forty stanzas of the Cántico, carefully rendered in six-line stanzas of octosyllabic rhyming verse, undated but clearly attributed to Neale – is evidence that at some stage in the spiritual life that he shared with the Carmelites of Antwerp and America, Charles Neale immersed himself in San Juan’s poetry in a way that offers further proof, if any were needed, of his devotion to Carmel.(11)

To say that Neale’s translation of the Cántico is a faithful one is at once completely true and too concise a description. First, Neale’s rendering of the poem, composed as it is in rhyming verse and consistent meter, fully honors the Teresian tradition of Carmelite poetry, which had its roots in the popular song of 16th-century Spain and, from Teresa and Juan’s time to the time of American Carmel, always maintained what might be considered its “musical” aspects.(12) Rhyme and meter were essential to the function and character of Carmelite poetry, and Neale’s translation preserves both of these elements of San Juan’s original. One might observe at this point that rhyme and consistent meter were features of nearly all poetry in the 16th to 19th centuries (and earlier) and as such a rhyming, metered translation was to be expected. But a comparison of the approach taken by Neale to that taken decades later by David Lewis is useful in understanding Neale’s adherence to Carmelite tradition. Lewis’s translation carefully reproduces the sense of each verse of San Juan’s original but leaves rhyme and meter behind, as can be seen in Lewis’s first stanza, given here with San Juan’s original:

¿Adónde te escondiste,

Amado, y me dexaste con gemido? Como el ciervo huyste, aviéndome herido; salí tras ti clamando y eras ydo.(13)

Where hast Thou hidden Thyself?

Why hast Thou forsaken me in my groaning, O my Beloved? Thou didst fly like the hart, away, When Thou hadst wounded me, I ran after Thee, crying; but Thou wert gone.(14) |

The interest of a translation such as Lewis’s, which aims to adhere as closely as possible to the terms and meaning of the original, is evident. For the first published rendering of San Juan’s complete works in English, precision could perhaps justifiably have been given priority over aesthetics. But for Charles Neale, who lived and worked inside Carmel for most of his life, the aesthetic, “musical” qualities of the poem would have been essential. In preserving these aspects of San Juan’s original poem, Neale likely strove to be faithful not only to the text of one particular Carmelite poem, but also to the spirit and character of Carmelite poetry generally, in which theme and meaning could not be divorced from rhyme and meter.

This said, a second feature of Neale’s translation of the Cántico that establishes it as a faithful one is precisely its remarkable thematic and lexical fidelity to the original. While necessarily not as exact as Lewis’ translation, given the extreme difficulty of translating rhyming metered verse into rhyming metered verse, Neale’s rendition consistently manages to preserve the key thematic and lexical aspects of San Juan’s original, all within the aesthetic framework that Carmelite poetry demanded. Below is Neale’s translation of the opening stanzas of the poem with San Juan’s original:

¿Adónde te escondiste,

Amado, y me dexaste con gemido? Como el ciervo huyste, aviéndome herido; salí tras ti clamando y eras ydo.

Pastores, los que fuerdes

allá por las majadas al otero, si por ventura vierdes aquél que yo más quiero, dezidle que adolezco, peno y muero.

Buscando mis amores

yré por esos montes y riberas; ni cogeré las flores, ni temeré las fieras, y passaré los fuertes y fronteras.(15)

Where hast my fair one hid his face,

Regardless of my piteous case? He gave the wound, then from my bed Swift as the hunted stag he fled. I sallied forth, but all in vain. Nor speed, nor cries could Him detain.

O! ye who scan yon mountain high,

That hides its summit in the sky, O shepherds such you seem to be, If ye my love perchance should see, O tell him that his wounded Dove Grows sick and faints and dies with love.

