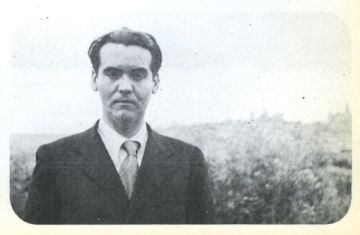

Ian Gibson: A life with Lorca

Irish-born scholar’s work on writer to be reprinted to mark 80th anniversary of his death

English version by Susana Urra

Jesús Ruiz Mantilla

25 January, 2016

Life with Federico García Lorca is a pilgrimage that involves carrying the load of injustice on your back.

It has its moments of satisfaction, says scholar Ian Gibson, but also its sorrows – such as realizing that some people in Spain still prefer ignorance over knowledge of what happened on the day a firing squad ended the writer’s life at the onset of the Spanish Civil War.

Ever since he was a young 18-year-old student in Dublin, Gibson has spent most of his time unraveling the mysteries that surround the Spanish author of Blood Wedding and Poet in New York. His complete works on the subject are to be reprinted this year, to coincide with the 80th anniversary of Lorca’s murder on August 19, 1936.

“He is the most famous missing person in the world,” says Gibson, alluding to the fact that Lorca’s body has still not been found despite several high-profile attempts.

Sitting inside a bar in Lavapiés, the Madrid neighborhood where he lives, Gibson explains how Lorca became the focal point of his career. “It could have been Baudelaire,” he admits. “But it was Federico who dazzled me.”

At age 76, he still doesn’t quite know why. “It was a very intimate, very profound thing that his poetry revealed to me. It had to do with the atavistic, with something primitive and instinctive. He was an eminently telluric poet.”

“It could have been Baudelaire. But it was Federico who dazzled me”

His first reading of El romancero gitano(translated as Gypsy Ballads) left a mark for life. Later, piqued by clues offered by Gerald Brenan in his 1950 book The Face of Spain, Gibson decided to investigate Lorca’s killing.

The result was his book The Death of Lorca, which addressed a taboo subject in 1970s Spain, then still under the yoke of Francoism.

Later came his main work, the 1998 biography Vida, pasión y muerte de Federico García Lorca, and offshoots such as 2009’s Lorca y el mundo gay and the more recent Poeta en Granada (2015).

“People think I’m obsessed,” he says, before admitting that maybe it is no wonder. “He is everything to me.”

Whether he likes it or not, Lorca is the central element that has enabled Gibson to approach other areas of research. It was Lorca who led him to Salvador Dalí, Antonio Machado and Rubén Darío, whose biographies he ended up writing as well.

Gibson also played a role in the efforts to exhume Lorca’s body after putting forward a possible location of the mass grave in which he is thought to lie, together with a schoolmaster and two bullfighter assistants. That attempt proved fruitless, as did the others.

“I have gone over the notes, the recordings. I still think he is buried very near the memorial park in Alfacar, but I have no problem with people investigating other possibilities, like the researchers Miguel Caballero, Javier Navarro and their people are doing,” he says. “All leads must be followed, no doubt. All I am interested in are the scientific results.”

But Gibson is not just attracted to the shadows surrounding the writer’s death. He is also intrigued and moved by certain episodes in his life.

“He had this sense of abandonment during his childhood years. Perhaps there was a wet nurse. His love trauma must have come from some very deep place. Like he used to say: every abandoned child is a story that got erased.”

But there was a lot of light in his life as well: there was joy, there was music, and a passionate determination to follow up on what he called his inclinations. Nobody can be left indifferent after getting to know Federico. To study Lorca is to study inner prisons and how to escape from them.

Gibson had found a soulmate. “He taught me both to detect and to wish to free myself of the puritanical environment I experienced as a child in a Protestant family surrounded by a Catholic country,” he notes.

“If I live in Lavapiés, it’s because of him, because this is where I came searching for his trail,” he adds. “I never dreamed I would end up living here.”

Ultimately, he even applied for dual citizenship. This has been a source of joy and sadness, as Gibson cannot understand why his adoptive country sometimes seems unwilling to get to the bottom of the Lorca issue.

Not that he hadn’t been forewarned “by a great observer of this country, Richard Ford,” he says about the 19th-century travel writer who wrote the influential A Handbook for Travellers in Spain.

“In one of the passages he comes up with a dazzling definition of this country,” says Gibson: “Unamalgamating Spain.”

No comments:

Post a Comment