Not in Vain

If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain:

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin

Unto his nest again,

I shall not live in vain.

— Emily Dickinson

If I can stop one heart from breaking,

I shall not live in vain:

If I can ease one life the aching,

Or cool one pain,

Or help one fainting robin

Unto his nest again,

I shall not live in vain.

— Emily Dickinson

|

| Emily Dickinson |

On March 5, 1853, while her family ate breakfast, Emily Dickinson addressed four envelopes to Susan Gilbert, a woman with whom she seemed to be in love. The envelopes were empty. Though Emily had already written Sue several letters—and would, over the decades to come, write her hundreds more—these particular envelopes would not carry her words. Instead, Emily left the envelopes for her brother, Austin, who wanted to write to Sue in secret, and who happened to be in love with her himself.

Austin and Sue may already have been engaged at this point, though they wouldn’t announce it until Thanksgiving—and wouldn’t marry until 1856. They would eventually have three children. On the day that Emily addressed the envelopes for her brother, she and Sue were just twenty-two years old; Austin, on his way to law school, was a month from turning twenty-four. And yet, in a separate letter to Sue, Dickinson claimed to be imagining a future well beyond their earthly years:

Dear Susie, I dont forget you a moment of the hour, and when my work is finished, and I have got the tea, I slip thro’ the little entry, and out at the front door, and stand and watch the west, and remember all of mine—yes, Susie—the golden west, and the great, silent Eternity, forever folded there, and bye and bye it will open it’s everlasting arms, and gather us all—all.

Neither the distance between them nor their time apart seems commensurate with yearning on such a grand scale: Sue wasn’t across the sea, just in New Hampshire for a month. Perhaps Dickinson was responding, instead, to a separation on the horizon: the one augured, paradoxically, by the growing intimacy between her brother and her friend. But why, then, would Emily address those envelopes for her brother, and facilitate the courtship that would put Sue out of reach?

Consider the fantasy described by Dickinson at the end of the letter—one of more than thirteen hundred in “The Letters of Emily Dickinson” (Harvard), a new, definitive edition that collects, reorders, and freshly annotates every surviving letter that Dickinson sent (or drafted) to someone else, along with the handful of surviving messages that she received. What Dickinson wants is not simply to have Sue to herself, here and now. Her desire extends past any single object or fixed span of time; she wants nothing less than “Eternity,” a golden state that is presently silent and hidden, but one that will nevertheless, inevitably, unfold its arms in welcome. Those arms, in Dickinson’s fantasy, will gather together not only Emily and Sue but also Austin, along with everyone else who matters to her: “us all—all.”

For Dickinson, writing letters offered a way of making a life out of this fantasy; this is why the genre so appealed to her. When, for instance, she addressed the envelopes for her brother to send to Sue, she was of course helping the couple by hastening their courtship, but she was doing something else, too. She was insinuating herself into its private scenes. Letters untether words from bodies; they loosen and redraw the bonds of time and space, and for that matter of sexuality, marriage, and blood relation. A week later, she wrote to Sue again, describing the pleasure she had taken in arranging her friend’s correspondence with her brother: “So Susie, I set the trap and catch the little mouse, and love to catch him dearly, for I think of you and Austin, and know it pleases you to have my tiny services.”

One gets the sense that Dickinson’s desires for these kinds of tangled intimacy frequently exceeded her correspondents’ interest in satisfying them. Almost all of the letters that Dickinson received were destroyed after her death, but her own surviving letters frequently complain about epistolary neglect. To Austin, in this same stretch, she writes, “I have not heard from Sue again, tho’ I’ve written her three times.” And yet such frustration did little to curb her desire. On March 23, 1853, Austin and Sue met in the parlor of the Revere Hotel in Boston. The next day, Emily wrote to her brother: “I did ‘drop in at the Revere’ a great many times yesterday. I hope you have been made happy. If so I am satisfied. I shall know when you get home.” Hard to imagine that Austin and Sue were thinking of Emily as they sat together in the Revere. But she was thinking of them.

***

Two tendencies animate Dickinson’s letters, two ways of imagining what writing might do. On the one hand, and especially as she entered adulthood, writing could feel like a mode of retreat from the world. This way of imagining Dickinson—as an eccentric recluse—became part of her mythology even in life, and it was an image that she played no small part in promoting. In 1869, when Dickinson was thirty-eight years old, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, the man who (through the mail) had become her poetic mentor, asked her if they could meet: “if I could once see you & know that you are real, I might fare better.” Dickinson’s response suggested that she preferred a state of slight unreality: “A Letter always feels to me like immortality because it is the mind alone without corporeal friend.”

Dickinson did eventually consent to see Higginson in person. After their second (and final) meeting, he wrote to his sister, “I saw my eccentric poetess Miss Emily Dickinson who never goes outside her father’s grounds & sees only me & a few others. She says, ‘there is always one thing to be grateful for—that one is one’s self & not somebody else.’ ” Never going outside your father’s grounds may be a way to insure that you do not become somebody else. Dickinson’s writing, in this way of thinking, created a simulated world that took the place of the real one. She once responded to a social invitation from Sue by writing simply, “We meet no Stranger but Ourself.” Thomas H. Johnson, the editor of the standard 1958 edition of Dickinson’s letters which this new volume supersedes, took this view to its extreme when, in his introduction, he stated, as fact: “she did not live in history and held no view of it.”

The nearly seven decades of scholarship that have followed Johnson’s pronouncement of Dickinson’s reclusiveness—scholarship to which Cristanne Miller and Domhnall Mitchell, the new volume’s editors, have contributed and from which they adroitly draw—have revealed it to be a crude caricature, one that says as much about men’s fantasies about women (and about poetry readers’ fantasies about poets) as it does about the actual person who wrote those thousand-odd letters. What that scholarship helps us to see is the countervailing tendency behind Dickinson’s epistolary practice: again and again, she set her thoughts to paper and then sent those sheets of paper out into the world, where they found the hands of someone else. Writing letters could therefore be for Dickinson not only a withdrawal from the world but also a way of extending herself into many worlds, all at once.