In search of Him, for whom I sigh,

I’ll pass those floods and mountains high, No blooming flow’r my steps shall stay, No savage beast my soul dismay, Strong forts and frontiers I defy. I’ll find my dear one or I’ll die.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9514, 156)

|

As a side-by-side comparison of the two versions shows, with a minimum of thematic and lexical invention, Neale faithfully renders San Juan’s message while maintaining a consistent aesthetic structure in terms of rhyme and meter. And with few exceptions, Neale maintains this “double fidelity” for the entirety of the translation (given in full in the appendix to this article).(16)

At the same time, one of the most fascinating aspects of Neale’s translation is that it is precisely in the few moments in which he clearly deviates from San Juan’s theme and lexicon that he shows himself to be faithful to Carmel and Carmelite poetry in yet a third way. In the seventh stanza of the poem, Neale translates as follows:

Y todos quantos vagan

de ti me van mil gracias refiriendo, y todos más me llagan, Y déxame muriendo un no sé qué, que quedan balbuziendo.(17)

For every one that speaks to me,

Relates a thousand claims of Thee, But whilst those charms their tongues display, And fain a some-thing else would say, Transpierc’d anew, I know not why, In tort’ring extasy I’ll die.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9514, 157)

|

While the degree of Neale’s lexical and thematic invention in this stanza is slight, it is nonetheless highly significant, and points to the source upon which the translator drew when complementing San Juan’s original text. Anyone who has seen Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s famous sculpture L’Estasi di Santa Teresa will see the reflection of that image in Neale’s verse, in which the soul is not merely wounded as in San Juan’s me llagan, but transpierc’d, and not only dies as in San Juan’s déxame muriendo, but dies in tort’ring extasy. Bernini, of course, invented neither the theme of his sculpture nor the key word in its title; these come straight from Teresa’s own writings, both prose and poetry. In her autobiographical Libro de la vida, Teresa wrote of her experiences of union with God:

Querría saber declarar con el favor de Dios la diferencia que hay de unión a arrobamiento u elevamiento, u vuelo que llaman de espíritu u arrebatamiento, que todo es uno. Digo que estos diferentes nombres todo es una cosa, y también se llama éstasi.(18)

Here Teresa uses the word éstasi to describe the soul’s ascent to union with God; in another passage of her Libro de la vida she recounts how she felt the presence of God in the form of a flaming arrow shot into her heart by an angel:

Víale en las manos un dardo de oro largo, y al fin de el hierro me parecía tener un poco de fuego; éste me parecía meter por el corazón algunas veces y que me llegava a las entrañas. Al sacarle, me parecía las llevava consigo, y me dejava toda abrasada en amor grande de Dios.(19)

Teresa also recalled this episode in her poem “Mi amado para mí”:

Hiróme con una flecha

Enherbolada de amor Y mi alma quedó hecha Una con su criador; Ya no quiero otro amor, Pues a mi dios me he entregado Y mi Amado para mí Y yo soy para mi Amado.(20) |

Indeed, often when Neale appears to be engaging in lexical and thematic invention, he is not inventing at all; he is merely turning to another source which, thanks to his years among the Carmelites, he likely knew as well as he knew San Juan: Santa Teresa. This is further evident in the eighth, ninth and tenth stanzas of the poem, where Neale translates as follows:

Mas, ¿cómo perseveras,

¡o vida!, no viviendo donde vives, y haziendo por que mueras, las flechas que recives de lo que del Amado en ti concives?

¿Por qué, pues, as llagado

aqueste coraçón no le sanaste? Y, pues me le as robado, ¿por qué assí le dexaste, y no tomas el robo que robaste?

Apaga mis enojos,

pues que ninguno basta a deshacellos, y véante mis ojos, pues eres lumbre dellos, y sólo para ti quiero tenellos.(21)

How canst thou soul endure this strife?

Why livs’t thou where there is no life? With softest touches, sweetest sighs, With sparkling, love-infusing eyes, Thy spouse has stol’n they heart away, And canst thou be content to stay.

O! to my bleeding heart apply

A remedy, and let me die: ‘Tis strange, ‘tis hard, o ‘tis unkind To leave one desolate behind: Why not in triumph bear away Thy wounded, fainting, dying prey?

