|

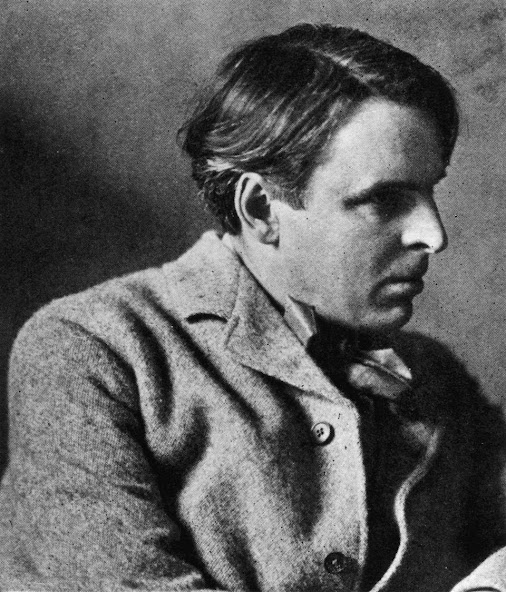

| W.E.Yeats |

‘For a further union’: Conceptions of Unity in the Later W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot

Charika SwanepoelAbstract

This paper considers the shared preoccupation with unity in the later works of W.B. Yeats and T.S. Eliot with the aim of emphasizing the likeness in their thinking despite their vastly different theological stances. The unity strived for by both poets involves a dedicated resolution or transformation of contraries. Yeats scholars such as George Bornstein have termed Yeats’s dedication to all things opposite his ‘antinomial vision’ and Eliot scholars such as Jewel Spears Brooker refer to Eliot’s ‘dialectical imagination’. This paper is aimed at further developing the established view of these comparable tendencies by pointing to a three-part pattern that emerges from Yeats and Eliot’s later works. This pattern suggests a similar process behind their ‘antinomial vision’ and ‘dialectical imagination’ that entails: 1) a concern with opposites, 2) an ensuing inarticulacy, and 3) a capacity for incarnation. While this paper analyses Yeats and Eliot’s individual contributions, it draws broad philosophical patterns between them and illustrates the similarities and parallels that incidentally emerge from the comparison.

Introduction

Yeats and Eliot grappled with similar Modernist problems, albeit from different vantage points. In particular, both poets assumed a deeply theological approach to the Modernist crisis. Indeed, among the Anglophone poets who contended with religious and transcendent questions in the years surrounding the Second World War, Yeats and Eliot stand out. Both poets understood the relation between history and eternity as ‘a question of theodicy’ (Soud 3). However, the two poets differed significantly in the theological substance that informed their thinking. While Eliot is most often associated with Anglo-Catholicism, Yeats’s exploration of religious beliefs was more varied, constantly drawing on different sources. The stark difference in their theological stances also influenced their view of each other. Of Yeats’s early style, for instance, Eliot wrote: ‘you cannot take heaven by magic, especially if you are, like Mr. Yeats, a very sane person’ (CP V4 697). Yeats and Eliot’s unsteady literary reception of the other’s verse is best outlined by John Kelly in his essay on the two poets in the 2016 Yeats Annual (No. 20). While the scepticism with which Eliot and Yeats viewed each other waxed and waned, it is this perspective that often deters critics from reading them alongside one another. Yet, in his analysis of their literary relationship, Kelly hints at a connection ‘between Yeats’s quest for Unity of Being and Eliot’s nostalgia for an undissociated sensibility’ (186). It is this notion that the present paper explores more closely by comparing Yeats and Eliot’s use of opposites as the instruments of unity. Where the questing after unity is concerned, they are often more alike in their thinking than is commonly accepted. In their later works, both poets aspire to create what is otherwise lacking in modern life through what is often a three-part process. In this paper, I propose that this process includes: 1) a concern with opposites, 2) an ensuing inarticulacy, and 3) a capacity for incarnation. The close readings that follow identify this process in Yeats’s ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul’ and Eliot’s Four Quartets, with an emphasis on ‘Little Gidding’.

