|

| Clive James |

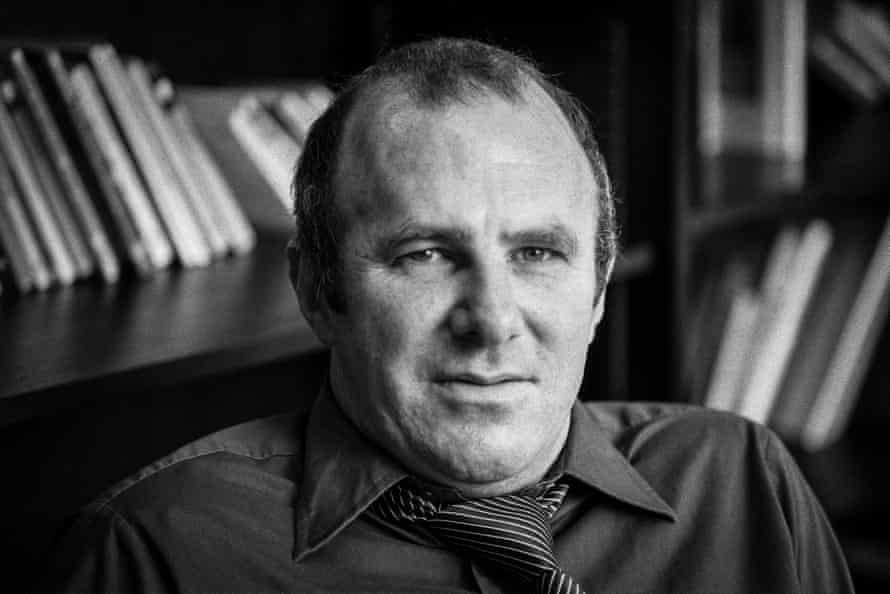

Clive James obituary

Writer, poet and critic who found fame as a presenter of TV shows such as Saturday Night Clive

Stuart Jeffries

Wed 27 November 2019

The writer and broadcaster Clive James, who has died aged 80, once wrote a poem about visiting his father’s grave at the Sai Wan war cemetery in Hong Kong. His father, Albert, who had survived a PoW camp and then forced labour in Japan, died when the plane bringing him home crashed in Taiwan, and James later described this as the “defining event” in his life. The poem, My Father Before Me, ends:

Back at the gate, I turn to face the hill,

Your headstone lost again among the rest.

I have no time to waste, much less to kill.

My life is yours; my curse, to be so blessed.

James, who was six when Albert died, spent much of his subsequent life as a poet, essayist and broadcaster producing articles and song lyrics, many poetry collections and volumes of critical essays, four novels and five books of memoirs, as well as hosting umpteen television shows. That fever of busyness was to compensate not only for his father’s death, but for how his mother’s life fell apart on being widowed. “I am trying to lead the life they might have had,” he said in 2009. “It’s a chance to pay them back for my life. I don’t like luck; I’ve had a lot of it.”

James was born in Kogarah, a suburb of Sydney, Australia. His mother, Minora (nee Darke), named her only child Vivian, after the male star of the 1938 Australian Davis cup team. It could have been worse. There was, James noted in Unreliable Memoirs (1979), a famous Australian boy whose father named him after his campaigns across the Western Desert: he was called William Bardia Escarpment Qattara Depression Mersa Matruh El Alamein Benghazi Tripoli Harris.

Vivian James was spared further feminisation when Gone With the Wind was released. “After Vivien Leigh played Scarlett O’Hara, the name became irrevocably a girl’s name no matter how you spelled it,” he wrote, so his mother let him become Clive after a character in a Tyrone Power movie.

A bright child with an IQ of 140, James went to Sydney technical high school, and studied psychology at the University of Sydney. While there he was not only literary editor on the student paper, Honi Soit, and director of the student revue, but also took part in the Sydney Push, a libertarian, intellectual subculture that flourished in pub back rooms and whose associates included Germaine Greer and Robert Hughes. After graduating, he served for a year as an assistant editor of the magazine page at the Sydney Morning Herald before sailing to London at the age of 22. There, he shared a flat with the Australian film director Bruce Beresford, became friendly with Barry Humphries and spent three years paying the rent as a sheet-metal worker, library assistant, photo archivist and market researcher.

He then studied for a further degree in English at Pembroke College, Cambridge, but did not read the required books. Instead, he became president of Footlights and established himself as a critic. “Reading off the course was in my nature. My style was to read everything except what mattered.” He nonetheless surprised himself by getting a 2:1, and began a PhD on Shelley.

“Television brought James the riches and fame he craved,” wrote one hostile critic. “But as far as his ambitions to have been an artist of merit are concerned, he squandered his talent, which is tragic.” Unfair: there was never a sense in which he sought riches, nor was his case tragic. There is an image of him going home after a show by tube, reading Tacitus in the original, which suggests that, rather than tragic, James was interestingly conflicted – or perhaps just culturally omnivorous. In any case, the man who made a TV series analysing the concept of fame knew what it took for a bald man with eyes so deep-socketed they were scarcely visible to have an enduring on-screen career. “The smartest move I ever made in show business was to start off looking like the kind of wreck I would end up as.”