O! sooth my anguish let me live,

The life that Thou alone canst give! O now my love without disguise, Bless with thy beauteous light my eyes, Awake to thee, this joy, this pride, And shut to ev’ry thing beside.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9514, 157)

|

Where San Juan, in stanza eight, establishes the life-death duality no viviendo donde vives/Y haziendo por que mueras and then leaves this theme aside in stanzas nine and ten, Neale thematizes life and death in all three of these stanzas, particularly in stanzas nine and ten where San Juan makes no mention of them. But this insistence on the theme of simultaneous life and death, like the arrow and the ecstasy, is not of Neale’s invention. It is, however, the very foundation of Teresa’s most famous poem, “Muero porque no muero”:

Vivo sin vivir en mí,

Y de tal manera espero, Que muero porque no muero.

Vivo ya fuera de mí,

Después que muero de amor, Porque vivo en en señor, Que me quiso para sí. Cuando el corazón le di Puso en él este letrero: Que muero porque no muero.(22) |

Neale’s threefold fidelity to Carmelite tradition and sources again shows itself in the twenty-third stanza of the poem, where Neale translates:

En solo aquel cabello

que en mi cuello volar consideraste, mirástele en mi cuello y en él presso quedaste, y en uno de mis ojos te llagaste.(23)

With that same hair, whose magic power

The captive made yonder bower, As graceful on my neck behind, It play’d and floated on the wind, When with a glancing eye thy dove Shot to thy heart the dart of love.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9514, 159)

|

In the consistent rhyme and meter that Carmelite poetry demanded, here Charles Neale faithfully represents San Juan’s theme and lexicon and at the same time culminates this passage of the poem with the most famous of Teresian images: the heart pierced by the arrow of divine love. Consistently faithful to the spirit of Carmelite poetry, in the moments in which Neale was thematically “unfaithful” to one of reformed Carmel’s founders, it was often only to be faithful to the other, as a loyal logistical, spiritual and now literary servant of the Carmelite Order.

Conclusions

On May 9, 1805, a group of five priests – four who had taken their Jesuit vows prior to the suppression of the Society in 1773 and one who had not – met at Saint Thomas Manor near the convent of Port Tobacco to decide whether to aggregate themselves to a small contingent of Jesuits who had been protected by Catherine the Great since Pope Clement XIV issued his Dominus ad Redemptor brief. The vote was affirmative, and a few months later the four priests who had taken Jesuit vows decades before renewed those vows, and the one who had not – Father Charles Neale – pronounced his vows on August 18, 1805, becoming a Jesuit after a wait of thirty-four years.(24)

With the initial aim of his life finally realized, one might have expected that Neale would set his sights on objectives and opportunities outside the small world of the convent of Port Tobacco. And indeed Neale was offered and accepted the positions of Jesuit Vice-Superior for Saint Mary’s and Charles Counties and Superior of the nearby Saint Thomas Jesuit Mission Center. But these were responsibilities that he could fulfill without leaving Port Tobacco, and when the Superior of the Maryland Jesuits chose Neale to take the important post of Master of Novices, a position that would have required him to move a significant distance away from Port Tobacco, he declined.(25) For Neale, a man who had spent nearly half of his life in the company of the Carmelites, a move that would take him away from them was unthinkable. As Sister Constance Fitzgerald writes, “It remains difficult even today to analyze Neale’s lifelong ministry to the nuns or the motivation that prompted it. Not even his superiors could persuade him to leave Mount Carmel to fill the leadership roles assigned to him when the Society was reestablished and he made his first vows as a Jesuit [...] Neither could these superiors persuade the nuns to let him go.”(26)

Indeed, even after officially becoming a Jesuit, Neale remained confessor and companion to the Carmelites of Port Tobacco and served in that capacity to the end of his life. When he passed away in 1823, he had spent more of his life serving the Carmelites than doing anything else, and even when given the chance to more fully realize his original vocation, he chose to remain among the members of the spiritual family that had provided him a home for so long.

