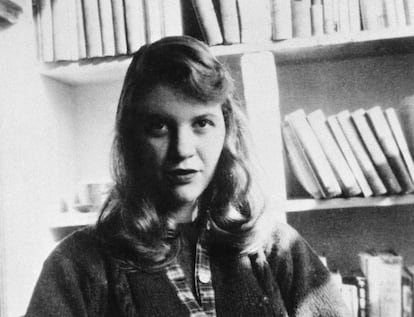

Joy Harjo, in an image from 2019, after becoming the 23rd United States Poet Laureate. She is the first Native American to have ever held the honor

Joy Harjo, poet: ‘The land does not belong to us; we’re just its stewards’

In her interview with EL PAÍS, the writer — the first Native American to be honored as United States Poet Laureate — reflects on the place of Indigenous peoples and poetry in society. She also sounds the alarm: ‘Acting without respect for the environment has its consequences’

IKER SEISDEDOS

Washington - NOV 08, 2024 - 23:05

Joy Harjo is one of the most respected poets in the United States. A member of the Muscogee Nation, in 2019, she became thefirst Native American to be named the Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress, commonly referred to as the United States Poet Laureate. She renewed this honor twice, holding it until 2022. Other writers who have held the title include Elizabeth Bishop, Robert Frost, Nobel Prize winners Louise Glück and Joseph Brodsky, as well the incumbent, Ada Limón.

In addition to being a poet, Harjo is a saxophonist, singer, artist and playwright. She has collected her memories of an intense life in two volumes of memoirs: Crazy Brave (2012) and Poet Warrior (2021). Her existential journey led her to live in various states — including New Mexico, Iowa, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Colorado and Tennessee — before she returned to Tulsa, Oklahoma, where she was born in 1951. She grew up there under the shadow of an abusive father, before leaving for university in Santa Fe. There, she discovered her literary calling.

Harjo is the author of 10 collections of poetry and a handful of children’s books, non-fiction titles and plays. She has also published seven musical albums. In October, she received the National Medal of Arts from President Joe Biden in a private ceremony at the White House. A couple of weeks later, Biden traveled to Arizona to offer an apology for the federally-run boarding school system that, for decades, tore Indigenous children and young people away from their families. These youths were held in facilities where their customs and languages were prohibited, in order to assimilate them into the dominant white culture.

Question. How would you define the place of Native Americans in American society?

Answer. It’s a complicated space, although things have changed a lot since I came into this world. Racism and a caste system that organizes society based on money persist. But sometimes, generations bring about change… and sometimes, those changes are destroyed by those who want to maintain power or maintain their greedy structures.

Q. Was it easy for you to have your voice heard when you started writing poetry in the mid-1970s?

A. As Natives, we’ve always been at the mercy of waves of recognition from the “other.” I was fortunate to study at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico, which was a liberal arts school that was at the center of a cultural movement. After the occupation of Alcatraz [which lasted 18 months, between 1969 and 1971] and the explosion of the Native rights movements, one of those waves of recognition was generated. Then, attention came back to us after Wounded Knee [the 1973 takeover of the town of the same name in South Dakota by activists from the American Indian Movement]. Years later, it was Standing Rock [the 2016 protest against the construction of an oil pipeline in Sioux territory in North Dakota].

It always happens like this: a certain recognition comes along, and then, we’re forgotten for a while. In 2020, the Supreme Court ruling [which ruled that almost the entire eastern half of Oklahoma is Indigenous territory] was key, as was the[murder of] George Floyd. In recent years, there have been advances in the cultural field: the series Reservation Dogs, the Oscar nomination for actress Lily Gladstone, my consideration as poet laureate…

This time around, I think the attention will persist, because Native Americans are intrinsically linked to what it means to be American.

Q. Where do you see the country heading?

A. I’m a child of the civil rights era. I fought for the rights of Indigenous peoples, I grew up surrounded by poets and thinkers from the Chicano movement and all the others who fought to change things. Seeing women’s rights being dismantled now saddens me. It makes me think that we’re at a crossroads. And not just in this country, because the whole world is connected to each other, we’re all connected to what it means to be human. Global warming, economic systems that stopped taking care of us and only looked after the rich... we’re watching a major shift go down.

Q. Some of the historical Native leaders inspired the emergence of the environmental movement that’s currently being led by the youth.

A. You don’t have to go back to the wisdom of our ancestors to understand that it’s not a good idea to take from nature more than you’re going to use. You have to act with respect. The land doesn’t belong to you. We’re just its stewards. We live in a world dominated by a power system that behaves in a greedy way, that digs and digs and destroys river ecosystems, fisheries and everything else. It’s gone too far. There’s a delicate balance in this world, and it must be preserved. Animals, plants, insects, human beings, rain, mountains… we’re all part of a bigger story. When we act without respect, there are consequences.

Q. Did you enjoy Killers of the Flower Moon, Martin Scorsese’s latest film?

A. Yes and no. I don’t think it’s my place to be a film critic. Let’s just say that it’s an important film, but at the same time, it’s the classic film dealing with Native American issues, when the main characters aren’t Native Americans.

Q. Was the plundering of the Osage Nation— which is described in the movie — an incident that was sufficiently well-known among Native Americans?

A. Among us, yes. The same thing happened in our Muskogee Nation [both are in the state of Oklahoma]. Part of the land my family was allotted turned out to contain one of the largest oil fields in the world. They say it was like a lake of oil. My great-grandparents were millionaires, and my grandfather was the first to own a car. When my father died and we inherited his oil shares, they were worth about $30 a share. Then, they sent us a letter and told us that those mineral rights had been sold. I’ve never looked into it enough, but clearly there was a lot of corruption. There were murders here, too. And one woman — who was one of the richest women in the world — was given a legal guardian, because at the time, if you were a fullblood Native, it was thought that you didn’t have the capacity to take care of your land.

Q. When did you know you would be a poet?

A. As a child, I didn’t aspire to be one, because I didn’t know that Natives could do that. Painting was a possibility, because my grandmother painted. I didn’t decide to write until college, when I started hanging out with other poets. That’s when poetry took hold of me.

I was a single mother with two children. How was I going to make a living? But that didn’t matter: once it took hold of me, I didn’t do anything else. In the end, luckily, I managed.

Q. One of your first dreams was about Emily Dickinson. You’ve written that you identified with her idea of being a nobody.

A. I really liked Dickinson as a child. I still love her. She was an original poet. That’s something I’ve always sought, in writing or in music: not to look like anybody else.

Q. Over the years, you became a somebody. In 2019, you were named the United States Poet Laureate.

A. You don’t dedicate yourself to poetry to achieve something like that. You do it because it’s what moves you. Poetry gives you something. For me, it isn’t limited to books. Rather, it’s an art connected to music and dance.

Recognition was never easy for Native writers. When I was in college, I remember going to look for N. Scott Momaday’s novel that won the Pulitzer Prize [House Made of Dawn in 1968]. And seeing that it wasn’t in the literature section, but in the anthropology section, we were often pigeonholed into non-literary categories.

It was a surprise when I got the call about the award. I thought I was being called by the Library of Congress to participate in a festival they organize in the summer every year. By then, I already had an audience. That’s when the recognition came.

Q. What role does poetry play in Native communities?

A. I’ve traveled around the world, and I’ve been able to see that poetry is more central in other societies than in the American one. During the pandemic, however, people sought refuge in poetry, in the same way that we turn to it in the special moments of our lives. Many of my classmates at art school were less than a generation away from what we call the “generation of orality.” That includes an awareness of the power of orality. Poetry is part of that. Some of that has been lost with the digital revolution.

EL PAÍS