|

| Ilustration by Eleonor Shakespeare |

The Very Quiet Foreign Girls poetry group

Kate Clanchy

Thursday 14 July 2016

It all came from Priya’s poem, and Priya’s poem came from – well, I had no idea. It was an unlikely thing to turn up in a pile of marking. Yet there it was, tucked between two ordinary effusions, typed in a silly, curly, childish font, a sonorous description, framed with exquisite irony, of everything she couldn’t remember about her “mother country”. This was the opening:

I don’t remember her

in the summer,

lagoon water sizzling,

the kingfisher leaping,

or even the sweet honey mangoes

they tell me I used to love.

I typed up a fresh copy of the poem in Times New Roman, removing a stray comma, marvelling at its shape. I printed out a copy and taped it to the staffroom tea urn, then made another, and took it across to the head of English, Miss B. She stuck it on her door, just above the handle, so that everyone entering or leaving her classroom had to read it.

Then I took it into my next class, Miss T’s year sevens. Our school, Oxford Spires Academy, despite its lofty, English name, meets every marker for deprivation and its students spoke more than 50 different languages. Miss T’s class, fairly typically, had students from 15 different mother countries. Some were born in Britain to parents from Bangladesh and Pakistan, some were migrants from eastern Europe or Brazil, a few were refugees from war zones: Iraq, Kurdistan, Afghanistan.

But none of them talked about it much. We are always, in this country, obliging refugees to tell their arrival stories: border officials, social workers, charity workers, housing officers all want to know, and the consequences of telling the wrong tale are dire. In our school, there is a code of silence. Teachers, on principle, accept each new arrival as simply a student equal to all others, and try to meet their needs as they appear. Students follow suit, speaking to each other in English, of English things, in mixed racial groups. This, mostly, is a good thing, but it does leave a layer of stories untold, and some festering, because very few people make it out of war zones by being exceptionally nice at all times. The more terrible the place they have fled, the more likely they are to have seen things that leave an awful, lingering sense of shame.

“I don’t remember,” our students say. “I came from my country when I was six but I don’t remember it. I don’t remember my language. No.”

Priya’s poem, though, was like a magic key. I read it to my class, then asked the students for a list of things they definitely didn’t remember, not at all, from their childhoods. In half an hour, we had 30 poems. Sana had written about her mother tongue: “How shameful, shameful, forgotten.” Ismail, who had never written a poem before, who rarely spoke, covered three pages with sensual remembrance, ending: “I don’t remember the fearless boy I used to be / no, I don’t remember my country, Bangladesh.” So many of them – and so good, so clear. I decided to create a poetry group.

Actually, I didn’t do it to be nice, or to help the kids “find a voice”. By that point, I had been working at the school for three years, partly funded by the charity First Story, and had done a lot of voice-finding already. Now, I thought it was time we won something. Specifically, the Foyle Young Poets of the Year award. The Poetry Society runs this competition each year, and the prize is a week’s writing course with all the other young winners.

I had judged the Foyle and run the course back in 2006, and seven years on, the Foyle young poets group I had taught were scything through Oxbridge, publishing poetry pamphlets with Faber, writing for the national press, and all the time networking frantically. By mixing together this group of exceptionally talented youngsters – many of them privileged but a few definitely not – that course had forcefully changed most of their lives. I wanted some of that for our students: not just the poetry, but the sense of entitlement, and, yes, the networking too. Just one child, I thought, could bring back a generous netful of cultural capital from a single trip.