She took great delight in imagining the varied routes that her words would take, the worlds they’d help her inhabit. In 1852, when Sue was teaching in Baltimore, Dickinson lamented that she could not close the distance between them, that she could not make their diffuse intimacy into something compact, like a poem. And yet that lamentation, as Dickinson offered it, turned into its own form of consolation:

I mourn this morning, Susie, that I have no sweet sunset to gild a page for you, nor any bay so blue—not even a little chamber way up in the sky, as your’s is, to give me thoughts of heaven, which I would give to you. You know how I must write you, down, down, in the terrestrial; no sunset here, no stars; not even a bit of twilight which I may poetize, and send you! Yet Susie, there will be romance in the letter’s ride to you—think of the hills and dales, and the rivers it will pass over, and the drivers and conductors who will hurry it on to you; and wont that make a poem such as ne’er can be written?

The scholar Virginia Jackson has taken this passage as emblematic of Dickinson’s persistent attention to the “material circumstances of writing,” which produce their own kind of intimacy. The predicament faced by every letter writer is that they cannot, at the time of their writing, share a world with their reader. But, when Dickinson sets her world to paper, and mails it to Baltimore, the page itself becomes a shared object, a bit of the world that writer and reader will have had in common, though separated in time. Because the letter is itself a material object, because that object begins in Emily’s hands and ends in Sue’s, the very distance between them becomes an image of their intimacy, now manifested in the postal route that gets the sheet of paper from writer to reader.

“Mother is frying Doughnuts,” Dickinson wrote, at around this time, in a postscript to her brother, who was teaching in Boston. “I will give you a little platefull to have warm for your tea! Imaginary ones—how I’d love to send you real ones.” She can’t send Austin the doughnuts and expect them to arrive warm, but in their place she sends folded paper that bears ink from her pen—with the expectation that, when Austin unfolds it and reads, he will have been connected in a very literal way to the domestic scene from which he had been absent. Epistolary writing offered Dickinson a way to draw tenderness from separation, to make distance an image of love. In 1866, a decade after Sue and Austin were married, Dickinson sent her sister-in-law a folded sheet of paper that contained only these pencilled words:

Distance—is notthe Realm of FoxNor by Relay ofBirdAbated—Distance isUntil thyself, Beloved.Emily—

***

That sheet of paper did not have far to go. When Sue and Austin married, they moved into the Evergreens, a house on the lot adjacent to the Dickinson family home, where Emily still lived with her mother, father, and sister, Lavinia. Dickinson sent Sue more letters than any other correspondent—this edition contains nearly three hundred to her alone—and yet, for most of that correspondence, Sue was just next door. Out of view but close at hand, Sue became an ideal recipient for the poems that Dickinson, on the verge of her great outburst of creativity, increasingly began to write:

One Sister have I in our house,And one, a hedge away.There’s only one recorded,But both belong to me.

Dickinson sent the poem that begins with this stanza to the Evergreens on the occasion of Sue’s twenty-eighth birthday. The two women, born just nine days apart, had not become close friends until 1850, when they would both have been nineteen, but the poem maintains its own logic. To claim Sue as “sister,” to feel in the present the intensity of that affection, was to bring a notionally shared childhood within reach:

Today is far from Childhood,But up and down the hillsI held her hand the tighter,Which shortened all the miles—

In her letters, Dickinson often refers to childhood nostalgically. To Austin, she writes, “I wish we were children now. I wish we were always children, how to grow up I dont know!” At other times, though, “childhood” names a world to come. Writing to Higginson, in a letter she drafts in 1870, Dickinson refers to “immortality” as “the larger Haunted House it seems, of maturer Childhood—distant, an alarm—entered intimate at last as a neighbor’s Cottage—”

***

Dickinson’s father died four years later, when she was forty-three. The event arrives with a terrible poignancy in the “Letters.” The only surviving note from Dickinson to her father was written just before his death—and is blank:

Dear Father—

Emily—

Between the salutation and the signature, the editors point out, are two pinholes. They suggest that the note held an object—likely a flower—which is now gone. The next letter in the volume is from Dickinson to her two younger cousins, Louisa and Frances Norcross, and tells the story of the Dickinson children receiving word that their father had died:

Father does not live with us now—he lives in a new house. Though it was built in an hour it is better than this. He hasn’t any garden because he moved after gardens were made, so we take him the best flowers, and if we only knew he knew, perhaps we could stop crying.

Dickinson did not attend her father’s burial, and, according to the “Letters,” she never visited his grave, though her siblings did. A friend of hers, Elizabeth Holland, picked a sprig of clover from the grave and gave it to Emily, who pressed it between the pages of her Bible. A letter may indeed, as Dickinson wrote to Higginson, feel like immortality, but there is something profoundly elegiac in this circuit of exchange: the flower now missing from the note to her father, the brute fact that he cannot receive the flowers his children now bring him, the flower preserved from the grave never visited. Letters circulate such traces of organic matter, even as they implicitly bemoan their insufficiencies.

***

Again and again, one feels the pathos of this collection. The editors have performed a monumental act of labor—consulting historical weather reports, diaries, and newspaper archives to reconstruct chronology; painstakingly restoring words erased by later hands—but inevitably there are things we just cannot know with any certainty about the person who produced these texts.

Nowhere is that pathos more acute than in the love letters that suddenly appear near the end of Dickinson’s life. Addressed to Otis Lord, a Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court judge whom Dickinson described as “my Father’s closest friend,” the twenty letters survive only as drafts. Lord was a widower, eighteen years Emily’s senior. The romance between them began sometime around 1880; Dickinson would have been nearly fifty. They agreed to write to each other every Sunday. “Tuesday is a deeply depressed Day,” Dickinson complained in a draft to Lord; “it is not far enough from your dear note for the embryo of another to form, and yet what flights of Distance.”

