Simon Armitage: Making poetry pay

One Indian summer evening last September, off a busy slip road not far from the Tower of London, Simon Armitage took to the stage of the world’s oldest surviving music hall and, after a short introduction from the broadcaster Melvyn Bragg, started to read. “It begins with a house, an end terrace / in this case …” The hall was full, generous with silence and later with laughter: young couples in careful retro outfits, men in suits dropping by after work, students, and older women; audience and performers held beneath a glowing tent of wobbly fairy lights that rose from the balconies to a bright apex in the roof. “But it will not stop there. Soon it is / an avenue / which cambers arrogantly past the Mechanics’ Institute …” Armitage’s reading voice is light; not exactly monotonal, but strung on a more delicate, questioning skein than his conversational voice. The poem, Zoom!, the title piece in his very first collection, in 1989, turns left at the main road, leads to a town, “city, nation, hemisphere, universe, … [is] bulleted into a neighbouring galaxy”, before finally coming to rest in the checkout queue at the local supermarket.

How did the poem come about, Bragg asked. Daydreaming, answered Armitage: “I’d been bunking off school – which was a bit of a worthless pastime in those days because it was before daytime TV.” The audience laughed. He spoke of the challenge, these days, of building thinking time into a day. “‘What have you been doing?’ ‘Thinking’” – another murmur of laughter – “It sounds like an excuse, but actually, it’s vital.” It was a deft, confident performance, an unstrained mixture of taking himself and his work seriously while making sure to puncture anything that might come across as pretension; playing with anti-intellectualism while depending on the fact that no one would be here if they were not intellectually engaged. Did he plan his poems? “I know other poets who work on poems as exploration, but I’ve usually got a destination in mind. I knew in that poem I wanted to end up in Sainsbury’s supermarket” – a slight pause, as the audience guffawed – “it was just a question of getting back from the outer periphery of the universe.”

The laughter was prolonged, and it came from a core of true respect: Armitage is not only a gifted performer, he is also spoken of as the next poet laureate and the most popular British poet since Philip Larkin; this month he threw his hat into the ring as a candidate to become Oxford professor of poetry (sole requirement: “that candidates be of sufficient distinction to be able to fulfil the duties of the post”). Most of all, from the beginning of his career, Armitage has been a leading example of how a poet might impose him or herself on a culture that is increasingly disinclined to reward poetry – and earn a living from doing so.

For while poetry might sometimes seem to be everywhere – on underground trains, buildings, Facebook, at spoken-word events; as a piece in Newsweek noted last year, “everything from Chester Zoo to the Great North Run” seems to have its poet-in-residence – this doesn’t tend to translate into actual financial viability. Most first-time collections sell a few hundred copies if their authors are lucky. For most poets, self-promotion and performance these days are imperative in order to gain any readership at all, and Armitage – arguably the consummate poet-professional – has come round to making a virtue of that, even a kind of manifesto: “I used to have a purist view of poetry, that the page was all there was,” he said at the Oxford Union in May. “I don’t think that any more. A poet is the entire package. Poetry goes back to the campfire, the theatre, and the temple.”

So, in one typical two-week period last September, Armitage did the following, and more: worked on a dramatised version of the Raft of the Medusa for Radio 4 (broadcast in April and now in development at the National Theatre); worked on a translation of the medieval poem Pearl (now finished); went to an exhibition by someone who is painting his portrait; met musicians with whom he may collaborate on a spoken-word project; appeared on Radio 3; led a poetry writing workshop at the Wakefield literary festival; had meetings at the Liverpool Everyman theatre to discuss a dramatisation of The Odyssey (it will transfer to Shakespeare’s Globe in London in November); did interviews about a film he had made for the Culture Show; met his new students (he is professor of creative writing at Sheffield); wrote notes for one poem, began another, finished yet another; and did a reading, with the poet Jamie McKendrick, in Modena, Italy. Poetry has taken him to the Amazon and to Iceland, to the US and to New Zealand, on to helicopters, trawlers, trains; to prisons and to residencies at Eton, to conference halls filled with up to 2,500 GCSE students (his poems are on the syllabus). Armitage now has an agent who manages the performing side of his life; he estimates he says yes to about 50% of requests.