Some made great claims for his literary talents. Writing under the headline As Good as Heaney in 2009, Julian Gough in Prospect magazine championed two volumes of James’s collected verse. But how could one take seriously a TV critic who wrote satirical verse epics such as The Fate of Felicity Fark in the Land of the Media: A Moral Poem (1975) or Peregrine Prykke’s Pilgrimage Through the London Literary World (1976), still less compare them to the Nobel laureate’s?

Gough argued: “James is an absolute master of surface, and the great critic of surfaces, not because he is superficial but because he believes that the distortions on the surface tell you what’s underneath. Style is character. His simplicity isn’t simple and his clarity has depth. With the essays and the poems – which I think you have to consider as one great project – he’s built an immense, protective barrier reef around western civilisation.”

Perhaps. But questions remained. Would Endurance, the Japanese game show in which contestants were buried up to the neck, bitten by ants and licked by lizards and upon which James spent so much tittering airtime, be inside that protective barrier reef? And, more importantly, was James a highbrow hypocritically conniving at what he affected to disdain? Probably not. He wrote in the introduction to Glued to the Box: “Anyone afraid of what he thinks television does to the world is probably just afraid of the world.”

“Television brought James the riches and fame he craved,” wrote one hostile critic. “But as far as his ambitions to have been an artist of merit are concerned, he squandered his talent, which is tragic.” Unfair: there was never a sense in which he sought riches, nor was his case tragic. There is an image of him going home after a show by tube, reading Tacitus in the original, which suggests that, rather than tragic, James was interestingly conflicted – or perhaps just culturally omnivorous. In any case, the man who made a TV series analysing the concept of fame knew what it took for a bald man with eyes so deep-socketed they were scarcely visible to have an enduring on-screen career. “The smartest move I ever made in show business was to start off looking like the kind of wreck I would end up as.”

Some made great claims for his literary talents. Writing under the headline As Good as Heaney in 2009, Julian Gough in Prospect magazine championed two volumes of James’s collected verse. But how could one take seriously a TV critic who wrote satirical verse epics such as The Fate of Felicity Fark in the Land of the Media: A Moral Poem (1975) or Peregrine Prykke’s Pilgrimage Through the London Literary World (1976), still less compare them to the Nobel laureate’s?

Gough argued: “James is an absolute master of surface, and the great critic of surfaces, not because he is superficial but because he believes that the distortions on the surface tell you what’s underneath. Style is character. His simplicity isn’t simple and his clarity has depth. With the essays and the poems – which I think you have to consider as one great project – he’s built an immense, protective barrier reef around western civilisation.”

Perhaps. But questions remained. Would Endurance, the Japanese game show in which contestants were buried up to the neck, bitten by ants and licked by lizards and upon which James spent so much tittering airtime, be inside that protective barrier reef? And, more importantly, was James a highbrow hypocritically conniving at what he affected to disdain? Probably not. He wrote in the introduction to Glued to the Box: “Anyone afraid of what he thinks television does to the world is probably just afraid of the world.”