According to Alfred Habegger, one of Dickinson’s biographers, Lord asked her to marry him late in 1882. Here, again, it’s impossible to know the details of what happened between the two. But, throughout Dickinson’s drafts to Lord, we have evidence of that same twinned impulse that guided her earlier letters to Sue. On the one hand, amorous withdrawal: “Dont you know you are happiest while I withhold and not confer—dont you know that ‘No’ is the wildest word we consign to Language?” On the other, an oddly chaste kind of eros: “It is strange that I miss you at night so much when I was never with you.” In the same breath, Dickinson seems to voice regret about having missed a life with Lord (“Oh, had I found it sooner!”) and an otherworldly sense that, in the face of such strong feeling, chronology is beside the point (“Yet Tenderness has not a Date—it comes—and overwhelms”). Lord died in 1884; Dickinson two years later, at the age of fifty-five. At the poet’s funeral, her sister, Lavinia, laid two flowers by her hand, “to take to Judge Lord.”

Three decades earlier, while Emily was assisting in her brother’s courtship, she wrote to Sue, “There are lives, sometimes, Susie—Bless God that we catch faint glimpses of his brighter Paradise from occasional Heavens here!” Her own life was lived in that terrestrial “here,” and also in her writing. What glimpses of paradise it gives. Very near the end of the letters collected in this volume, there is a note marked by the editors as “unsent.” Its recipient is unknown: “Were Departure Separation, there would be neither Nature nor Art, for there would be no World—”. The slip of paper has been folded once and is signed “Emily—”. The woman who signed her name there has gone away. Her note is not addressed to us. And yet, in having found our hands, it tells us that we share a world with its author.

***

Kamran Javadizadeh is an associate professor of English at Villanova University and the author of the forthcoming book “Institutionalized

Take this city

bite it like an apple

if they kick you out

don’t be sad

cities are all hell.

Walk to the fields

strip naked

bathe in the sun

make a tent of your clothes

to shade a springing flower

don’t walk away

when the hyenas draw near;

everything around you is a predator.

Just remember

you are truly free.

* An imaginary letter written to us by an escaped prisoner, or another free man, and left this morning beneath an olive tree overlooking Marj ibn Amir.

Translator’s Note: The following poem by Palestinian poet Carol Sansour was slated to appear in Kontinentaldrift: Das Arabische Europa(Continental drift: the Arab Europe, 2023) but was among ten poems abruptly removed by German publishers Haus für Poesie. Edited by Ghayath Almadhoun and Sylvia Geist, the ground-breaking anthology features work by thirty-one poets writing in Arabic who are based in Europe. In the introduction to the anthology, Almadhoun writes: “bitterness is virtually everywhere in the texts [in the anthology]; you can touch it and yet it slips away like water through fingers.” In this poem, bitterness is mingled with a sense of wonder inspired by the spectacular escape of six Palestinian prisoners who dug their way out of jail using spoons in 2021. In another poem which was included in the anthology, Sansour writes: “In the East there is no home without war.”

Lost and Found: Children’s Poet Kaneko Misuzu

March 16, 2021

Bird, Bell, and I

Even if I spread my arms wide,

I can’t fly through the sky,

but still the little bird who flies

can’t run on the ground as fast as I.Even if I shake my body about

no pretty sound comes out,

but still, the tinkling bell

doesn’t know as many songs as I.Bird, bell, and I,

We’re all different, and that’s just fine.(Translated by David Jacobson, Sally Ito, and Tsuboi Michiko)

This is one of Kaneko Misuzu’s best-known works. The poem conveys a message of tolerance and understanding, one that finds value in diverse ways of being: Everyone is different, but everyone has their own strengths. You are what you are. It’s all right to be yourself. All life on earth, including human beings, has its unique strengths and its own role to play. These differences make all lifeforms precious and unique. Everyone is perfect in their own way: the perfect version of their own unique self.

It is a vision of the world that is far removed from an egotistical, human-centered understanding.

My favorite part of the poem is the first line of the final stanza. The title of the poem in Japanese is “Watashi to kotori to suzu to” (Me, the little bird, and the bell) but the line in the poem itself reverses this order to refer to “suzu to kotori to, sorekara watashi” “the bell, the little bird, and me.” Not “me and you,” but “you and I”—this choice expresses an openness and acceptance of others, delighting in the differences that make each of us precious and unique. We’re all different, but we all have our special qualities.

Another important aspect of the poem is the way in which it focuses on the things we can’t do, and all the things we do not know: the speaker can’t fly like a bird, but then the bird can’t run as fast as she can along the ground. We are all champions within our own areas of expertise.

When we come into the world, we are helpless and ignorant creatures who can do nothing for ourselves. As our knowledge and abilities increase, we often start to discriminate between those who can do things and others who cannot.

Misuzu focuses first on the things that we can’t do, and only then reminds us of the things we can do and the types of knowledge we do possess. The poem reminds us that we all have our own stories, our own histories, our own accomplishments and experiences. We are all precious beings with our own unique gifts.

Stars and Dandelions

Deep in the blue sky,

like pebbles at the bottom of the sea

lie the stars unseen in daylight

until night comes.

You can’t see them, but they are there

Unseen things are still there.The withered, seedless dandelions

hidden in the cracks of the roof tile

wait silently for spring,

their strong roots unseen.

You can’t see them, but they are there.

Unseen things are still there.(Translated by David Jacobson, Sally Ito, and Tsuboi Michiko.)

Here, Misuzu reminds us of all the little things that lie beyond our sight in the world, encouraging us to break away from our tendency to focus only on the things we can see. There are hints here of the same sensibility we saw in “The Big Catch,” where she writes of the invisible sadness of the sardines beneath the waves, mourning their friends and relatives who have been caught in the fishermen’s nets.

As well as the visible things around us, our surroundings are also filled with invisible air. It is thanks to this air that we are alive. There are many things we can’t see: not because they don’t exist, but because—just like the stars during the daytime or the dandelions hidden high up in the rooftops—we forget about them or fail to notice them because of a lack of imagination and an inability to go beyond the surface and think more deeply about things.

The verse brings to our attention the things we had failed to notice before, spurring us to take stock and look properly at all these things that help us make us who we are.