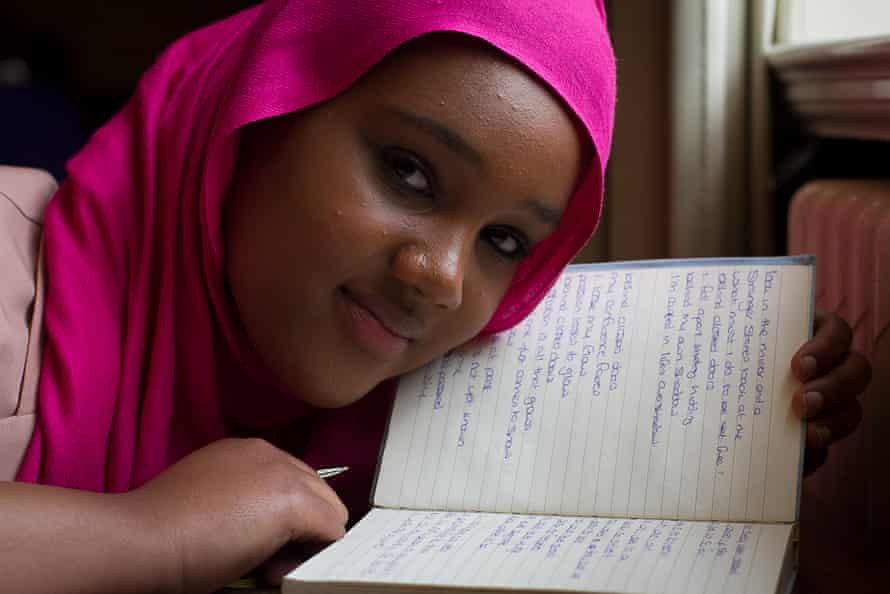

And now I believed that I could find a prize-winner among our migrant students. When I had started at the school, I had assumed, like some parts of the British press, that speaking English as an additional language was, for writing purposes, a negative – an area that would simply need extra work. Students such as Priya had changed my mind. I remembered teaching her the previous year, in a GCSE poetry anthology workshop, with Miss B’s lower English set. They were a particularly wildly mixed bunch, as lower sets always are, and Priya, doe-eyed in hijab, just arrived from a bankrupt religious school, was quiet as a shadow among them.

Miss B had sent me off with a small group to work on Carol Ann Duffy’s poem Originally (“the city, / the street, the house, the vacant rooms / where we didn’t live any more”), and we were remaking and breaking the line-breaks on a computer screen, finding out how they worked. In the cheerful noise, Priya was silent, and it was not till the end of the lesson that I leaned over and saw what she was working on:

There is that strange smell again, the tang of

the cars on the road screeching, not like

the laborious rickshaw in BangladeshLook ahead, jump, skip and hop. Hide the fact

you are alienated. Chew on the candy floss.

It melts in your mouth. Such foreign stuff!

She typed it in front of me, exactly like that, audacious line breaks, eccentric vocabulary, disturbing punctuation – the lot. The echo of Duffy was precise, but the original force of the poem even stronger. Priya was in the lower set because her critical skills were, at best, ragged, yet when it came to poetry it was as if she were listening, with extra ears, as much to the sounds of the words as their sense. I thought it might be to do with the loss of a language: Priya moved from Bangladesh when she was six. If that was the case, there might be more students like her in our school. In fact, we might have a wealth of them. Poets.

Now, I was going to make a group of them. Students tempered by loss – but not just that. I wanted those turned inward instead of outward, the quiet sort. Ones who read, of course, and preferably in two languages. And then something harder to describe: the ones who, whether they had arrived months or years previously, still seemed to live in two worlds and two languages. I also decided, just for once, to limit my group to girls. Several of the students I had in mind came from strict homes: it would help them speak freely if there were no boys around. And so it was that I asked the English department for some Very Quiet Foreign Girls.

My English colleagues are, to a woman, brilliant teachers. They also always get my jokes. Miss B said: “Oh yes, I have one for you. Kala only came last term, but she wrote something that was quite definitely a poem.” Miss W said: “Shakila won my competition – she’s great but not all that quiet.” Miss T, who is prone to melodrama, said: “Fatima! ‘So I left it there, my teddy-bear, its blank eyes staring’ … These lines are forever graven on my heart.” And Miss P said: “You can use my room.” That was particularly generous, as Miss P is very tidy, and I am not. Miss A raised an eyebrow dryly, and suggested: “Possibly find another name? You’ll have a problem getting all that on a T-shirt.”

Miss A is always right. The name we chose, officially, was the Other Countries Poetry Group and, for two terms, starting in Easter 2013, we met every Thursday lunchtime, in Miss P’s tidy room. It was quiet there, and when the bell rang, and the clamour of teenagers rushing to class rose around us like water, we had a special dispensation to stay on, in our sealed chamber, writing. Priya, of course, in the sixth form now, with floor-length dress, hijab, and braces on her teeth. She had brought her pretty younger sister Disha, and their slender, anxious friend Neelam. Then there was Fatima of the melancholy teddy bear, and Maryam, with the thick glasses and infinite naivety, both from India; Kala, Miss B’s silent, traumatised arrival from Sri Lanka; Shakila, recently from Afghanistan, tiny and fierce; and, younger than the others and white-blonde among all the black plaits and hijabs, Eszter, from Hungary.

We know that people learn new languages best by immersion – so why not poetry? Certainly, these girls seemed to learn form as they learned English: rapidly; and not word by word or brick by brick, but wholesale, structure by structure, arch by arch. Shakila in particular always seemed to the have the floor plan of a poem in her head and to need help only with filling in the blocks. She would call out to me for words, urgently, her black eyes snapping, slim fingers fluttering: “Thingies!”