Over nine months, I accompanied him to some of these events, and began to see exactly how such a significant presence has to be shaped and managed – and to realise that, in this regard, Armitage has a mastery developed over decades of give and take between what has been demanded of him and what he chooses to offer. In West Yorkshire, where he grew up, I did not suggest an itinerary – he did. When we climbed to the top of Pule Hill, I knew he had been there with journalists before, also tracing the lineaments of his poems and life: “We are making a film,” he wrote in Gig, his engaging memoir of a lifelong relationship with popular music, about taking a BBC camera crew up there. “Each region has been asked to profile one of its artists. I am THE NORTH.” Production HQ for the film, he wrote, was his parents’ house; they re-enacted one of his poems, setting a tyre in freefall down the hill. His description of the process was as gentle and blokey, self-mocking and sincere as he often is in person.

But it also smuggled in a very controlled picture of how he wants to be seen. “I am THE NORTH” laughs at the reductiveness of the media – but does not deny it, in part because it is true; he is from the north and proud to be so. Indeed, being “the north” is an aspect of an artistic modus operandi that has over the years proved quite useful – as differentiation from other poets, as a grounding, authenticating narrative of class and language. During our walks, and before and after various events to which I accompanied him, Armitage almost always gave generous and direct answers to my many questions. But I was also – unintentionally, I think – given a masterclass in brand management, all the more skilful because, while not necessarily always reflective of the distance he has travelled from his roots, it does not feel fake. Nor does it obscure Armitage’s unapologetic belief in the importance of poetry, his willingness to advocate for it, and his adamantine sense of vocation.

Along the way, I met many critics who thought none of this could replace high seriousness: popularity (in a post-Pound, post-Eliot era full of prickly moralising about the virtues of being ignored) was simply assumed to be incommensurate with quality or greatness. There was an overriding sense, as Ian Gregson, a poet and author of a book-length study of Armitage put it, that “I can understand it, so it must be crap”. Back on stage in London, Bragg took the issue head on. Was Armitage aware of the criticism? “I became more and more aware as people pointed it out to me in reviews.” A general laugh. “I suppose what I’ve come to think is, it’s fine. It’s a broad church. I’ve got a lot of respect for people who write obscure avant-garde poetry, but it’s not the poetry I want to write.”

“He’s not at all simplistic,” said Gregson. “He’s actually trying – and this to me is the ideal – to take on the most difficult, complex things possible but to deal with them as accessibly as he can.” The poet Glyn Maxwell, who travelled with Armitage through Iceland, retracing the route taken by WH Auden in 1936 for their book Moon Country (1996), put the criticism down to simple envy. “It’s the cheapest way to treat someone who’s flown quite high.”

So high, in fact, that when I asked if he could actually make a living from poetry, Armitage answered, “everything I do stems from the fact that I am a poet. But if I sheared away the prose and teaching and drama? Yeah, I would still get by.” According to figures published late last year by the magazine Mslexia, Simon Armitage was the tenth best-selling poet in the UK in 2013. Those 10 poets, however, included Dante, Homer, Seamus Heaney and Philip Larkin; among living poets, Armitage came third, behind the current poet laureate, Carol Ann Duffy, and Pam Ayres.

A week before the east London gig, we had met at Marsden station, a small stop tucked into the foothills of the Pennines, and drove through the village and out, round bend after bend, via Slaithwaite and Greetland, up to the top of the Pennine watershed. Armitage parked the car, and we stepped into a day of muted silvers: Blackstone Edge reservoir, pylons, a whited-out sky. Armitage, a tall man, walks as he speaks – unhurried, purposeful, with an unselfconscious physical confidence undented (or maybe underscored) by a period in his 20s when, diagnosed with an arthritic condition called ankylosing spondilitis, he thought he might soon not be able to walk at all. But it went into remission and these days he can walk for miles. In 2012, he published Writing Home, an account of an attempt to walk the Pennine Way backwards, from Kirk Yetholm to Marsden, where he was born, paying his way by reading poetry every night; Walking Away, in which he does the same, but from Minehead in Somerset to Land’s End, will be published on 4 June. It is the fourth, and, he says, the last in a series of wry memoirs (the others are Gig and All Points North) that achieve a distillation of what he ventures in his between‑poem patter at readings: open-seeming self-revelation, meditations on music and landscape and writing, about the meaning of various kinds of home.