It is clear, then, that while Neale never relinquished his ambition of becoming a Jesuit he also felt that he belonged with the Carmelites and, perhaps in some way, saw himself as one of them. His translation of the Cántico espiritual may in fact be an indication of this. It would not be entirely surprising if Charles Neale, as a person who dedicated most of his life to the service of Carmel in what were often difficult circumstances, had somehow identified with the co-founder of the reformed Carmelite Order while immersing himself in the translation of the Cántico, seeing in himself a bit of the spirit of San Juan de la Cruz. This is of course speculation, but a document found among the manuscripts that contain Neale’s aforementioned poem to Sister Clare Joseph lends some credibility to the idea: it is another poem in honor of Clare Joseph’s 1797 jubilee, addressed “From Mount Carmel in Heaven, to the Reverend Mother Clare Joseph of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, Prioress of the Teresian Nuns in Maryland”. The poem reads as follows:

Once of Great Carmel in the East,

But now of Carmel in the sky, New Carmel rising in the West I view with a propitious eye, And haste to send by safe express These verses, if they verses be, To Carmel’s worth shepherdess Verses to keep her jubilee When e’er you seek, in these you’ll find, The beauty of the Spouse you love, They’ll banish anguish from the mind, To health restore the lovesick Dove. They’ll set your heart and soul on fire Freed from all earthly cares and strife, You’ll then have only one desire: To sweetly languish into life.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9512, 436)

|

The poem is signed: “From Your Loving Father, John of the Cross.” In this homage to Clare Joseph, the “worthy shepherdess” who along with Charles Neale had established the convent in America, the “New Carmel rising in the West,” the author adopts the persona of San Juan and “speaks” with his voice. And while the poem is unattributed, given its theme and the fact that it is found among other manuscript poems composed by Neale, it is difficult to imagine a more likely candidate for its authorship than Neale himself. While surely not equating himself to San Juan in terms spiritual or literary, Neale may well have enjoyed the idea of emulating the 16th-century Spanish poet and saint, either as his translator or by “borrowing” his voice to sing the praises of another member of his adopted spiritual family.

Further, Neale may have seen certain parallels between San Juan’s circumstances and his own. Without the crisis that engulfed and nearly extinguished his own order, the Society of Jesus, Neale might never have entered into the intimate relationship he enjoyed with Carmel for so long, and as such he might never have become the translator of a poem that was itself born of a crisis almost exactly two centuries earlier, the fracture at the heart of the Carmelite Order that resulted in the creation of the branch of Carmel from which the convents of Antwerp and Port Tobacco grew. Neale may have seen himself, in some small way, as carrying on and perpetuating the work of San Juan who, like him, loyally dedicated his life to the service of Carmel and expressed his devotion to the Order through his works both spiritual and literary.

Future investigations may well uncover earlier English renditions of the Cántico espiritual, but for now it seems that Charles Neale’s translation presented here should be considered the first, coming as it does at least forty years before David Lewis’s 1864 translation and predating by an even longer period the first rhymed and metered translations of San Juan’s poetry that attempted to be faithful not only to the content but also to the form and spirit of the original.(27) This distinction being established, Neale’s engagement with San Juan and his poetry may have further historical significance. The fact that Neale’s version of the Cántico is undated creates uncertainty as to whether he composed the translation during the ten years he spent with the Carmelites in Antwerp or at some point in the thirty-four years he spent in their company in Port Tobacco. It is clear, though, that the above-cited 1797 poem in which the author adopts the voice of San Juan belongs to the latter of these two periods, and if the translation of the Cántico was also composed during Neale’s time in Port Tobacco, it would have another important distinction: while interest in and engagement with San Juan’s texts and his spirituality is well documented in 17th-, 18th- and 19th-century Europe, such interest and engagement outside of Europe is virtually unknown prior to the 20th and 21st centuries. As such, Charles Neale’s immersion in San Juan’s poetry and his possible personal identification with the co-founder of reformed Carmel may be a very early, if not the earliest, indication of the impact of San Juan and his writings outside of Europe.

In this sense Charles Neale, at once the victim and the beneficiary of the circumstances that altered the prescribed path of his life, is for now the author of the first English version of the Carmelite poetic masterpiece, likely among the first enthusiasts of San Juan and his writings in America, and surely among the most faithful translators of the Cántico espiritual.

