|

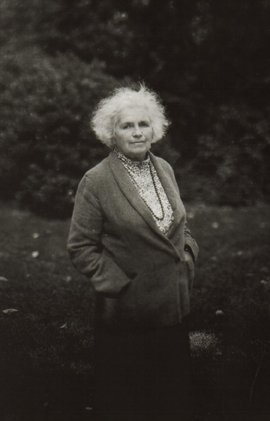

| Grace Paley |

An Interview With Poet and Fiction Writer Grace Paley

Celebrated short story writer and poet Grace Paley died of cancer last August at the age of eighty-four. A lifelong activist, pacifist, and an early figure in the women’s rights movement in the 1960s, Paley was one of those writers who managed to combine a public life of frequent readings and appearances in support of a range of causes with work lauded for its artistic integrity. A familiar figure at writers conferences and rallies against, over the years, the war in Vietnam, nuclear proliferation, apartheid in South Africa, and the Iraq War, she was tireless in her efforts to bring injustice to light. As one of the first American writers to explore the lives of ordinary women in her work, she broke ground and served as a role model for women writers who came of age in the ‘60s and ’70s. In her writing and activism, she achieved something rare, a life in which the public persona and the private person were one.

Grace Paley was born in the Bronx on December 11, 1922, the daughter of Russian Jewish immigrants. Though she began her writing life as poet, she found the voice for which she would be known when she started writing fiction in her thirties, drawing heavily on her childhood in the Bronx and her experiences in her neighborhood in Greenwich Village. She published three volumes of short stories that established her as a master of the form: The Little Disturbances of Man (Doubleday, 1959); Enormous Changes at the Last Minute (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974); and Later the Same Day (FSG, 1985). In 1994, FSG published her Collected Stories, which was a finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. She is also the author of a collection of essays, Just As I Thought (FSG, 1998) and a number of volumes of poetry, including Leaning Forward (Granite Press, 1985) and New and Collected Poems (Tillbury Press, 1991). This month, FSG will publish her final poetry collection, Fidelity, which she completed just before her death. Paley lived in Manhattan and Thetford Hill, Vermont. She taught at Sarah Lawrence College and the City College of New York. From 1986 to 1988, she was New York’s first State Author and from 2003 to 2007 served as the Poet Laureate of Vermont.

We interviewed Paley a little more than a year before her death at her home in Thetford. Arriving at the appointed time, we got no answer when we knocked on the door. We drove back down the steep dirt road to town and found her husband, Bob, in the yard of his son’s house. He asked if we had tried the door. It was unlocked, and Grace was there, taking a nap. “Go inside and wake her up,” he told us. We drove back up the hill and walked into the house and woke her up. She had been sick then for a year with the breast cancer that would take her life, but she entertained our questions with her characteristic wry humor and quick wit. In the last year of her life, Paley continued to give readings and to make public appearances when she could. She remained a vital presence and an inspiration.

Poets & Writers Magazine: You have spent much of your life protesting against war. How does it feel to be protesting again, with the war in Iraq?

GP: I never expected I would really change the world. I do a lot less protesting now because I’m not that well. But I can put it this way: I think the world is worse, but the people are better. I think this has to do with the revolutions of the 1960s and ’70s and the work we all did in that period. The important thing to remember about the Iraq war is that the whole world protested against it. For the first time in history, the whole world, not just me and my husband Bob, but the whole world came together to try to stop a war before it started. That had never happened before. I have a book with pictures of those protests from all over the world, from Africa, from Asia, from all over Europe. In every country people said, “No, no, don’t do it, don’t do it.” Whatever happens now, this fact is in the world. I think with those protests, we made maybe a couple of inches of progress. Some light flared there for a minute and that minute may be carried on. That’s why I say the world right now is a little worse, mostly because of what our country is doing, but the people are better because almost everywhere in the world there are people who are really thinking that they have some responsibility to make a peaceful world and to live decently. We’ll see what the next generation can do.

P&W: You have often said that you’re an optimistic person. How do you feel about social action? Are you still optimistic about the possibilities for creating social change?

GP: I’m optimistic because of that one moment when the whole world came out against the war. That has made me optimistic, but apart from that, I have a lot of anxiety about the state of the world. When you think of the things that have happened in Rwanda and Darfur, that are still happening in Darfur, it’s very discouraging. The degree of just plain murder is incredible. What’s happening in Iraq, where they’re all killing each other, is just terrifying. I’m neither optimistic nor pessimistic; I’m just on my knees hoping that things change somehow.

P&W: Do you think it’s important for writers to be socially active?

