New mysteries surface over Lorca’s final resting place

Letters show poet’s friend believed his remains were moved by his family or Franco regime

Seville 20 AGO 2015 - 03:08 COT

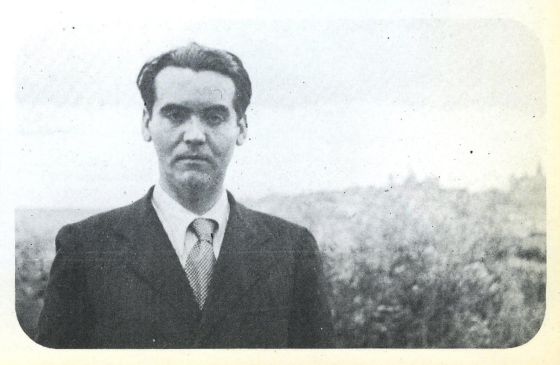

Some deaths, such as that of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca, transcend the life of the person.

As the 79th anniversary of the Spanish poet’s execution is commemorated this week, new light has been shed on the decades-old mystery surrounding his final resting place.

For years, historians have been digging in search of his body near the site in Granada province where witnesses claimed that he was shot dead by Nationalist supporters in 1936.

When Penón asked about her source, Llanos only told him it was “a high official”

But a new book by author Marta Osorio lends support to the idea that the poet may have been secretly removed long ago from its original burial place by either his family or the Franco regime.

Osorio has compiled letters and other correspondence between Lorca’s close friend Emilia Llanos (1886-1967) and Agustín Penón (1920-1976), one of the first researchers to conduct an exhaustive study into the poet’s final days.

The book, entitled El enigma de una muerte: Crónica comentada de la correspondencia entre Agustín Penón y Emilia Llanos (The mystery of a death: An annotated chronicle of the correspondence between Agustín Penón and Emilia Llanos) and published by Comares, is a follow-up to Osorio’s acclaimed Miedo, olvido y fantasía: crónica de la investigación de Agustín Penón sobre Federico García Lorca (Fear, obscurity and fantasy: A chronicle of Agustin Penón’s research on Federico García Lorca).

“NOTHING HAS BEEN DONE”

“Despite everything, Federico will live on forever – for a much longer time after all of us are dead – and if the real facts are not clarified then they will be replaced by fantasy,” wrote researcher Agustín Penón in 1955. “And passionate fantasy could become merciless.”

In her new book, Marta Osorio believes that Penón “anticipated what was going to happen from the first day” he began his research into Lorca’s death,

The author still cannot believe that “there are so few proven facts” 79 years after the poet’s death, which “leaves many questions open.”

“Not one thing has been done and no one knows a thing,” she says.

Even if Lorca’s remains are never found, Osorio believes that the authorities should embark on a search for the bodies of other Civil War victims in the area.

In her book, she describes a young Jewish-German girl who fled the Nazis in her country and was later executed by Spanish Nationalists because she had been a friend of a Socialist architect.

Osorio knows all too well the wounds that the Francoist repression left. From her home in Granada’s El Realejo neighborhood, she can see houses that once belonged to councilors, intellectuals and teachers who were executed during the Franco regime.

“If you dig deep enough, you will discover a lot of things,” says journalist Isabel Reverte, author of the documentary La maleta de Penón.Penón, a native of Barcelona who held US citizenship, arrived in Granada in 1955 with his friend, the American radio actor and producer William Layton.Carrying his beloved first edition of Lorca’s Romancero gitano, Penón knew at the time that he was in a city where mentioning “Federico’s name was prohibited,” Osorio says.

With no wish to “stir up passions” – as he later said – he began to investigate and establish the “chronology of the crime,” which took him more than one-and-a-half years to research and is now considered one of the most important investigations into the poet’s death.

After interviewing witnesses and closely inspecting the road between the towns of Alfacar and Viznar and the ditch where the Nationalists executed hundreds of people, Peñón came up with a short list of sites where Lorca’s remains could be buried.

During his stay in Spain, he met Emilia Llanos, one of Lorca’s closest friends with whom he maintained in written contact for the rest of his life.

But pressure from the Francisco Franco dictatorship made him fear that his research papers would be confiscated and Penón left for New York in 1956 with a suitcase full of documents, which ended up in the hands of Osorio.

Layton gave her the suitcase before he died in 1995.

Penón concluded that Lorca’s grave was located underneath an olive tree, around 10 meters from the highway and close to the large fountain in what is now García Lorca park.

Letters show that Penón tried to purchase the land after Llanos had told him it had been put up for sale in 1957. But two months later, they canceled their plans.

“We have to abandon that idea for now, it is not a good moment,” wrote Llanos.

Two months later, she explained why she had backed out: “The one who was once there is no longer there. Do you understand what I am saying? For a long time it has been well-known that he is in Madrid with his family. I was told this by someone who has knowledge.”

When Penón asked about her source, Llanos only told him it was “a high official” but never revealed the identity. Her letters are marked by her fear of reprisals by the dictatorship.“Yes, the site was near the olive trees but later they took him to another site,” Llanos said.

“The letters add uncertainty,” says Osorio, who adds that the Nationalists could have exhumed the body to prevent the area from becoming a pilgrimage site for those who supported democracy.

She also hypothesizes that, alternatively, Lorca’s family might have had something to do with the poet’s exhumation.

Recent digs in 2009 and 2014 by Andalusian regional authorities at the site near and around his execution failed to turn up any of the poet’s remains.

Osorio does not give official backing to any of these theories and refuses to get caught-up in the speculation over Lorca’s final resting place.

“Many things have been said and some have basis in truth but they only add to the confusion,” she says.

No comments:

Post a Comment