“Miss! A thingy! A bird. You are in the desert. It is not an owl!”

“Vulture?”

“Yes! Spell, please!”

And her high-set, starched hijab would rustle as she wrote it down.

None of the girls were put off by difficulty. The stronger and stranger a poem, in fact, the more rhetorical and “poemy”, the more they liked it. So when we read Auden’s Look, Stranger – that most peculiar of poems – they reproduced its awed and awesome tone, its clotted sound, without seeming to think about it, and effortlessly translated its English cliff into their own landscapes. Eszter wrote about a Hungarian plain where the light was “riding its cloud horse”, and enjoined us to “remember it / the free and wild wind / like a gentle touch”. Shakila picked up on the verb form, and, after shouting for many “thingies”, created a poem about arrival at the airport, clutching “bags full of dictionaries”, all in the imperative.

And Priya, who was by now, it seemed fair to say, motoring, conjured up a magical Sylheti junglescape, where a Bengal tiger “obsolete as an emperor / breathes”. I saved that poem carefully, more sure than ever that she was certain to win. What would the Foyle young poets make of Priya, I wondered, looking at the winners’ ambitious CVs on the Poetry Society website, describing their hopes that the competition would set them on a literary course, find them an agent. Priya who had such a curious, interrupted education, who had taught herself so much on a mixture of the Qur’an and BBC2 documentaries; Priya who had no idea what a literary agent was, or an Oxbridge interview. I concluded she would do them good.

As the girls grew more confident, they became noisier, less pliable, more human, and talked to each other more. So much, in fact, that my goal of producing pure, medal-winning poetry sometimes seemed in danger of disappearing.

By May, Miss P’s room was filled with babble. Sometimes it was frustrated: Shakila on her furious quest for words; the low moans of Maryam suddenly giving up mid-poem, and insisting that each line she had written, each word, was in some indescribable way wrong. Mostly, though, it was cheerful. Tiny Fatima of the sad bear proved not to be melancholy at all, but impish – given to delivering runaway rants on the merits of Twilight. She wrote a long poem in an invented language – half-English, half-Urdu – and giggled at it until she fell off the seat and kicked up, under her long robe, outlandish high heels.

Disha and Neelam formed an alliance of satire, writing deliberate, dark counterpoints to Priya’s exquisite sun-filled laments. Both of them had had the experience of leaving Bangladesh as young children, and then returning as teenagers, only to be as alienated and terrified by their country’s poverty as they felt welcomed by its warmth. They could not say enough dark things about it, and at the same time, they could not love it enough, or leave the subject alone. One day, Disha wrote an utterly triumphant poem, a piece about Bangladesh that ran through a series of grand metaphors in grand language, discarding them all, and ended: “And so, my poem is my country / my home country / and my country is poor.” And she read it out, and looked over to her gifted, lyrical sister, and gave a tiny nod.

Even Priya could be garrulous, as very quiet people sometimes are. When Shakila was explaining to us that even though she was not a Sunni Muslim like most Afghans, but Shia, because she came from the Hazara minority, Priya, who was a Sunni, clasped her hands to her chest, and called out in almost physical distress: “Miss! When I found out about that, when I learned that that there were different kinds of Muslim – Shia, Sunni – I didn’t believe it. I said to my teacher in the mosque, this is not true, how can this be?”

Disha soothed her sister: “There is only one Qur’an,” she said. “There is only one Allah.”

“Miss!” said Priya. “Don’t laugh. When I was a little girl, I thought the television was true. I mean, the black and white. That was our television, Miss, black and white. And Miss! I thought the past was black and white, Miss – I thought England was black and white. And when I found it was colour … Miss! When I found out about Shia and Sunni, it was like that for me. When I realised I was wrong.”

Shakila leaned her hijab to Priya’s hijab, Shia to Sunni, and put her hands across the table. “You know,” she said, “in my country, they caught this terrorist, this bomber. They put him on television. He said he was doing it for the Taliban, but he didn’t know anything, he did not know … ” – and then she broke into Arabic, sharp and triumphant – “Asalaam alaykum.”

“What’s that?” asked Eszter.

“Peace be upon you,” said Disha. “It’s a salutation.”

Priya raised her head, her face brimming with feeling: “How can a Muslim hate another Muslim? It is terrible.”

And we all agreed.