GP: Writers? I advocate plumbers should also do something, everybody should do something. When the Iraq war started, Sam Hamill from Copper Canyon Press got all these poets together. Before anybody said a word, he had ten thousand poets writing letters to the White House saying, “Don’t go into Iraq, don’t go in.” The writers were on top of it. I have no complaint about the writers. During the Vietnam War we had something called Angry Arts, which Bob and several other artists organized. For a whole week all the artists performing in concerts at Town Hall and Lincoln Center stopped and got up and turned their backs. Everybody was quiet for several minutes to make the statement we are against this war. Artists were making murals all over the city, and the poets were in trucks driving around reading poems. The artists were present. But everybody should be involved, not just the artists. Carpenters, teachers, everybody.

P&W: In one of your essays, you tell the story of when you went to Hanoi in 1969, and one of the young Vietnamese in the group was upset to hear the Americans criticize their country. He said, “Don’t you love your country? What about Jefferson and Emerson and Whitman?” What is it like for you to have difficulty loving your country and how have you handled this over the years?

GP: First of all, it was this dopey guy in our group of Americans who made these remarks. I can still see him saying, “Oh, you wouldn’t like to come to my country, it’s racist, you know.” And I thought I’d die. I wasn’t about to get up and say my country is not racist, but I thought, “You idiot.” Then this young fellow, this young Vietnamese man, comes and says, “Are you crazy, how can you talk about your country like that?” And then we did talk more about it. Well, I’m an American. I don’t feel national pride or anything like that, but on the other hand I’m very interested in this country. I’m very interested in the history of it, and I feel that it does have some valuable ideas that really have transformed many people. Certainly this is true when I think of my own parents coming here and all the other immigrants who have come here. They came for a reason, and they were satisfied, one way or the other.

My mother says she still remembers standing at the boat in 1905. The pogroms in Russia were terrible in 1904 and 1905. They started in the 1890s and they were terrible. The Jewish Forward had a piece about this a couple of years ago, looking back to 1905. They quoted from the accounts back in 1905 saying, “In the towns and in the villages, the slaughter has been immense.” So my parents came to this country. My father went to school immediately and learned Italian and English and became a doctor, and late in life became a painter, when he retired from being a doctor. My son said, “My grandfather is an artist retired from a doctor.” They did well. Not all immigrants have done equally well, but if you talk to Italians or Irish or Serbo-Croatians, the country welcomed them. Now we are unwelcoming to immigrants because they are a poor and undereducated class. The bad thing is these old time immigrants are not standing up enough for the newer immigrants—the Latino people who have been coming across the Mexican border and others. There are many different cultures in this country, which makes it a very interesting country.

P&W: In your book of collected writings, Just As I Thought, you describe your parents as “atheist, socialist Jews.” How much did their views influence yours?

GP: Yes, that is who my parents were, but I used to take my grandmother to shul. She was not an atheist, though she was not very religious. But the way my parents lived just seemed the normal way to live. I grew up in the Bronx. My memories are from the Depression, the late 1930s. The people on my street didn’t work then. The men had no work, but my father was the neighborhood doctor. So I was a rich person relative to all my friends. I had a very happy childhood because the streets of New York are wonderful for children. You’re free on the street as a child. In summertime, you could play on the street till ten o’clock at night. Your mother would look out the window or someone else’s mother and say, “Come on, come back up to the house.” Sometimes a kid would go and sometimes another half hour would pass. There was always somebody there on the street. There were always children to play with.

My family talked politics at the table. I mean it was a normal conversation. My father would read the paper and say, “Goddamn.” They talked Russian to my grandmother who might answer in Yiddish or Russian, but mostly by the time I was growing up they spoke English at home, though they read Russian. My father got a Russian Socialist newspaper of some kind.

P&W: At the end of many of your stories, there is the sense that life just goes on. There’s no particular ending to the story. Your character Zagrowsky says, “I tell you what life is going on, you have an opinion, I have an opinion, life don’t have no opinion.”

GP: That was true for my family. At suppertime there would be, if everybody was there, my father and my mother, who were social democrats and very upset about the Soviet Union. Then there would be my aunt who was a communist, and my other aunt who was a zionist. There were big differences of opinion. They would talk and talk, and life went on no matter what.

I still remember my mother reading the newspaper at the table when I was a kid. Apparently the Nazi party has just gotten itself together, and Hitler is in power. It must be around 1939, maybe a little earlier. My mother says to my father, “Look, Zenia, it’s beginning again.” Those words— “it’s beginning again”—have reverberated in my ears all my life. It’s beginning again. The fear you hear in those words. As a person who has never really suffered any prejudice, I remember those words.