Antinomies and Dialectics

While Yeats and Eliot’s interest in opposites is well-documented, I frame it here as part of a larger religious and/or transcendent process. To date, Yeats scholars have come to know the poet’s predisposition as his ‘antinomial vision’ (Bornstein 382) or his adherence to a ‘Blakean model of conflict and discord’ (Cuda 58). Yeats was continually attracted to the theme of opposites and the tensions they revealed. In a letter to Ethel Mannin, only a year prior to his death, Yeats tells of his ‘private philosophy’: ‘To me all things are made of the conflict of two states of consciousness, beings or persons which die each other’s life, live each other’s death’ (‘Letters’ 918). A dynamic dialectic is activated by consciousness seeking after an opposite. Bornstein argued that Yeats’s antinomial vision lies in ‘accepting the full dialectic, not merely half of it’ (Bornstein 384). I would go further and suggest that Yeats’s vision emphasized not just the acceptance of the full dialectic but the sequential and intentional pursuit of the full dialectic. This pursuit is perhaps best exemplified by Yeats’s conceptualization of the Daimon, which he believed to be ‘our autonomous opposite, which bore within itself the weight of all that we are not but desire to be’ (Meihuizen 1). While Yeats’s conception of the Daimon would develop over time, consider the poem ‘Ego Dominus Tuus’ in which one of the antinomial characters in the poem, Ille, calls up his own opposite in so many words: ‘By the help of an image / I call to my own opposite, summon all / That I have handled least, least looked upon’ (CW1 161). To this, Hic replies: ‘And I would find myself and not an image’ (CW1 161). This call, then, serves as something of a conjuring of the persona’s Daimon whose appearance will result in the energy that emanates from the meeting of contraries.

This dedication to opposites is at the core of what Yeats would later refer to as Unity of Being. From the Automatic Script sessions held by Yeats and his wife, George Hyde-Lees, comes this description of Unity of Being: ‘Complete harmony between physical body, intellect & spiritual desire … ’ (Mills Harper & Paul 237 n46). Uniting the aspects of one’s being involves an inner harmonization of concepts often perceived to be opposites (e.g., physical/spiritual). However, as Yeats’s ideas surrounding Unity of Being developed, he came to a deeper understanding of the concept, even identifying it as his Christ. In 1937, Yeats articulates this faith as follows:

I was born into this faith, have lived in it, and shall die in it; my Christ, a legitimate deduction from the Creed of St. Patrick as I think, is that Unity of Being Dante compared to a perfectly proportioned human body, Blake’s ‘Imagination,’ what the Upanishads have named ‘Self’: nor is this unity distant and therefore intellectually understandable, but imminent, differing from man to man and age to age, taking upon itself pain and ugliness, ‘eye of newt, and toe of frog’ (‘Introduction’ 210).

Eliot scholars have identified a similar dedication to opposites in his poetry. Most notably, Jewel Spears Brooker sees the movement of Eliot’s mind as a pattern involving ‘a play between opposites that moves forward by spiralling back (a return) and up (a transcendence)’ (3). Like Yeats, Eliot is informed by the various philosophies of his time. These influences include, among others, philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and F.H. Bradley, along with Eliot’s Indic studies. Eliot’s conception of opposites and their role in the quest for unity is particularly philosophical, even academic. As part of a graduate seminar at Harvard University, for instance, Eliot wrote three papers on Kantian Philosophy in which he advanced ‘pieces of a provocative and sophisticated theory of opposites’ while trying to find the ‘corrective to Kant’s absolute distinctions’ (Brooker and Charron 48). Eliot’s ideas began to take on a relativism that argues against contradictions or contraries and sees opposites as correlative and relative to one’s point of view.