We got good at agreeing. There was the day Maryam said, as I wondered aloud at her spelling: “Don’t laugh, Miss, but I didn’t write till I was 10. Didn’t read or write, not any language.” We all agreed, immediately, not to laugh. There was the time Fatima took us through her family’s visa problems, circuit by circuit of the Dickensian Circumlocution Office. We all agreed that the visa system was bust and unjust. How could you make a distinction between Kala and Shakila, who had left war zones, and Eszter and Fatima, who had left economic disasters, caste and class prejudice, corruption and hopelessness? But the day Shakila told us about the head, we didn’t know what to say.

By that time, it was Ramadan, and exam season, and also July, and also sports day. As a result, there were only three of us there: Priya pale from fasting; Shakila, also pale, also fasting, but she had run the 400m nonetheless; and me. We were looking at drafts, and Shakila handed me a sheet of A4. One side had a variation on a theme I had given the group the previous week, contrasting the morning adhan from the mosque in Afghanistan with the alarms in an English street. As they chatted, though, I looked at the writing on the other side, which was crossed out with a single line so the whole text was still visible and begging to be read. It was about a man sweating, and a scarf and a backpack and suspicious minds – what was this going to be, Shakila?

“Oh,” she said, “I was trying to write, you know, about terrorists.”

I didn’t know much about terrorists. I still didn’t know much about Shakila’s Hazara people, either, though I had looked them up on Wikipedia by then. I had learned they were the almond-eyed individuals who were the servants in The Kite Runner, that they spoke a form of Persian, and that they were persecuted by everybody: by the Pashtun majority in Afghanistan, by the Taliban in the Afghan-Pakistani borderlands, and by the Iranians, when they made it over the Afghanistan-Iran border. I had picked up a few more poetic details, too: they were a long-lived people who ate a lot of apricots, they greeted each other in verse, and they were obsessed with the mystic poet Rumi.

I asked Shakila: what sort of terrorist? She told me about going to the market in her dusty hometown. It was a hot day, but one young man among the shoppers was wearing layers of clothes, and sweating profusely, and Shakila, suddenly feeling that something was badly wrong, had seized her friend’s hand and run away through the streets. Many other people were running too, and they were all right to do so, because the young man had a bomb. He was a bomb. Shakila crouched behind a wall when the bomb went off. Boom.

The bell rang for a long time just then, and we flinched.

It was time to go. Priya picked up her bag. She said: “You need a frame, Shakila. For your poem. Miss. Give her a frame.”

A frame. Well, I had taught them this. Week by week, try this frame, try this shape, because we were writing excellent poems, not telling sad stories. Let’s write just in the imperative, or try the second person. Never, what is your trauma? Never, what happened to you? And anyway, I hadn’t the slightest idea how to frame a poem about a terrorist exploding.

Priya had gone to class. Shakila, though, was waiting, looking for a frame, looking for words.

“Miss! You know, bombs. They cut off bits of you, like your feet, your leg! And when the bomb goes off, Miss, those … thingies.”

“Body parts?” I suggested.

“Yes!” Shakila’s eyes brightened as they did when she sighted a really fine piece of vocabulary. “Body parts, they land in the town around.”

“Did that happen from the bomb in your poem?” I asked. “Did you see that?”

“Miss,” she said, “when I was behind the wall, a head came over. A whole head.”

“His head?” I asked. ‘The terrorist’s?’

“No,” she said. “A woman’s head. The bomb had killed her. Just a head.”

“Right.” I said, imagining a head. Shakila’s head, in fact, with its high cheekbones and intricate hijab, laid out on a plate like the head of John the Baptist, because who do I know of the Hazara people except my dear, my swift-running Shakila, with her ferocity and her bravery and her brains? Shakila was still waiting for some advice for her poem, and I reached deep for something to say.

“Sometimes,” I said, “poems like that take a long time to write.”

We didn’t win. None of my Quiet Girls’ poems actually won the Foyle award in September that year – not even Priya’s poem with the obsolete tiger, not even Eszter’s cloud-horse. But Esme did, another of our pupils, a lovely girl, who had been busy doing her GCSEs as my girls met. And she went on the Foyle course and brought back a lot of empowerment to the school, and personal joy, too. And in her footsteps, as I had hoped, in each year since, have followed more winners, in the Foyle and in many other competitions. More prizes than Eton and St Paul’s, glory enough to spread across the school. My vision of our school as a poetry hothouse, standing to verse as Kenya’s Great Rift Valley stands to long distance running, seems not as romantic as it did at first.