Blanket of Snow

Snow on top,

It must feel cold,

The chill moon shining down.Snow on the bottom,

It must feel heavy,

Hundreds of people on you.Snow in the middle,

It must feel lonely,

No earth or sky to look at.(Translated by D. P. Dutcher)

Reading this poem about a piled-up blanket of snow, I am moved by the way in which the poet does not see snow simply as an undifferentiated mass, but instead takes careful note of the three different layers of snow on top, bottom, and middle. Although other people might have come up with the conceit of the snow on the top and on the bottom, probably not many people had ever thought about the snow in the middle before.

Whenever I read this poem, I am reminded of the words of a village head I met once in Hokkaidō, where I had traveled to see the drift ice. He welcomed us to his village and then recited lines from the poem by heart.

“All my life, I’ve seen so much snow,” he told us. “And now I’m in my seventies. But until this year I had never once thought about the snow in the middle. I feel ashamed of myself for never having considered that which is truly important in all those years.” And he started to weep again.

His response drove me to reflect within myself about Misuzu’s children’s songs. I felt a voice within my heart asking insistently: like that elderly village head, had I too not lived my life without ever looking at what really matters in life?

Kaneko Misuzu’s poems pose the same probing question of anyone who reads them: “And what about you?”

Kaneko Misuzu (real name Teru) was born in 1903 in the fishing port of Senzaki on the Japan Sea coast of Yamaguchi Prefecture. During a brief career as a writer, she became one of Japan’s most accomplished writers of poetry and songs for children. She died in 1930 at the age of just 26. After her death, her work fell into neglect for decades. The writer Yazaki Setsuo searched for traces of Misuzu for decades until finally discovering a manuscript containing 512 of her poems, which was published as a new edition of her complete works in in 1984.

(Originally written in Japanese. English poems “Bird, Bell and I” and “Stars and Dandelions” are from the book Are You an Echo? The Lost Poetry of Misuzu Kaneko, translated by David Jacobson, Sally Ito, and Tsuboi Michiko. “Blanket of Snow” is from the book Something Nice translated by D. P. Dutcher. Illustrations © Moeko.)

NIPPON

Matsuo Bashō was around 45 in May 1689 when he began the five-month journey across Japan that inspired the most famous of his travel journals: Oku no hosomichi (trans. by Steven D. Carter as The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands). From his home in Fukagawa, Edo (now Tokyo), he traveled north to Hiraizumi in what is now Iwate Prefecture, then west and down the Sea of Japan coast, before finishing his trek at Ōgaki in what is now Gifu Prefecture.

For most of the trip, as far as Yamanaka Hot Springs, Bashō was accompanied by his disciple, known in the text as Kawai Sora (although the scholar Muramatsu Tomotsugu has shown his real name was Kasai Sora). He also traveled with the haiku poet Tachibana Hokushi from Kanazawa to just before Fukui. As well as visiting historic spots known for poetic associations or past battles, he wanted to meet poets, create linked verse together, and convey his version of haikai, the light, humorous literary genre that he played such a great part in shaping. Another motive was likely to have been that it was the five hundredth year since the death of Saigyō, a literary forebear Bashō much admired, who had similarly journeyed to Hiraizumi. There are frequent moments in the text where one can sense Bashō is deeply conscious of the earlier writer. He is believed to have edited the work into its final form from 1692, three years after the journey, to 1694, the year of his death.

From Sora’s diary, which gives an account of what took place on the expedition, it is apparent that The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands contains much description that is different from what actually happened. While Bashō based his literary travel journal on the real journey, he incorporated many of his own original ideas. One might call it almost a work of fiction, and in this sense, it holds a distinctive place among Japan’s classic travel literature. Broadly, it makes use of the following three approaches.

The journey takes place from the end of spring to the end of autumn, and the work is highly focused on the seasonal transitions and annual observances during this time. The narrator is also frequently moved by realizing the passage of time when viewing items, sites, or customs connected to the distant past.

There is a form of nō called the mugen-nō (dream play) in which the shite or main character is a ghost appearing in the dream of the waki or supporting character. There are parts in The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands where one senses the influence of dialogues with people no longer of this world.

While the work has a first-person narrator, it is not stated that this is Bashō himself. Bashō molds the narrator as an admirer of Saigyō, who follows the earlier poet’s actions.

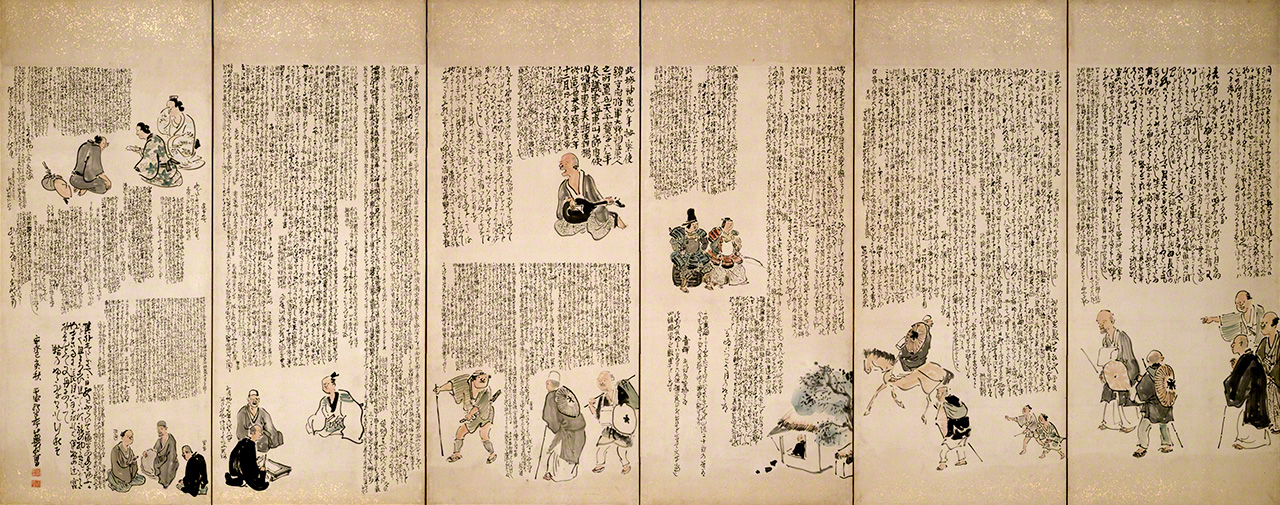

Yosa Buson, Oku no hosomichi-zu byōbu, 1779. Buson created this folding screen with the text of The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands and pictures of its various episodes out of his esteem for Bashō. (Courtesy Yamagata Museum of Art, Hasegawa Collection)

I will begin by considering the work’s opening.