A Spiritual Canticle between the Soul and her Spouse Jesus Christ

Composed by Rev. C. Neale (28)

1 The Soul Where has my fair one hid his face, Regardless of my piteous case? He gave the wound, then from my bed Swift as the hunted stag He fled. I sallied forth, but all in vain. Nor speed, nor cries could Him detain.

2

O! ye, who scan yon mountains high, That hides its summit in the sky, O shepherds such you seem to be, If ye my love perchance should see, O tell Him that his wounded Dove, Grows sick and faints and dies with love.

3

In search of Him, for whom I sigh, I’ll pass those floods and mountains high No blooming flower my steps shall stay, No savage beast my soul dismay, Strong forts and frontiers I defy. I’ll find my dear-one or I’ll die.

4

Ye forests planted by His hand, Ye woods that shade the fertile land, Ye tufted grove, & pleasant bowers, Ye verdant meadows decked with flowers Say tell me have you seen my Dear? O has my beauteous Spouse been here?

5

The Forest, etc. We’ve seen, O chosen Soul of Grace, We’ve seen thy fair one’s beauteous face: On us a thousand charms He shed, For as He pass’d, he turn’d His head, Where lo, these new creations rise, And steal their beauties from His eyes.

6

The Soul Who can alas! assuage my grief? Ah! None but He can give relief. Then come my joy, my sole delight, And with Thy Presence bless my sight. In thee I see, I taste, I smell, What messengers can never tell.

7

For every one that speaks to me, Relates a thousand claims of thee But whilst those charms their tongues display And fain a some-thing else would say, Transpierc’d a new, I know not why, In tort’ring extasy I die.

8

How canst thou Soul endure this strife? Why liv’st thou where there is no life? With softest touches, sweetest sighs, With sparkling, love infusing eyes, Thy Spouse has stol’n thy heart away, And canst thou be content to stay.

9

O! To my bleeding Heart apply A remedy and let me die: ‘Tis strange, ‘tis hard O! ‘tis unkind To leave me desolate behind: Why not in triumph bear away Thy wounded, fainting, dying prey?

10

O! sooth my anguish let me live, The life that Thou alone canst give! O now my love without disguise, Bless with thy beauteous light my eyes, Awake to thee their joy, their pride, And shut to ev’ry thing beside.

11

E’en should thy lovely aspect kill, This once O! gratify my will. For love, so true, so strong, so pure, As mine; there is no other cure. Naught but thy Presence can control The anguish of my troubled soul.

12

O! Sacred fountain crystal stream, Now show me in thy silver gleam, A sudden flash of heavnl’y light A vision of those eyes so bright, Of which I’ve drawn with care & art A faint resemblance in my heart.

13

The Spouse O turn, my love, thine eyes away, My soul takes flight & quits this clay. Return my dear, my beauteous Dive, For wounded by thy sighs of love, The stag sucks in from yonder height The cooling zephyrs of thy flight.

14

The Soul In thee, my Fair One, I decry [?] With foreign isles & mountains high, Sweet lonely vales & shady woods, Soft flowing streams & roaring floods, While balmy zephyrs fill my sails, With aromatic am’rous gales.

15

As beauteous as the dawn of day, The peaceful night glides swift away Harmonious solitude I find, And silent music charms the mind While kingly suppers cheer the Dove, And drown her in a sea of love.

16

A beauteous purple gleam is shed On this our peaceful fragrant bed, Thick strew’d with flowers fenc’d around, By lions in their caves profound, Besides, what charms the dazzl’d sight, A thousand shields of golden light.

17

Touch with a spark of love divine, Or grant a taste of spicy wine Extracted from the balm of love, A dropping from the Heavn’s above. And lo, the youthful virgin crew, With speed thy fragrant steps pursue.

18

Within thy inmost-vaults’ retreat, Of my beloved, who’s wondrous sweet, I drank my fill: But when again, He led me to the verdant plain, My tow’ring mind would not descend, To dwell with flocks on things that end.

19

‘Twas there he took me to his bed, And on me sweetest science shed, ‘Twas there that I with hand & heart, Gave all I had or could impart, And bound myself by solemn vows, To ever be His faithful Spouse.