I have letters from 1912, 1914, in Russian, from a woman writing to my aunt Yuba. The woman writes, “I don’t know what to do about the boys. I don’t know what to do with the two of them. They’ve gotten some foolishness in their head. They are going to some farm and taking classes to learn how to be farmers. They want to go to Palestine. I tell them they can’t, they mustn’t do it, and they say, ‘But what have we here? We have nothing here.’” They’re right, she says, they have nothing here. There’s nothing here for them, and so, she says, I have to let them do what they want. But why do they want to be farmers? She’s horrified. What’s wrong with these children? They want to be farmers? In Palestine of all places?

P&W: There is such a strong, almost spoken voice to your stories. It feels like you are sitting there telling me the story. How did you discover this voice?

GP: I read a lot. In poetry, I liked W. H. Auden more than anyone. I loved British writers and the novels I grew up with, Twain, Dickens, and so on. I was not influenced say by Walt Whitman or anyone like that. His freedom was not my freedom, and so it didn’t affect me. But Saul Bellow had begun to write already. He freed the Jewish voice in some ways that I didn’t even recognize, but his work was all about men. Still, for Jews who are crazy about the English language, he was the one.

My father must have told us Bible stories, because I had Biblical stories bred in me from early on, and I don’t know from where. It wasn’t my grandmother so much. I am very interested in the Bible. It’s the King James version that I know, which is also great English literature. I think it had an effect on me because I’ve read the Bible a lot. I love the style of the King James Bible more than anything else. I was always a big reader, and I read good literature. The reason I mention this is because I keep telling students, “You’ve got to read.” We have a great tradition in English literature. We’re very lucky. We have this big English language, which is so receptive of other languages. English takes everything in. The French have laws that you can’t say this, you can’t say that, but in English you can say any god-damned thing you want, you know.

P&W: You began to write prose relatively late. You had been writing poetry before that. What was it that led you to start writing prose?

GP: Well, I’ll tell you, something funny happened to me. I thought I’d like to try to write stories, and it turned out that I had a lot of subject matter, which I didn’t realize at first. At first I just had the first story I wrote. I was amazed when I finished it. I couldn’t believe it. I suddenly had this large subject matter of the lives of women. I found this subject matter because I’d been spending much of my days with women and children in a way that I hadn’t before, in Washington Square Park mostly.

You see, nothing happens without political movement. Now it just so happens that when I started writing prose, the women’s movement was coming together. I didn’t know this. What happens is that you’re part of something without knowing it. The black power movement had a literature that lived with it, that supported it. So the women’s movement began to develop. Tillie Olson and I didn’t know it, but we were part of a movement. I became more and more interested in the lives of women, and I couldn’t write about this in poetry. I didn’t know how to write about this material in poetry. I can now, but I couldn’t do it then. So I had these stories, and I began to write them. I wrote them slowly over fifteen, twenty years. Really not much, but that was the basic voice that I had, and it was a normal voice to be writing in at that time, but I didn’t know this. I mean, I was not doing it on purpose. I tried writing from men’s points of view. I have a few stories from men’s point of view, from people of different color, different races, but basically my material was women’s lives, and I was a part of what was happening at that time, that’s all.

The poetry improved my prose, but the prose was equally good for my poetry. It loosened it up and made me more relevant to myself.

P&W: Were you concerned that because you wrote about women’s lives, your work might not be taken as seriously?

GP: I was very surprised by how well I was received. My experience was that men’s writing was interesting, and I really thought that for most people the lives of women would be very narrow in their appeal. But I couldn’t help the fact that I had not gone to war, and I had not done the male things. I had lived a woman’s life and that’s what I wrote about.

I’ll tell you an interesting thing, at least interesting to me. The poetry before I began to write stories, some of it, was very literary. I was a big reader. I was a big imitator, too. I sounded like I was a little bit British in my poetry. The fact that I came from the Bronx was irrelevant. When I began to write stories, I had the luck of having written poetry so that I had the language in my mouth. On the other hand, it was much looser since it was prose. That had a great effect on me when I continued to write poetry. The poetry improved my prose, but the prose was equally good for my poetry. It loosened it up and made me more relevant to myself.

P&W: Did you know when you first wrote about the character Faith who appears in so many of your stories that you would keep writing about her? And is there any significance to your choice of the name Faith?

GP: No. I didn’t know that I would keep writing about her. You wouldn’t believe this, but I like to make jokes, so I had this crazy idea that I would have a family in my stories with the names Faith, Hope, and Charlie. That was my dopey idea. It never worked, but she was stuck with the name Faith.

I want people to look at the world and see what's happening to it and take some action.

P&W: What led you to keep writing about her?