In Gig, he described the tightrope walked by the touring poet: “A single human voice speaking a considered thought can feel like the high point of human achievement, or ... an object lesson in embarrassment.” Fame and achievement alter the balance, but not entirely; every move towards the mic still holds – as it should – an element of risk. “We’re all doing that, aren’t we?” Armitage said. “Every poet who ever stepped on to a stage or made some mark on a piece of paper is testing their reputation in some way. I have got to a point in my life and my career where I’ve stopped having to feel apologetic about what I do and why I do it. And actually I hear those noises coming from a lot of younger writers now. They don’t want to apologise. They want to get it out there and they want to be recognised and they want [poetry] to have a place in people’s lives and on their bookshelves and in their ears.”

From up here, on a good day, it is possible to see the Welsh mountains and Jodrell Bank telescope; Bolton and the beginnings of the Lake District; Littleborough, and Rochdale, where Armitage once worked as a probation officer. It would be glib to say this period is the reason for the undertow of darkness in his work, but it must have made its mark. Accidental death, affectless murder, suicide and loss stalk his early poems. He is drawn, in an increasingly prominent sideline of reimagined Greek dramas and medieval translations, to stories that face male violence head on. So Mister Heracles (After Euripides) features a viscerally detailed account of Heracles killing his family for the supposed greater good of the “mother state”; in Homer’s Odyssey, Armitage lingers over Cyclops’s bursting eyeball; The Last Days of Troy (produced at the Globe with supermodel Lily Cole as Helen last June) ends in an orgy of violence all the more shocking because it is so deliberately emptied of heroic justification. Armitage left the probation service after he had published four poetry collections and began to think he just might be able to make it as a poet. A surprisingly enlightened Home Office kept his job open for a year in case he foundered and wanted to come back. He never needed to, doing immediately as well, and better, than most poets could dream of – but the freelancer’s fear is not easily shaken. “I’ve only just got used to saying ‘No’,” said Armitage, “and I still don’t say it with much confidence. I don’t think people believe me, anyway.”

Last autumn, Faber published Paper Aeroplane: Selected Poems 1989-2014, a record of a 25-year career as a poet. “Normally when books come out I hardly take any notice of them,” he said. “I flick through to make sure they haven’t been printed upside down. But I always feel I want to move on or I have moved on and that’s been an issue for me – I haven’t really had time to enjoy a lot of things I’ve done.” But when this relatively slim volume arrived, he sat down with it on the end of the bed and stared at it for half an hour, reflecting, he said, on how the early poems in particular seemed “vivid and young, free and easygoing. Most of those original poems were written out of a desire to write rather than any notion they’d find their way into a book. I don’t think you can ever get that back.” They reminded him of an early life – as probation officer, as a homesick Portsmouth geography student who fled back to Marsden as soon as he was able – “that seems unrecognisable to me now”. As for the whole thing: “I think I felt pride, I don’t know if you are allowed to feel those things any more about your own work, but I did, I felt it was an accomplishment. So, yeah, I had a little moment” – he gave the phrase a camp, self-deflating turn, then laughed slightly. “But I’ve moved on now.”