20

To serve Him now is all my pride, No longer flocks my care divide, On contemplative heavn’ly wings, I’ll soar above all earthly things And love shall be my sole employ, My only exercise & joy.

21

To know why on the busy green, No longer I am heard nor seen, Should curious shepherds you accost, Say, tell them I myself have lost. Charm’d by a graceful, stranger swain, O happy loss that proves such gain.

22

Of emeralds & of flowers in May, Fresh gather’d at the dawn of day, We’ll fair [?] crowns that never will fade, But ever flourish in thy shade And then I’ll bind those crowns so fair, Together with a single hair.

23

With that same hair, whose magic power The captive made in yonder bower, As graceful on my neck behind, It play’d & floated on the wind, When with a glancing eye thy dove, Shot to thy heart the dart of love.

24

That amr’ous look, those eyes divine, First left their beauties stamp’d on mine, And therefore didst thou love my face, Adorn’d by thee with ev’ry grace; And therefore didst thou give me right, T’adore thee & t’enjoy thy sight.

25

Condemn me not because my face, At first was brown & void of grace, For ever since those eyes divine, Left beauty’s portrait mark’d on mine, My face from brown is changed to white, And must be pleasing to thy sight.

26

Permit me not to be annoyed: But let those foxes be destroyed: Now as our vineyard is in flower, Of roses let us form a bower, And on that pleasant hillock’s plain, Let there be seen nor flock nor swain.

27

Fierce Boreas with thy blasting mouth, Approach me not, come lovely south, On balmy wings, in am’rous breeze, Pass through my garden, flowers & trees, That midst thy fragrancy divine With me my royal spouse may dine.

28

The Spouse Within the garden of her love, Amidst the fragrant myrtle grove, Now seated by her lover’s side, Upon his arm, the beauteous Bride, With neck inclined, in sweetest doze, Enjoys the wished for bless’d repose.

29

‘Twas underneath that apple tree, That I engaged my word to thee, There by one look, I changed thy face, From brown to white in that same place, Where by the serpent’s wiles o’erpowered, Thy hapless mother was deflowered.

30

Ye birds light as the wind that blows, Ye lions, stags & bounding roes, Ye mountains, valleys, rivers clear, Ye waters, scorching heats & air, Attendants on the wakeful nights Ye humbling horrors, dreads & frights,

31

By the sweet lyre’s harmonious sound, By sirens’ notes that echo sound, I now conjure you to assuage, Your burning anger, fury, rage; Touch not the wall, nor dare to rouse, From sweet repose, my darling spouse.

32

The Soul Ye beauteous nymphs of Juda hear, And listen with attentive ear: While on my rose trees in their bloom, The amber sheds its rich perfume, Presume not to approach my gate, But peaceful in the suburbs wait.

33

Behold those mountains high my Dear, Admire my virgin train so fair; Then hide thyself & let it be, A secret ‘twixt my spouse and me; For now made happy by thy smiles I’ll fearless pass through unknown isles.

34

The Spouse With branch of olive evergreen, Once more the milk-white dove is seen Within the ark, and all her fear, Her toils, her troubles disappear; For, where a river forms a cove, She now enjoys her long lost love.

35

In solitude she built her nest, In solitude she sought for rest, And in the lonely bless’d retreat, The lover deign’d his love to meet, Well pleased in solitude to find, A bride so beauteous, chaste & kind.

36

The Soul In the bright mirror of thine eyes, We’ll view ourselves & then we’ll rise. And to the hills & mountains go, From whence the crystal waters flow; There midst the thickest, gloomy grove Conceal’d from mortal view we’ll rove.

37

Unto those rocky caves so high, So far remov’d from mortal eye, Let’s haste, my love & in those cells, Where heav’n-born contemplation dwells. We’ll on the choicest dainties dine, And drink the sweet pomegranate wine.

38

Within those grotts, in sweet repose, My spouse his secrets will disclose; His hidden treasures he’ll display, And, what he gave the other day, He’ll grant anew, & kindly show, All that I hope or wish to know.