The months and days are travelers through the ages, and so too are the years that come and go. For boatmen who spend their lives on the water and drivers who grow old leading their horses, every day is journeying, and journeying is their home. Many of the ancients died on the road, and I too, for some years, have been drawn to follow the wind like a wisp of cloud, unable to contain my wanderlust. I roamed along the coast . . .

There is a clear focus on time, as a concept likened to travelers, and more specifically as the traveling companion of the narrator. This “I” will go on to make note of the beginning of summer and autumn, as well as specific calendar festivals, including Tango no Sekku, Tanabata, Obon, and the night of the mid-autumn moon. He also views heirlooms left by Minamoto no Yoshitsune and his servant Benkei—who were driven north to Hiraizumi by the former’s half-brother Yoritomo, the founder of the Kamakura shōgunate—and goes to historic spots like the Konjikidō hall at the temple Chūsonji in Hiraizumi. Such connections to the past move him to tears.

Next, I would like to look at the section in Takadachi, Hiraizumi, the battlefield where Yoshitsune and his followers were defeated. Incidentally, Saigyō journeyed to Hiraizumi while Yoshitsune was sheltering there.

Yoshitsune’s retainers made their stand here and won glory in combat, but the moment passed, and their glory turned to grass. “The state in ruins, mountains and rivers remain. Spring green grows on the fortress.” Setting down my hat, I forgot the passing of time, and wept.

夏草や兵どもが夢の跡

Natsu kusa ya / tsuwamono-domo ga / yume no ato

Summer grasses,

all that remain of

warrior dreams卯の花に兼房みゆる白毛かな 曽良

Unohana ni / Kanefusa miyuru / shiraga kana (Sora)

In the deutzia flowers,

I see Kanefusa’s

white hair

(poem by Sora)

This section shows a strong influence from the mugen-nō. It is written so that it could be read that the narrator forgets the passing of time in lamenting the past battle where Yoshitsune and his retainers were defeated. In that time, the warriors appear in his dream to recount the events of the battle to him, and when he wakes, all that remains are the summer grasses.

The passage also suggest that it was in a dream that Sora saw the white hair of the warrior Kanefusa from the losing army. Sora’s real-life diary does not include the haiku, which seems to have actually been Bashō’s later invention. In nō terms, if the narrator is the waki (supporting character), Sora is the wakitsure (supporting character’s companion), and both offer poems to those who fell in battle.

The following passage, describing Bashō’s arrival in what is now Fukui Prefecture, is a good example of how the narrator is presented as a follower of Saigyō.

We crossed the border into Echizen, and over the Yoshizaki Inlet by boat, visiting the Shiogoshi Pines.

終宵嵐に波を運ばせて

月を垂れたる汐越の松 西行

Yo mo sugara / arashi ni nami o / hakobasete /

tsuki o taretaru / Shiogoshi no matsu (Saigyō)

All night

battered by

stormy waves,

moonlight in the falling drops—

Shiogoshi Pines

(poem by Saigyō)This one poem conveys the place’s beauties in all its forms. To add anything would be like putting a sixth finger on a hand.

The poem here is, in fact, the work of another writer called Rennyo, and the idea that Saigyō wrote it is Bashō’s invention. Rennyo was a major Buddhist figure, and the moon symbolizes enlightenment. Thus, Bashō uses this poem in The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands to show, through the moon, Saigyō’s accomplishment of Buddhist training, as well as the narrator’s desire to praise him.

Various versions of the text were produced before Bashō’s death in 1694. His handwritten manuscript is known as the Nakao version after its 1996 discoverer. The Sora version—so called as it was passed down through Sora’s family—is a faithful copy, which was further revised and polished. The Nishimura version, named after its owner, is a copy of the Sora version made by the calligrapher Kashiwagi Soryū at Bashō’s request, while another copy made by him is called the Kakimori version, as it is owned by Kakimori Bunko.

All of these are handwritten. Bashō apparently showed no intention to publish The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands. What does it mean that he only left handwritten manuscripts? One reason may be the comparative value of rarity, which would be lost through printing many copies. There are many ways to interpret the situation, but I would suggest that Bashō saw the text as a work in progress, which he intended to further refine.

In the year of his death, Bashō took the Nishimura version back to his hometown in Iga Province (now Mie Prefecture), where he presented it to his older brother Matsuo Hanzaemon. It then passed to Bashō’s disciple Mukai Kyorai, and this version was published by Izutsuya in Kyoto in 1702. This was the basis for numerous later reprintings. It was long considered the only version, until various manuscripts were discovered in the twentieth century. The original Nishimura version was found in 1943, the Sora version in 1951, the Kakimori version in 1959, and the Nakao version in 1996. It was in 1943 that Sora’s diary emerged to give an alternate version of events. These discoveries have given fresh impetus to studies of Bashō’s classic.