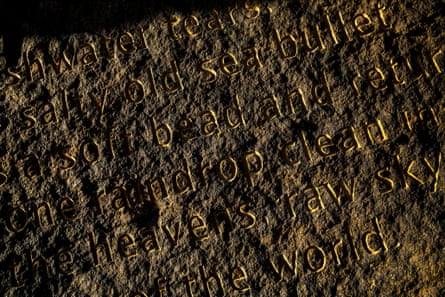

Up ahead, on a bend in the path, our destination appeared – an outcrop of Yorkshire gritstone so exposed to wind and rain whipping in off the Irish Sea that it has been chiselled into receding striations. At the base there is a flat section, with his rust-red words cut directly into the rock: “Be glad of these freshwater tears / each pearled droplet some salty old sea-bullet / air-lifted out of the waves.” The underlying colour of the rock was a surprise. “The first day I came up here after they carved it,” said Armitage, “it was really pissing it down. It was still quite raw, and it looked as if it was dripping fire.” There are six of these Stanza Stones along 40-odd miles of the Pennines, commissioned by the Ilkley literature festival as part of the Cultural Olympiad in 2012: an Armitage poem about manifestations of water (Snow, Rain, Mist, Dew, Puddle, Beck) is carved into each one. This stone, Rain, is the only one it is possible to happen upon accidentally; the presence of the poet is an occasional bonus. Two cyclists approached, swept past. “There you go. Oblivious. I think they actually accelerated.” Then a scraggle of chattering ramblers. We both waited – he, it seemed to me (although I could have been wrong) nonchalantly pretending he wasn’t – for at least one of them to stop, to recognise him, even. A couple glanced over, but they all kept walking. A short silence. “I’m sure they know it word for word.”

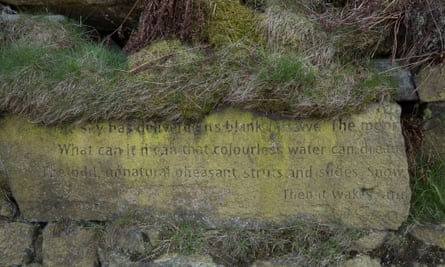

The second stone he took me to was quite different. Armitage parked along an exposed section of the A62 and we struck immediately, steeply upwards, on to the lower slopes of Pule Hill and a grassy track that led to an abandoned quarry. Many of the rocks here are shaped by man rather than the elements, into flat, near-black expanses, and, when we turned a corner at the top, into standing stones. It’s a chill place, a reminder of an old England of magic and tribal rites, the England Armitage accesses in poems such as Five Eleven Ninety Nine, where a present-day group of men feed and feed and feed a night-time bonfire until there is almost nothing left in the village. “It does feel like there is something malevolent and almost occult about it,” said Armitage, who used to come up here as a boy, even though it terrified him. His poem Snow is tucked into a crevice, lichen already reclaiming the letters.

Far below us the traffic roared; beyond the road the moors climbed into the sky. In All Points North, Armitage is clear about the importance of this landscape to his imagination. “I think I was aware you always had a choice,” he said. “You can get in the car and turn left into Huddersfield or Leeds or Sheffield, but you can turn the other way and you are not going to meet anybody all day and you can invent what those places mean. They are a kind of canvas or a blank page. Space beyond space and space after that as well, right up to the Cheviots and through Scotland.” All Points North was also his attempt to characterise – rather than define – the north, “where England tucks its shirt into its underpants”. When Armitage published it, in 1998, “there was a new confidence. A real sea change that had taken [the north] from the Roy Hattersley flat cap and whippets version to whatever it was I was describing, which is normality for me.” By the time he wrote Walking Home, 14 years later, it was “the height of the recession and so that was against the backdrop of communities really struggling to keep it together”. Perhaps the only constant, he said, is the growing economic gap between there and London.

And, for him, the cultural backdrop. In Gig he describes standing on West Nab, a point on the Pennine watershed six miles from Pule Hill, and looking out “across a huge circumference of inspiration and influence. Starting westwards it’s Manchester and Lancashire, so it’s Joy Division and the Fall, it’s the Smiths and Elbow, it’s Magazine and the Buzzcocks and Happy Mondays … Sheffield, which for me will always be the Comsat Angels, and maybe Pulp ... the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, which is Barbara Hepworth as a young girl in Wakefield, watching the dark horizon from her father’s car. Keep revolving further and it’s Larkin and Marvell, then Ayckbourn … Leeds is Bennett and Harrison and Henry Moore – and Bradford is Hockney and Priestley … further still there’s a line of wind turbines on the escarpment above Haworth, which is Brontë country. And a few more degrees brings Mytholmroyd and Hebden Bridge and Heptonstall … which is Hughes” – whose work, encountered at school, “lit me up” and made him a poet – “And which is Plath. Then I’m back where I started from, full circle, looking north. Wordsworth, maybe, on a clear day, if the eyes could see that far.”