While writing his Ph.D dissertation on F.H. Bradley in 1915 and 1916, Eliot engaged with a principle not dissimilar to Blake’s undivided ‘Universal Mind’ – Bradleyan epistemology. Bradley divides knowledge, as experience, into three levels: immediate, relational and transcendent (Brooker 184). First, much like Yeats’s description of Unity of Being that is not ‘intellectually understandable, but imminent’ (‘Introduction’ 210), Eliot perceives Bradley’s immediate experience as experience that ‘has not been mediated through the mind’ (Brooker 184). In Eliot’s dissertation, Knowledge and Experience in the Philosophy of F.H. Bradley, he describes immediate experience as ‘a timeless unity which is not as such present either anywhere or to anyone. It is only in the world of objects that we have time and space and selves’ (31). This phrasing is reminiscent of Yeats’s description of Blake’s belief that consciousness was ‘originally clairvoyant’ but shrinks ‘under the rule of the five senses, and of argument and law’ (‘The Works of William Blake’ 77). Bradleyan immediate experience, like Blake’s Universal Mind, then, is the undifferentiated condition Eliot refers to as ‘the starting point of our knowing, since it is only in immediate experience that knowledge and its object are one’ (‘Knowledge and Experience’19).

Only once mediated through the mind do we encounter relational experience, the second of Bradley’s levels of experience. Once we distinguish ourselves from our surroundings and our surroundings from each other through comparison and division, immediate experience dissolves ‘into the dualities of the intellect’ (Brooker 158). This is experience akin to Blake’s teaching of the separation of the one mind into sets of opposites, a separation likened to the fall of man. Relational experience is where Yeats and Eliot, and all Modernists, start from – a world of binaries and absolutes. However, the final level of Bradleyan experience, transcendent experience, ‘permits a return of sorts to the wholeness and unity of immediate experience’ (Brooker 186). This return is not a return to a state prior to existence, a reversal of knowledge and experience, but refers to informing immediate experience with the intellect of relational experience. In this sense, transcendent experience can be interpreted along the same lines as Yeats’s description of Blakean consciousness, as ‘the result of the divided portions of Universal Mind obtaining reception of one another’ (‘The Works of William Blake’ 77). Similarly, in A Vision (1925), Yeats writes: ‘when … the Daimonic mind is permitted to flow through the events of his life … and so to animate his Creative Mind, without putting out its light, there is Unity of Being’ (AVA 26). Another resemblance can be drawn between Yeats’s use of the term Unity of Being and Eliot’s use of the term ‘unity of consciousness’ in the following passage from Knowledge and Experience detailing Bradley’s ‘finite centres’:

The point of view (or finite centre) has for its object one consistent world and accordingly no finite centre can be self-sufficient, for the life of a soul does not consist in the contemplation of one consistent world but in the painful task of unifying (to a greater or less [sic] extent) jarring and incompatible ones, and passing, when possible, from two or more discordant viewpoints to a higher which shall somehow include and transmute them. … Wherever, in short, there is a unity of consciousness, this unity may be spoken of as a finite centre (147–48).

Every phase is in itself a wheel; the individual soul is awakened by a violent oscillation (one thinks of Verlaine oscillating between the church and the brothel) until it sinks in on that Whole where the contraries are united, the antinomies resolved (AVB 89).

He who attains Unity of Being is some man, who, while struggling with his fate and his destiny until every energy of his being has been roused, is content that he should so struggle with no final conquest … such men are able to bring all that happens, as well as all that they desire, into an emotional or intellectual synthesis and so to possess not the Vision of Good only but that of Evil. (AVA 26)

Of the Inarticulate and Incarnation

Some of the most pertinent examples of Yeats’s antinomial vision in his later poetry occur in poems with a tête-à-tête tone and style, such as ‘Ego Dominus Tuus,’ ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul,’ sections of ‘Vacillation’ and ‘Man and the Echo’. In ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul,’ for instance, ‘My Soul’ and ‘My Self’ are caught in a dramatic exchange in which Self gets the last say in an astonishing four-stanza reply that embraces the continual ‘crime of death and birth’ (CW1 239). Like Yeats’s description of those who attain Unity of Being in A Vision – ‘content that he should so struggle with no final conquest’ (AVA 26) – Self is ‘content to live it all again’ (CW1 240). The poem celebrates, as it were, the incarnation that lies in the pursuit of opposites.