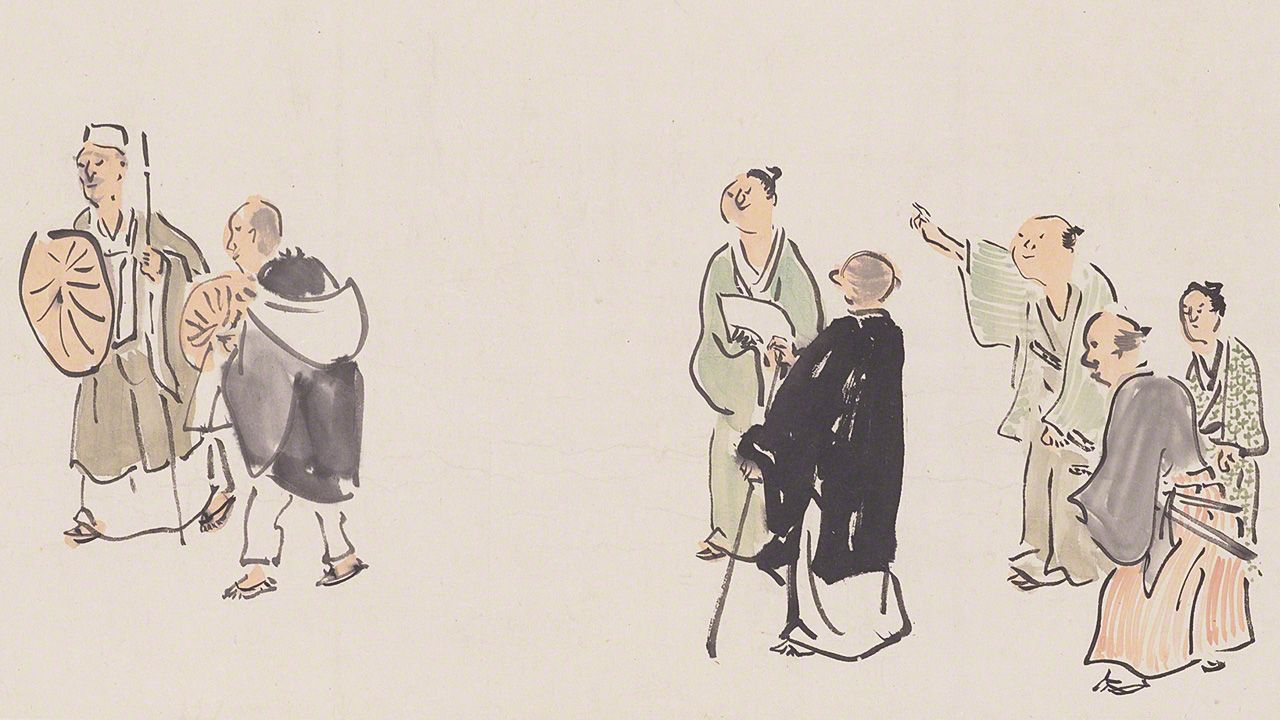

(Originally published in Japanese on April 20, 2022. Banner image: Yosa Buson, Shihon tansai oku no hosomichi-zu [Picture from The Narrow Road Through the Hinterlands in Light Colors on Paper], 1779. Buson’s illustration shows Bashō and Sora setting off from Senju in today’s Adachi, Tokyo. Courtesy Hankyū Culture Foundation/Itsuō Museum.)

NIPPON

29 JULY 2020

The early-twentieth-century poet Yosano Akiko earned herself a place in Japan’s literary history. She also left behind a series of essays on the influenza pandemic that hit Japan hard in the years following World War I. What do they have to say to those of us living through today’s COVID-19 pandemic?

Yosano Akiko (1878–1942), the foremost female poet of twentieth-century Japan, wrote the poem “From an Old Nest” in 1915, but it could be an ode to these past sequestered months of ours.

“From an Old Nest”

Skyward storms, don’t ask me along

while you wander aimlessly hither and yon,

bending the mountains, ravishing the fields—Earthbound as I am, I could not bear it.

Wild flowers’ fragrance, don’t murmur to me.

If I were to become a flower’s scent

I would perfume an instant of time—And then vanish forevermore.

Birds in the trees, don’t sing to me.

Born with wings, you fly

from branch to branch,singing your way from flower to flower.

All things, all, turn yourselves away from me—

Over and over in my small voice,

repeating the whisper that never changes,I rest in the nest of first love.

(Yomiuri Shimbun, July 25, 1915; Maigoromo, 1916)

The ending is a surprise—the “old” nest of the title becomes the place of “first” love. Shouldn’t it be a new nest? But that is the point. Love has survived the years. Even in the most difficult times of her marriage, Akiko believed that. And what of the unchanging whisper? Is it speaking words of love or something else? Such mysteries aside, the poem reminds us that there can be, after all, reasons to like staying at home. Sometimes there are things there that you can find nowhere else.

The romantic, visionary persona of this poem is one side of Yosano Akiko. But she was also a mother—giving birth to 13 children, 11 of whom survived to adulthood, products of a long and loving marriage—and an amazingly prolific social critic, best remembered now for the Motherhood Protection Debate (1918–19) that she carried on in the pages of widely read magazines with her sister feminists Hiratsuka Raichō, Yamakawa Kikue, and Yamada Waka. During the same period and then again a few years afterward, Akiko published five opinion pieces related to the influenza pandemic of 1918–21. Her platform was the Yokohama Bōeki Shimbun, one of the leading progressive newspapers of the day.

Worldwide, the influenza pandemic infected 500 million people and killed from 17 million to 50 million, possibly as many as 100 million. More than 20 million people died in World War I, so the pandemic was as deadly, or more so, than the war. In Japan, as elsewhere, exact numbers are impossible to come by, but the best estimate is that about 42% of Japanese were infected and about 400,000 died. Globally, the pandemic had three waves, the dates slightest different depending on the country. In Japan, the first wave was from August 1918 to July 1919, the second (and most virulent) from October 1919 to July 1920, and the third from August 1920 to July 1921.

In November 1918, at the peak of the first wave, Akiko published “Kanbō no toko kara” (From an Influenza Sickbed), her thoughts while she and 10 other members of her 13-person family were ill with influenza. The first half was devoted to the epidemic. Progress in global transportation, she began, made it inevitable that influenza would travel around the world, but the high degree of contagiousness of this iteration was something new. And the speed with which it could now turn from a fever to pneumonia to sudden death made it of the utmost importance for steps to be taken to contain it.