39

And if my fairest fair one please, I’ll then enjoy the zephyr’s breeze, The ornamental woods, the night, Clad in her spangled robe of sight, With Philomena’s warbling strain, And fire consuming without pain.

40

No mortal eye can see me here; Aminadab dare not appear; The foes, that were encamp’d around, Lie buried in a sleep profound; And now the horsemen side by side, In peace down to the waters ride.

(Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9514, 155-168)

|

NOTES

(1) An account of Charles Neale’s life and work is given in “Father Charles Neale S. J. and the Jesuit Restoration in America,” Laurence J. Kelly, S. J., The Woodstock Letters, LXXI, 3, October 1942, pp. 255-290.

(2) Ward, Bernard, "College of Saint Omer," The Catholic Encyclopedia, 13, New York, Robert Appleton Company, 1912.

(3) Kelly, 260.

(4) Ibid., 261.

(5) Currier, 54.

(6) Fitzgerald, 21.

(7) For an account of the voyage made by Neale and the Carmelites from Europe to America, see Sister Clare Joseph’s travel journal written during the trip, given in Fitzgerald, 54-81.

(8) In her letters, Teresa insists on the importance of the practice of composing and sharing verses in the convents she had founded: in a letter to María de San José, the prioress of the Carmelite convent of Seville, she wrote, “He mirado cómo no me envían nengun villancico, que a usadas no havrá pocos a la eleción” (Obras completas, 1257), and in another letter to María de San José, Teresa wrote, “De cómo le va en lo spiritual no me deje de escribir... y las poesías también vengan. Mucho me huelgo procure que se alegren las hermanas, que lo han menester” (Obras completas, 1352). For an explanation of the function of poetry in the life of Teresian Carmelite convents, see the Libro de romances y coplas del Carmelo de Valladolid (c. 1590-1609), eds. Victor García de la Concha and Ana María Álvarez Pellitero, 2 vols (Salamanca, Consejo General de Castilla y León, 1982), and Ana María Álvarez Pellitero, "Cancionero del Carmelo de Medina del Campo", in Congreso Internacional Teresiano, 4-7 octubre, 1982, eds. Teófanes Egido Martínez, Víctor García de la Concha, and Olegario González de Cardedal, 2 vols. (Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca, 1983), II, 525-43.

(9) Nicolás, in John of the Cross (1996), 4.

(10) Certeau, 129.

(11) This manuscript translation, like the poems by Neale and Sister Clare Joseph cited earlier, is housed in the archives of the Carmelite convent of Baltimore, Maryland, and in digital copies in the Archives of the State of Maryland.

(12) See García de la Concha, 341-342.

(13) San Juan de la Cruz, Poesía, ed. Domingo Ynduráin, 249.

(14) Lewis, 4.

(15) San Juan de la Cruz, Poesía, 249.

(16) While Neale’s translation of the poem is indeed quite faithful in terms of lexicon and theme, one difference in his treatment of the opening stanza should be recognized, namely the mode of address that Neale shifts from San Juan’s familiar second person (tú) to the third person (Him).

(17) San Juan de la Cruz, Poesía, 250.

(18) Teresa, Obras completas, 108

(19) Ibid., 158.

(20) Ibid., 654.

(21) San Juan de la Cruz, Poesía, 251.

(22) Teresa, Obras completas, 654.

(23) San Juan de la Cruz, Poesía, 256.

(24) Kelly, 279.

(25) Ibid., 284.

(26) Fitzgerald, 29.

(27) Philip Boyce has given a brief but useful inventory of some of the modern English translations of San Juan’s poetry that have been published. Besides E. Allison Peers’ 1946 translation of the Cántico, which Peers gave in two versions, one rhyming and metered and one not, Boyce points out in particular the 1920 rhyming and metered translation of the Noche oscura by Arthur Symonds and also the translation by Lynda Nicholson of the Cántico that appears in Gerald Brenan’s Saint John of the Cross: His Life and Poetry, in which Nicholson employs assonance, but not rhyme or consistent meter, to convey some of the musicality of the original. See The Influence of Saint John of the Cross in Britain and Ireland, 108-109.