Armitage did not want to be interviewed at his own house, apparently because a journalist warned him against allowing this particular intimacy years ago. The stricture didn’t apply to his parents’ house, however, and so we climbed down the hill and drove round to theirs (that “end of terrace” in Zoom!), for a cup of tea. Rather in the way that Armitage’s tight local focus has delivered an international audience, so the house he grew up in, tiny in front, tiny inside, opened on to a tiny patio with a vast view. Below us the land dropped away, into Marsden – terraced cottages, relics of the wool and textile industry, all loured over by a huge derelict mill – and then climbed up again, back into the moors. His tiny bedroom, on the first floor, had a window that looked out on all this. “That window,” he wrote recently in Poetry Review, “became the template for all my future poetry, an almost literal frame, which mimicked the shape of the page and provided a perspective through which I continue to see not just the village but life and the world.”

Armitage’s father is “a born exaggerator”, a barbershop singer and amateur actor once described by his son as “leaning forward into the applause as if it were sunlight on his face”. He was already a probation officer when Armitage went into the trade, and reportedly rather put out when his son retired before he did. Armitage gets a fair amount of prose mileage out of his father’s witty reactions – to the first appearance of the earring he still wears, to the announcement that he was a poet – but the knockabout is moderated by obvious care and respect, and as we settled on to the patio, in bright sunshine, Armitage leaned back and simply let his father perform. When he did speak, it was as his father does, in a Yorkshire accent far broader than is evident the rest of the time.

Dialect and deliberately northern inflections are central to both the music and the politics of Armitage’s poetry. “Poems are all about signalling,” he often says in question and answer sessions after readings. “We live in a world where as soon as you open your mouth you are pretty much nailed. [People] know you not just horizontally and cartographically, they know you vertically as well, where you stand in the class structure, what your parents did, where you went to school. And I think writers are very aware of that and play with it” – as he does, by sticking the word “mush”, meaning face, into a formal sonnet, for instance. One of the many reasons he chose to translate the medieval poem Gawain and the Green Knight (2007) was that the anonymous poet obviously came from the same part of the world, and Armitage felt an affinity with the words he used, the landscape and rhythms. The translation did well, selling 35,000 copies so far, despite earning Armitage a rap on the knuckles from the eminent critic Frank Kermode, for the “naughtiness” of his frequent modernisms and anachronisms (“I kid you not”; “bum-fluffed bairns”) and occasional ad-libbing.

His mother arrived, and stood looking over the scene. Both parents are 80 now, and while his father claims to be perfectly happy where he is, his mother obviously has a hankering to travel – “Lake Como,” she said, pointedly, looking at her extremely well-travelled son. When Armitage did his walk down the Pennine Way, he was psychologically hampered, as one critic put it, by the fact that she had done it before him, at about 50. His mother worked as a non-teaching assistant at a couple of infant schools; his father, trained as a plumber, worked as a tyre salesman and, as his son once said, as “a bit of a free agent and wheeler-dealer” before fetching up in the probation service. Often there wasn’t much money; sometimes, Armitage suspects, none at all, though “I don’t remember that anxiety being passed on to us.”

“I remember when something new came into the house,” he had said to me earlier that morning. “It was astonishing. Like a vase. Or god forbid a settee. We’d sort of stand round it and gawp at it.” In Armitage’s poetry, objects are described with surprising exactness, partly for their own sake, partly for their roles in (often male) ceremonies and processes – and partly as instant metaphors. “Most objects speak volumes about their social value.” In his work the language of objects allows, at its best, complex, unspelled-out layers of social commentary, and shows, at its least, a sophisticated knack for lists.

John Updike once suggested that he was prolific because he treated writing like a nine-to-five job, rather than a fitful process of waiting for a muse; that he and others like him, such as Joyce Carol Oates, were “blue-collar writers”. Armitage, whose bibliography now includes 21 books of poetry, five of non-fiction, two novels, 21 films, many radio plays, and five works for theatre (not to mention the fact that, with his wife Sue Roberts, he performs in an eight-person band called the Scaremongers), is undeniably prolific, to an extent that seems to provoke suspicion in the literary world: if you produce that much, with such fluidity, it cannot possibly be good. “I definitely don’t think of it as a job,” said Armitage. “I had a job once and I got rid of it. But I completely understand that idea of coming from a working-class background and wanting to get on with something. There is a sort of satisfaction in being self-employed or self-made, homemade.” The Armitage household is one of enthusiasms: music, cricket, astronomy, birdwatching, art, walking, and acting – lots of acting. Armitage Senior’s all-male pantomime (he is writer and director) is so popular that it is always sold out way ahead of Christmas; in Marsden, he is the undisputed star, not his son. Back in his home town, Armitage Junior’s success, anywhere in the world, is still measured in terms of the capacity of the local Parochial hall – “2.5 Parochial halls? Not bad.” Hence, perhaps, his gregariousness, his tendency to hang poems on a story or a fragment of story, his ease with performance: tell a tale, a yarn, grab your audience by the collar and drag them along with you – a disposition that achieves a kind of zenith in the brilliant, moving prose poems of his 2010 book Seeing Stars.