GP: Because she was a good worker. She did the job; she told the story. She seemed to have some brains. She had a sense of humor. She worked for me. Faith is not me; her life is entirely different from mine. My children lived with their father until they were twenty years old, and I was not a single mother, ever, not for five minutes. So Faith’s life is not mine, but she could have been one of my friends.

P&W: What advice do you give to younger writers?

GP: Have a low overhead. Don’t live with anybody who doesn’t support your work. Very important. And read a lot. Don’t be afraid to read or of being influenced by what you read. You’re more influenced by the voice of childhood than you are by some poet you’re reading. The last piece of advice is to keep a paper and pencil in your pocket at all times, especially if you’re a poet. But even if you’re a prose writer, you have to write things down when they come to you, or you lose them, and they’re gone forever. Of course, most of them are stupid, so it doesn’t matter. But in case they’re the thing that solves the problem for the story or the poem or whatever, you’d better keep a pencil and a paper in your pocket. I gave this big advice in a talk, and then about three hours later I told a student I really liked his work and asked how I could get in touch with him. He said he would give me his name and address. I looked in my pocket, and I didn’t have any pencil or paper.

P&W: I heard you speak years ago, and you said that you had some stories that had taken thirty years for you to find a way to tell. What was it that allowed you to finally tell the stories and why do some stories take so long?

GP: Well, that’s just me. I’m willing to let it go until it happens. I’m not going to push it too hard. Why should I? I mean, I don’t make a lot of money anyway, so if I finish this story I’ll be lucky if someone will publish it. Whether it’s a magazine that pays or a magazine that doesn’t pay will do me equally good. I don’t feel pushed, as far as that’s concerned. Most of the living I make is from giving readings. I never made a lot of money writing, anyway.

I struggle to be truthful to myself. I think that’s what literature is about; it’s the struggle for truth. It’s the struggle for what you don’t understand. So as long I don’t understand things I will be able to write, but once I understand everything, I won’t be able to write any more. There are things you want to understand. That is what writing is about. What kept me going writing stories is that all of a sudden I found the form I could use to try to understand in dialogue the people I’d been living with, the women I knew, and to try to make some history out of it somehow.

P&W: You have said that when you are a poet, you speak to the world, and when you are a story writer you get the world to speak to you. Could say more about this?

GP: In prose I do get the world to speak to me so I can understand it better, but it’s the same thing in poetry—speaking out to the world but also getting the world to speak to you. In writing both poetry and prose, you come from not understanding to trying to understand. In prose, you get these people to talk and figure things out for you, but in poetry you are on your own. So in poetry you’re really speaking more to yourself, addressing yourself and trying to understand something. But both voices, prose and poetry, are mysterious. You have to be a very good listener to be a writer. I talk a lot, but I’m a good listener with people. I’m interested in people, but I also like them. I’m very lucky in that because there are a lot of embittered people, grouchy people, writing books.

P&W: Does writing allow you to have moments of understanding?

GP: You have those experiences if you’re writing very often. You don’t know that you understand, but sometimes you have characters talking to each other and the purpose of their conversation is for you to understand something about them, which could happen without your knowing it. In a way, you keep writing to understand. You don’t do it, and then say, “Oh now, I understand, the story’s over.” You’re left pretty much still wondering, so there is that wonder and mystery.

Just looking out at the countryside here, I find it so amazing. If you look out that window, it’s so amazing, and the countryside is being murdered. People don’t understand what is being done to their countryside. In some parts of the world, they seem to understand it better than here. Here we don’t seem to get it that the fields are being wrecked by poisons and the air is close to the end of breathable. There is a great effort in America to stay happy and not worry and not understand and not do anything about it.

P&W: How do you see the future for this country?

GP: We have a big election coming up, and that’s on my mind. This administration is very dangerous, not just bad, but they’re really scary. I don’t remember anything like it. I didn’t like Reagan at all, and he did terrible things, but he was not like this administration.

I want people to look at the world and see what’s happening to it and take some action. This planet is so lovable. It is so various and so lovable, including all sorts of parts of the world that I’ve never seen, and I’ve seen more than most people. Just in what your eyes see, and how people live on the earth, it’s amazing, but it’s going to end if we don’t get our leaders to pay attention.

Human beings come from some little amoeba or paramecium. That’s what I learned in biology. Human beings come from several million years of development, which is quite wonderful. I have a lot of regard for what human beings have become. It took us a million years to learn how to speak to each other, and we did it. It took us another million years to work with each other, and we did it. I think the human race is remarkable. If it could only be nice to other animals, it would be even better. Meanwhile, it’s just like any other animal. It’s abusive and consumes the other species. That implies that we should all be vegetarian. Well in a sense, I am saying that. Until we live in a world where we stop abusing each other and the other creatures, we will not have reached our perfection.

No comments:

Post a Comment