Throughout the poem, ‘My Soul’ emphasizes a gyre-like ascent and ‘the winding ancient stair,’ leading to a ‘quarter where all thought is done’ (CW1 238). Since such an envisioned quarter is devoid of thought and since Yeats would consider – via Blake – thought the great divider of all things into antinomies, we may interpret the gyre-like ‘ancient winding stair’ to be symbolic of the dynamic, and spiraling, quest for Unity of Being. Yet, in ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul,’ Yeats poses the questing for Unity of Being against what appears to be Unity of Being itself, what is referred to in the poem as an ‘ancestral night’ that resembles Blakean undividedness and even Eliot’s conception of Bradleyan immediate experience. Soul urges Self to set aside imagination and wandering and, instead, contemplate the deliverance of ‘ancestral night’:

From the struggle with opposites, an inarticulacy must surely emerge. When drawing opposites together, language can no longer suffice since language itself differentiates. Both Yeats and Eliot express an awareness of the limits of language following their pursuit of unity. Both aim at describing what is indescribable; this second aspect in the three-part process of embodying unity nevertheless takes literary form. While partly due to their difference in style, Eliot dedicates a greater quantity of text than Yeats does to what is referred to in ‘East Coker’ as ‘a raid on the inarticulate’ (CPP 182). In fact, Eliot addresses the difficulty with language in each of the poems in Four Quartets. This much is to be expected from a set of poems teeming with opposites presented by Eliot as paradoxes. Consider the very first lines of the first quartet (‘Time present and time past / Are both perhaps present in time future’ (CPP 171)) and the last line of the last quartet (‘And the fire and the rose are one’ (CPP 198)). From start to finish, then, Eliot arranges words designed to divide in such a way that they gather, if not unite. Unlike Yeats’s stoned tongue in ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul,’ Eliot’s struggling with words to express unity is active. This movement is evident from the first of the quartets:

There is no absolute point of view from which real and ideal can be finally separated and labelled. All of our terms turn out to be unreal abstractions, but we can defend them, and give them a kind of reality and validity … (Knowledge and Experience 18).

Conclusion

Yeats and Eliot certainly have in common the search for a transcending wholeness. As this paper has shown, Yeats’s conception of Unity of Being is shaped by his wide-ranging study of esoteric and religious literature while Eliot’s sense of unity is largely informed by his philosophical and religious sensibilities. Both poets actively pursue opposites and contradictory conditions in an attempt to embody in their poetry what they perceive to be a greater unity. To Yeats, this is Unity of Being, and to Eliot, this is ‘the impossible union / Of spheres of existence’ (‘Dry Salvages’ CPP 190). The examples outlined here suggest that Yeats is predisposed to embodying his conception of Unity of Being through images and symbols as aspects of the poet’s Imagination, which, in Blakean terms, (re)connect the divided portions of the Universal Mind. Eliot’s Four Quartets illustrates his efforts to embody his conception of unity through language itself, through engaging with opposites in a medium not conducive to the unity of ‘one consistent world’. Most importantly, both Yeats and Eliot conceive of a unity that can or should only be pursued and not fully attained in life. In ‘A Dialogue of Self and Soul,’ for example, continued incarnation through the pursual of opposites is actively chosen: ‘I am content to live it all again … I am content to follow to its source / Every event in action or in thought’ (CW1 240). Likewise, opposites and their connections must be dutifully pursued in Four Quartets not through Imagination or art as Yeats would have it, but through ‘prayer, observance, discipline, thought and action’ (CPP 190).