But gregariousness, humour and ease, while alluring, are not the same as emotional availability. An attempt to ask about his first marriage – the subject of unusually personal poems in his fourth collection, The Book of Matches – was swiftly shut down. “You were married before,” I begin. “Was I?” There are distancing devices everywhere in the work: the emphasis on stories and concrete things can push the focus outward rather than inward, and a performer doesn’t have to display feelings he doesn’t choose to. “He’s guarded,” said Maxwell, who has fond memories of often quite silent walks through Iceland. “Everyone should be. His public person is certainly not fake. It’s an authentic public persona. He knows the difference and he guards the border.”

After we left his parents, Armitage gave me a tour of Marsden: the Parochial, the school, the bust of Samuel Laycock (the village’s other famous poet) overlooking the playground. When we stopped for lunch, sloppy sandwiches on a bench in the main square, family acquaintance after family acquaintance walked past, saying hello. Suddenly it all became too much. “It feels like being in the Truman Show,” said Armitage. “Let’s go.” But not before a middle-aged man came up to him. “Mr Armitage?” Yes. “Great reading you.” Thank you. “Now, I’ve been trying to get tickets to your father’s pantomime …”

On stage in London, Armitage introduced another poem. “I think every poet at some stage in their writing life should try and write the definitive home-town poem. With Huddersfield, that was difficult. I didn’t really know what to lock on to as a coordinate. I eventually felt that the one thing that was most authentic were these synthetic – sort of Tudor – coffeehouses.” Laughter. “They’ve even proliferated into Halifax.” The laughter built. “There’s a drive-in! Ye olde drive-in coffee-house.” The poem is addressed to the “women of the Merrie England Coffee Houses”, in a tone that is insistently physical, both sexual and respectful of them as mothers, from the remembered point of view of a young Armitage and his friend, “the boy Smith”, who spent afternoons in those coffeehouses, grateful to be allowed to eke out “one toasted teacake between us” as they tried to write. “O women of the Merrie England, under those scarlet aprons, are you naked?” “He’s writing about a world he loves,” says Jeremy Noel-Tod, a poet and academic who has followed Armitage’s work for 20 years. And while Armitage is never going to express emotions in a high-blown way, that does not mean they are not there: that gratefulness; the fact – delivered in an aside – that the Boy Smith’s mother fell asleep at the wheel. “There’s a grief that’s not being talked about here – I think that’s really part of the Englishness of his work. He’s very good at talking about how things are not talked about.” It’s a tricky thing to pull off, and while the poem veers close to objectification, it works, in the end. The audience sighed, appreciative.

When we had finished in Marsden, Armitage drove me into Huddersfield to take the train, and, while we were waiting, to a Merrie England Coffee House (via a building topped by a fibreglass lion about which he has also written a poem) for a cup of tea. I could see how it was, once, how much it meant, the permission given and the start made; but also just how much has changed since. In his statement of candidacy for professor at Oxford, Armitage wrote that he would use the post “to discuss the situation of poetry and poets in the 21st century, to address the obstacles and opportunities brought about by changes in education, changes in reading habits, the internet, poetry’s decreasing ‘market share’, poetry’s relationship with the civilian world and the (alleged) long, lingering death of the book.” When he walked the Pennine Way, doing a gig a night, for Walking Home, he made much of the fact that he was testing the health of poetry in general – was it even alive? Would people come? All it really tested, I suggested, is how well Armitage, specifically, is doing. He bristled. “No, I disagree. In some of those places people didn’t know who I was but they came along to listen to a poetry reading. And anyway, even if they did know it was me, it’s still poetry.”

No comments:

Post a Comment