Unfortunately, she continued, the propensity of the Japanese to stick their heads in the sand instead of facing up to a problem had made a bad situation worse. “Why, “ she raged, “did not the government, early on, preventively order the temporary closing of places where many people gather in close quarters, like large dry goods stores, schools, places of entertainment, large factories, major exhibitions, and so on?” In twenty-first-century terms, she was pointing to the lack of proactive, strong leadership and the neglect of the need for social distancing and avoiding crowds. That was her first point.

Her second point was premised on the medical view that influenza, with its high fever, led to pneumonia, which led to death. Therefore, the most crucial medication was an antipyretic. Unfortunately, the best ones were too expensive for the poor, so Akiko recommended that the public and private sectors work together to supply them cheaply. In her signature fusion of classical and modern, Akiko concluded by quoting from ancient Chinese philosphers in support of her modern democratic ethos:

“Rousseau was not the first to discourse on equality. Confucius said, ‘It is not poverty I lament, but inequality.’ And Liezi said, ‘Equality is the ideal under heaven.’ In light of our new ethical awareness today, I think it is truly irrational that our fellow human beings should be deprived of the best medicine, and so endure even more suffering and anxiety, only for the material reason that they are poor.”

Akiko next discussed the pandemic in a section of “Oriori no kansō” (Thoughts and Impressions), published on February 12, 1919. By this time, the first wave had begun to wind down, but there was a slight uptick. “The global influenza has returned,” Akiko wrote, and reported that she and her husband had succumbed to it twice since last year, while the children too had caught it one after the other. What exercised her was the primitive state of urban hygiene, for example, the crowded street cars “like a box for forcibly infecting people with germs,” and their “filthy leather handstraps” that were never disinfected, not to mention the bad hygiene in schools: lack of proper heating, hand hygiene, and gargling. She deplored the Ministry of Education’s complete lack of interest in these problems, and declared that, even though she was a believer in kindergartens (a modern innovation), she was keeping her kindergarten-age son home from school.

Yosano Akiko in an undated photo. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

From mid-January the second wave was at its peak, and for a terrible three weeks the pandemic was at its height. The rate of infection was lower, but the mortality rate was much higher, and influenza was once again taking central stage in the newspapers. It was at this juncture, on January 25, 1920, that Akiko published “Shi no kyōfu” (The Fear of Death). Unlike the earlier two essays, which had been devoted to practical and medical matters, this was devoted entirely to the psychological effects of the pandemic. She began: “Seeing the ravages wreaked by the raging epidemic, how perfectly healthy people can become sick and die in five or seven days, one’s thoughts turn to the mutability of life, and to death itself. Ordinarily, we take life for granted and only think how we can live it best, but seeing this, we become like a Buddhist believer, terribly aware of the transience of life. Fear of death has come to occupy an even larger place in our awareness than the struggle for food that has consumed the lives of those who must work for a living, whether with their minds or their bodies, for the last four or five years.”

The climax of the essay is this brief passage: “Now we are surrounded on all sides by death. In Tokyo and Yokohama alone, four hundred people are dying every day. It may be our turn tomorrow, but until the very end, holding aloft the flag of Life, I want to defend myself wisely against this unnatural Death.”

She concluded by saying: “I have known the fear of death when giving birth, and also in response to today’s influenza epidemic, and it is at those times that I felt my desire to live deepen the most, not for my own individual self but for the sake of nurturing my children. When human beings become parents, they come to feel a different density, a new color, in their attachment to life. Love for the human beings that have come forth from one’s own body expands to include love for all of humanity.”

In the middle of the third wave, when the number of cases and deaths were decreasing, Akiko again touched on the influenza pandemic, this time as part of her essay “Eisei to chiryō” (Hygiene and Treatment, October 1920). Evidently by this time she had come to feel it was futile to ask the government to do more than it was doing, even though in her view it was far from enough. Her remarks are all about what individuals can do for themselves and their families, and her assumption is that influenza epidemics are here to stay (as indeed it has proven to be). Thus, she begins: “The season when the terrifying ogre of influenza awakens has come around again.”

In “The Fear of Death,” she had pledged to do the best that she, on an individual level, could do to resist the sickness. In “Hygiene and Treatment,” she tells us, in effect, how she is carrying out her vow. Her methods are almost the same as those in use today. First, came good nutrition, then gargling to wash away toxins, especially after returning home from being in crowds. She recommended that employees of companies and factories should all have gargling medicine and use it often while at work. Then she reveals that she also receives periodic injections devised by her obstetrician and longtime friend, Dr. Ōmi Kōzō. In spite of the fact that the general opinion among specialists was that “vaccinations” were useless, Akiko felt the efficacy of Dr. Ōmi’s injections was proven because none of his patients and no one in Akiko’s family came down with influenza. She then gave the address of Dr. Ōmi’s clinic for those who might want to try it. Here we see the practical side of our poet, devotedly caring for the health of her family.

Akiko took up the problem of death for the second time in “Shi no kyōi” (The Dread of Death), published on February 12, 1923. At the time, there seemed to be an unusual number of death notices and obituaries in the newspapers, and a doctor she knew told her that influenza was going around. Her own children were coming down with fever and coughs one after the other. Then, her family was notified that her husband’s nephew, a young doctor studying in Berlin, had died of pneumonia on the eve of his return to Japan. Here was a young person, not yet thirty, gone in an instant. The frailty of human life came home to her and she felt her own children might even be in danger.

The acceptance and calm with which Mori Ōgai (1862–1922), the great novelist and her good friend, had met death the year before filled her with admiration. People like him “do not fear death like an ordinary person. When death comes they die as though returning home.” But she did not believe such equanimity was possible for her. She was one of the “ordinary people” (bonjin) who feel intense anxiety about death. She concluded by giving the same reason she had given before, in “The Fear of Death”: as a parent, “I cannot afford to die.” And so, “As the mother I am now I would fight death to my last breath with no shame whatsoever for being an unregenerate coward.”