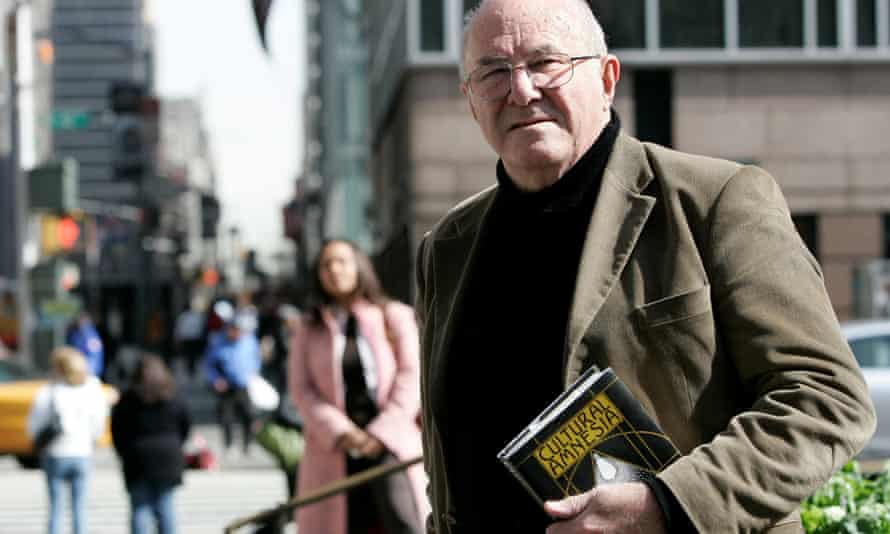

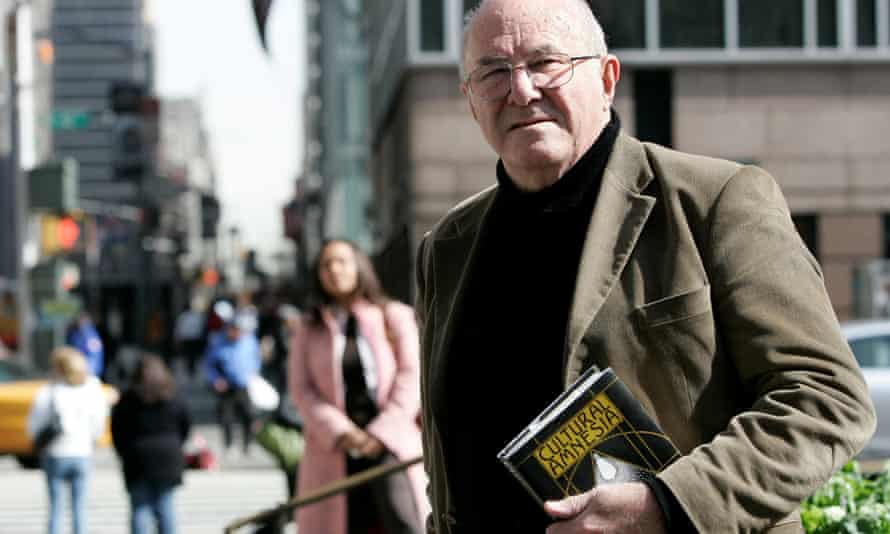

Clive James with his book Cultural Amnesia, 2007, a collection of biographical essays. Photograph: Shannon StapletonJames claimed to have an “ungovernable ego” but was quite capable of uxoriousness. He was married to Prue Shaw, a Cambridge scholar, with whom he had two daughters: Claerwen and Lucinda. James protected all three from media intrusion, though he gave an insight into his admiration for his wife when he produced her book on Dante for an interviewer: “That’s the real McCoy. That will always be there. The kind of stuff I do is more conjectural. I am still trying to impress her.” He once said: “I think marriage civilised me. It may sound sexist, but it is one of the roles of women to civilise men.”

He betrayed his wife by having an eight-year affair with a former model, Leanne Edelsten. When Shaw discovered the affair, in 2012, she threw him out of their Cambridge home, and he moved to a London flat. “I am a reprehensible character,” he told one interviewer. “I deserve everything that has happened to me.”

His mainstream TV career ended with the 20th century, but James was not done. He set up clivejames.com, billing it “the world’s first personal multimedia website of its type”. He did an internet show, Talking in the Library, including conversations with Ian McEwan, Julian Barnes and Terry Gilliam. He reviewed widely for the New York Review of Books, the London Review of Books, the TLS, the New Yorker, the Australian Book Review and the Guardian, and wrote Cultural Amnesia (2007), a collection of biographical essays on mainly 20th century writers, artists and politicians. He made 60 broadcasts for the BBC Radio 4 series A Point of View (2007-09) and in 2008 performed two comedy shows at the Edinburgh festival.

In his later years he worked harder than ever. He told one interviewer: “You get into what my friend Bruce Beresford calls the Departure Lounge, and two things happen: suddenly time really matters, you can hear the clock, and also you have all these freedoms, because you’ve got more of life to reflect on.”In January 2010, he was diagnosed with terminal leukaemia. One of the greatest annoyances his cancer and its treatment caused him was that he was not allowed to fly – thus stopping him visiting his beloved homeland. But he kept writing, including a weekly TV review for the Daily Telegraph for three years until 2014.

An Indian summer of writing was just beginning, long after the valedictory interviews were done. He wrote a translation of Dante’s The Divine Comedy (2013), a collection of essays, Poetry Notebook: 2006-2014 (2014) and an analysis of the radical change in TV viewing habits, Play All: A Bingewatcher’s Notebook (2016).

In 2015, he published a volume of poetry, Sentenced to Life, that expressed the loss and guilt he felt for his infidelity and betrayal of his wife and daughters. This book and the Dante translation became bestsellers, and both were dedicated to Prue, with whom he had reached a reconciliation. In the poem Landfall he wrote, “I am restored by my decline / And by the harsh awakening it brings”. The poem Event Horizon ends with the following reflection:

What is it worth, then, this insane last phase

When everything about you goes downhill?

This much: you get to see the cosmos blaze

And feel its grandeur, even against your will,

As it reminds you, just by being there,

That it is here we live, or else nowhere.

That year he published a further collection of literary essays, Latest Readings (dedicated to “my doctors and nurses at Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge”) and found a new berth as a columnist, with Reports of My Death, in the Guardian’s Weekend magazine, which ran until 2017. He also released an album with his longtime songwriting partner Pete Atkin, The Colours of the Night, and went on to produce another poetry collection, Injury Time (2017) as well as the epic poem The River in the Sky (2018).

He was appointed CBE in 2012 and AO in 2013. In 2008 he was awarded a George Orwell special prize for writing and broadcasting, and in 2015 he received a special award from Bafta for his contribution to television.

He is survived by his wife and daughters.