Notes

1 See Swanepoel (OLH, 2022) for an analysis of the sources that inform Yeats’s conception of Unity of Being. Also see how this passage relates to the Creed of St. Patrick in Kathleen Raine’s chapter ‘Yeats and the Creed of Saint Patrick’ in Yeats the Initiate (Barnes & Noble, 1990).

2 Also see Yeats’s 1924 essay ‘William Blake and His Illustrations to The Divine Comedy’: ‘Our imaginations are but fragments of the universal imagination, portions of the universal body of God, and as we enlarge our imagination by imaginative sympathy, and transform with the beauty and peace of art the sorrows and joys of the world, we put off the limited mortal man more and more and put on the unlimited “immortal man”’ (103).

Works Cited

- Bornstein, George. ‘The Aesthetics of Antinomy’. In Yeats’s Poetry, Drama, and Prose: A Norton Critical Edition. Edited by James Pethica. New York: Norton, 2000. 382–386. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker, Jewel Spears. Mastery and Escape: T.S. Eliot and the Dialectic of Modernism. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker, Jewel Spears and William Charron. ‘T.S. Eliot’s Theory of Opposites: Kant and the Subversion of Epistemology’. In T.S. Eliot and Our Turning World. Edited by Jewel Spears Brooker. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2001. 47–62. [Google Scholar]

- Cuda, Anthony. ‘W.B. Yeats and a Certain Mystic of the Middle Ages’. In Julian of Norwich’s Legacy: Medieval Mysticism and Post-Medieval Reception. Edited by Sarah Salih and Denise Baker. New York: Macmillan, 2009. 49–68. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns. The Complete Prose of T.S. Eliot. The Critical Edition. Volume 4: English Lion, 1930–1933. Edited by Jason Harding and Ronald Schuchard. Johns Hopkins UP and Faber & Faber, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns. Knowledge and Experience in the philosophy of F.H. Bradley. London: Faber & Faber, 1964. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Eliot, Thomas Stearns. The Complete Poems & Plays of T. S. Eliot. London: Faber & Faber, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly, John. ‘Eliot and Yeats’. In Yeats Annual No. 20: Essays in Honour of Eamonn Cantwell. Edited by Warwick Gould. Open Book Publishers, 2016. 179–227. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Meihuizen, Nicholas. Yeats, Otherness and the Orient: Aesthetic and Spiritual Bearings. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mills Harper, Margaret and Catherine Paul. ‘Notes’. In The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Volume XIII: A Vision (1925). Edited by Margaret Mills Harper and Catherine Paul. New York: Scribner, 2008. 213–338. [Google Scholar]

- Soud, David. Divine Cartographies: God, History, and Poiesis in W. B. Yeats, David Jones, and T. S. Eliot. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2016. [Crossref], [Google Scholar]

- Swanepoel, Charika. ‘Three Sources of W.B. Yeats’s Syncretic Christ: Dante, Blake and the Upanishads’. Open Library of Humanities 8(2), 2022: 1–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.6318 [Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. ‘Introduction (1937)’. In The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Volume V: Later Essays. Edited by William O’Donnell. New York: Scribner, 1994. 204–16. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. ‘Introduction to “Mandukya Upanishad” (1935). In The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Volume V: Later Essays. Edited by William O’Donnell. New York: Scribner, 1994. 156–64. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. The Letters of W.B. Yeats. Edited by Allan Wade. London: Rupert Hart-Davies, 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Volume I: The Poems. 2nd ed. Edited by Richard Finneran. New York: Scribner, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. ‘Preface (c. 1892) to The Works of William Blake: Poetic, Symbolic, and Critical (1892)’. In The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Volume VI: Prefaces and Introductions. Edited by William O’Donnell. New York: Scribner, 1988. 74–79. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. A Vision (1937). New York: Macmillan, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Yeats, William Butler. ‘A Vision’ (1925). In The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Volume XIII: A Vision (1925). Edited by Margaret Mills Harper and Catherine Paul. New York: Scribner, 2008. 1-211. [Google Scholar]

No comments:

Post a Comment