The celebrated author Mori Ōgai, pictured here in 1916, passed away at age 60 in 1922. (Courtesy National Diet Library)

And yet, there is something else here, for earlier in the essay, she talks about a general fear of death, which she ascribes to her age (she was then 45), the fact that paralytic stroke runs in her family, and the further fact that both of her parents died of cerebral hemorrhages. When she hears about the death of someone else, “I tremble as though it were a portent of my own death. My heart then seems to melt away like thin snow.” And yet, she continues, “From the depths of the heart so frightened and depressed by death, somehow a mysterious defiance and courage well up. I cannot die. No matter what, I must live.”

The rational reason, or the rationalization, may be the children: But there is this irrational and inexplicable boldness and courage, a kind of life force, that wells up in her in response to the dread of death, and whose source she does not even try to explain. In all her writings about the epidemic, this is the only mention of it, but it seems more basic to her nature than any other reason she gives.

In Akiko’s world, contagious diseases like cholera and tuberculosis were common. People died at home more often than at hospitals, so it is likely she had seen death up close, perhaps when she was nine and her paternal grandmother, who lived with her family, died. It was then that, by her own vivid account in Watakushi no oitachi (My Childhood), the child Akiko became aware of death and began to fear it. As an adolescent, she related in Aru asa (A Certain Morning), the fear of death came to obsess her, and then turned into a secret attraction. The darkness only lifted when she found poetry and love and, as she later put it, “danced out into the light.”

Yet the awareness of death lurking beneath the surface of life, sometimes a threat and sometimes an attraction, lingered on. Her pregnancies and birth were described in poetry and prose as confrontations with death from which she returned reborn. Her dread of death was definitely mitigated by the fierceness of maternal love, yet she also wrote poems during times of illness that describe a longing to give up and die, and others that describe dreams of a beautiful world beyond life. At the same time, at the moment of choice, death was always opposed by the mysterious will to live that welled up within her from she knew not where, something mysterious and bountiful. That is the Eros and Thanatos of Yosano Akiko.

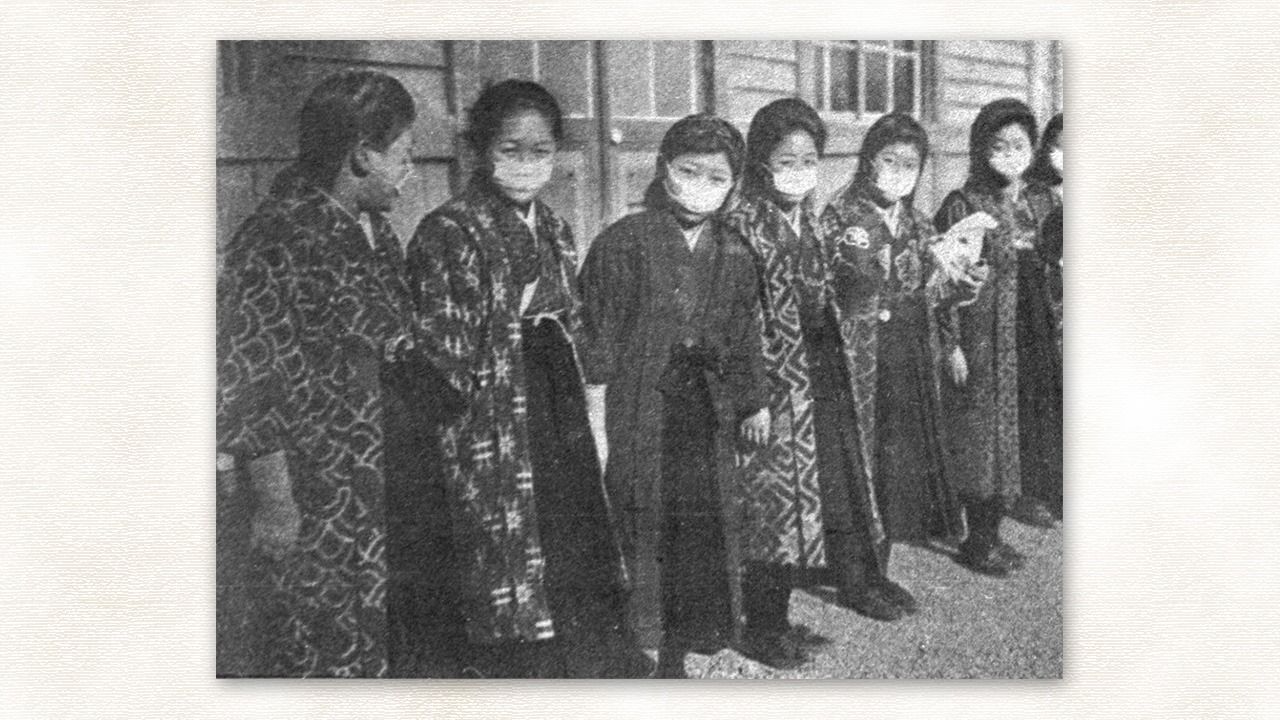

(Originally written in English. Banner image: Students wear masks to protect themselves from influenza in February 1919. © Mainichi Newspapers/Aflo.)

Scholar, translator, and poet. Professor emerita at Daitō Bunka University. Author of the Nō play Drifting Fires. Books include Masaoka Shiki: His Life and Works, Embracing the Firebird: Yosano Akiko and the Rebirth of the Female Voice in Modern Japanese Poetry, and Beneath the Sleepless Tossing of the Planets: Selected Poems, a translation of poetry by Ōoka Makoto for which she received the Japan-US Friendship Commission Prize for the Translation of Japanese Literature. Her most recent publications are the 2021 Well-Versed: Exploring Modern Japanese Haiku, a translation of Meiku no yuen by the haiku poet Ozawa Minoru, and the 2022 This Overflowing Light: Rin Ishigaki Selected Poems, her translations of Ishigaki Rin’s poetry. Her work has been supported by awards from the National Endowment for the Arts and America PEN, among others.