Sometimes, though, the same linguistic intuition that allowed my Quiet Girls to use music in their own poetry seems to preclude them writing critically about other people’s. Several of them can write exquisite, musical poetry while being completely unable to master the language to talk about it. Maryam, for example, not only struggled to get to an E grade in A-level English literature, but also got a D in AS-level creative writing in the very same year – and for the very same poem, that won her a place in the top 100 of the Foyle award. The piece in question began:

My poem is a jackfruit

the smell of it clings

and the insides feel

like the gooey ink

my brother puts

in his red car engine

Though what mark indeed would you give that? The impossibility of grading such ineffable mixtures of innocence and profundity, such magnificent protrusions of an entirely foreign accent, and conversely the difficulty of getting them to write A-grade prose without compromising their own voices, has become known in the English Department as the “jackfruit problem”.

Eszter, though, seems to have solved it: her critical writing is every bit as fine as her verse. As I write this, she is in a corner of the library, reading Jane Eyre. In all the recent updates and retellings of the Brontës, no one cast Jane or Lucy Snowe as an eastern European in England, because we always concentrate on Jane’s gender, not her class. But Eszter is experiencing education as Charlotte Brontë did: both as a precarious road out of dangerous poverty which requires ceaseless striving, and as the only possible means of self-expression. Eszter’s poems are as passionate as the paintings Jane shows Rochester, and also as accomplished, because she adores poetic form and will happily, indeed joyously, spend two hours adjusting three commas and a line break. She got stellar GCSEs. We hope she will apply to Cambridge next year.

Shakila has finished her poem. It took her three years, and it is a triumph: a highly wrought, rhetorical piece contrasting the Taliban’s empty words and promises of martyrdom with the physical reality of their deeds. The last stanza makes a play on the clouds of martyrdom and “the touch of the cheek of your dead, / cloud-soft, cold”. Audenesque compound nouns are no problem for Shakila, these days.

She and Disha now do everything together: study, fill in their Ucas forms, tutor children, make speeches at mock elections, sit arm in arm talking endlessly about politics, feminism and immigration. Last week, they came in to help me with new students from Syria and Kurdistan. “If you can write,” they told lads twice their weight, barely able to write their names in English, “you will find yourself.” We showed the students the little book we wrote in the Quiet Girls group, and read the poem by Shakila about the dictionaries, and one of the girls cried. Then Shakila stationed herself by a curious, sweet-faced Brazilian girl, helping her as she called out for words, and Disha stood over an abashed Kurdish boy reassuring him, word by word, that yes, it was OK to write that. At the end of the hour, Disha’s pupil stood: I have never written a poem, he said. But now I have. And he read.

The students love each other’s poems, and gain much from them. Shakila’s early poem spoke directly to the new migrants because its voice is so direct, and its simple but very solid, structure, drawn from her own background in oral poetry, gave their thoughts a shape. Later, when they are more confident and more impatient, I shall show the new students Disha’s poem, the one where all the metaphors don’t work, and the country is poor, and they can borrow that form to express their own divisions.

Best of all for teaching purposes is My Mother Country by Priya, which started the whole thing. I must have read this poem to a dozen classes now, and asked 200 children to write down what they don’t remember about their native land:

her comforting garment,

her saps of date trees,

providing the meagre earrings,

for those farmers

out there

in the gulf

under the calidity of the sun.

Each time I read it is like casting a spell: out come memories of lost grandparents, poppy cakes, paprika pots, chickens, mountains, languages.

That is better than prizes, really. Priya, who is sometimes almost irritatingly spiritual, would certainly say so. But I still carry a resentment that her poem – that none of her poems – ever won one of those national competitions, that the sweet soulful kids from Westminster and St Paul’s who did – the kids who will, most probably, run our future publishing houses – were never confronted by Priya’s experience.

It wasn’t for want of trying. I sent My Mother Country out eight times. Perhaps it sounds too effortless. Perhaps it is too short. Perhaps people don’t believe a 17-year-old wrote it – it has an ageless quality. Or perhaps we have not tuned in to this voice yet, the voice of our new England, an English inflected with all the accents of the world, with the mass migration of the early years of the 21st century, the voices of the Very Quiet Foreign Girls.

In our school we value this poem especially, and have blown it up 6ft-high, framed it and hung in the English corridor, next to Miss P’s room: a life-sized permanent reminder of the Very Quiet Foreign Girls. When we showed the result to Priya she gazed at it for a long while, pleased, then said: “Look, all the ‘o’s.” The poem is indeed studded with them:

or the mosquitoes,

droning in the monsoon,

or the tipa tapa of the rain,

on the tin roofs,

dripping on the window,

I think.

Blown up to that size, the “o”s look like portholes, or lifebelts, or pools, and now each year new generations of students gaze through them, or hang on to them, or dive into them, and start to write about what they can’t remember.

Main illustration by Eleanor Shakespeare.

Some names have been changed.

- Illustration by Eleanor Shakespeare

No comments:

Post a Comment