(28) Interestingly, there is no indication in the manuscript of Neale’s translation that it is, in fact, a translation. As the title given here indicates, the poem appears simply as “ A Spiritual Canticle…Composed by Rev. C. Neale”. No mention is made of San Juan de la Cruz, and no indication is given as to the original source of the text.

A note regarding the version of the Cántico translated by Neale is also in order: today there are two versions of the Cántico which are generally recognized, the thirty-nine-stanza “Cántico A” and the forty-stanza “Cántico B” which, apart from containing different numbers of stanzas, also differ in the overall sequence of the stanzas. Interestingly, Neale’s translation of the poem does not follow the sequence and content of either of these two versions. It does, however, correspond closely to a version of the poem that appears in a 1694 Spanish edition of San Juan’s Obras, which consists of all forty stanzas of the Cántico B but in a sequence more closely resembling that of Cántico A (see Works Cited, Paredes). As such, both the 1694 Spanish edition and Neale’s translation produce a hybrid of “A” and “B”. Whether or not Neale based his translation on the 1694 edition is not known, but this seems likely given the close correspondence between the two.

Works Cited

Print Sources

ÁLVAREZ PELLITERO, Ana María, “Cancionero del Carmelo de Medina del Campo”, Actas del Congreso Internacional Teresiano, 4–7 octubre, 1982, ed. Teófanes Egido Martínez, Víctor García de la Concha and Olegario González de Cardedal, t. II, Salamanca, Universidad de Salamanca, 1983, pp. 525–543.

BOYCE, Philip, “The Influence of Saint John of the Cross in Britain and Ireland,” in Teresianum, 42, 1991/1, 97-121.

BRENAN, Gerald, Saint John of the Cross: His Life and Poetry, Cambridge (England), Ambridge University Press, 1973.

CERTEAU, Michel de, The Mystic Fable, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1992.

CURRIER, Charles Warren, Carmel in America: A Centennial History of the Discalced Carmelites in the United States, Baltimore, John Murphy, 1890.

DICKINSON, Clare J., and Constance FITZGERALD, The Carmelite Adventure: Clare Joseph Dickinson’s Journal of A Trip to America and Other Documents, Baltimore, Carmelite Sisters, 1990.

GARCÍA DE LA CONCHA, Víctor, and Ana María ÁLVAREZ PELLITERO, Libro de romances y coplas del Carmelo de Valladolid (c.1590–1609), 2 vols., Salamanca, Consejo General de Castilla y León, 1982.

JOHN OF THE CROSS, St. John of the Cross: Alchemist of the Soul, trans. Antonio T. de Nicolás, York Beach (ME), S. Weiser, 1996.

—— The Complete Works of Saint John of the Cross, Doctor of the Church, ed. E. A. Peers and Silverio de Santa Teresa, Westminster (MD), Newman Bookshop, 1946.

—— and David LEWIS, The Complete Works of Saint John of the Cross of the Order of Our Lady of Mount Carmel, London, Longmans, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green, 1864.

JUAN DE LA CRUZ, Poesía, ed. Doming Ynduráin, Madrid, Cátedra, 1983.

—— Obras del Beato Padre Fray Juan de la Cruz, Madrid, Julian de Paredes y a su costa, 1694.

KELLY, Laurence J, “Father Charles Neale S. J. and the Jesuit Restoration in America,” in The Woodstock Letters, LXXI, 3 (October 1942), 255-290.

SYMONDS, Arthur, “The Poetry of Santa Teresa and San Juan de la Cruz,” in The Contemporary Review, 75, 1899, 542-541.

TERESA OF ÁVILA, Obras completas, ed. Efrén de la Madre de Dios and Otger Steggink, Madrid, Biblioteca de autores cristianos, 2003.

WARD, Bernard, "College of Saint Omer," The Catholic Encyclopedia, 13, New York, Robert Appleton Company, 1912.

Manuscript Sources (Housed in State Archives of Maryland, Annapolis)

Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9513

Archives of the Carmelite Convent of Baltimore, SCM 9514

A Journal of Translation Histoy

No comments:

Post a Comment