|

| Anna Akhmatova |

|

| Anna Akhmatova |

The following is a guest post by Munazza Ebtikar, a Ph.D. Candidate at the University of Oxford and a native of Balkh and Panjshir, Afghanistan. She tweets at @mebtikar.

سر انگشت در خون میزد آن ماه ز خون خود همه دیوار بنوشت

The moon-faced beauty struck blood with her fingertip

With her blood she covered the walls

بدرد دل بسی اشعار بنوشت چو در گرمابه دیواری نماندش

Many poems stemmed from her agonized heart

When no walls remained in the hamam

ز خون هم نیز بسیاری نماندش همه دیوار چون پر کرد ز اشعار

So, too, a few drops of blood remained

As she covered the walls with poetry

فرو افتاد چون یک پاره دیوار میان خون و عشق و آتش و اشک

She collapsed like a fragment of a wall

Amid blood, love, fire and tears

بر آمد جان شیرینش بصد رشک

Her sweet soul swiftly left her body with a hundred desires.

-Sufi poet Farid al-Din Attar in the Ilahi-Nama

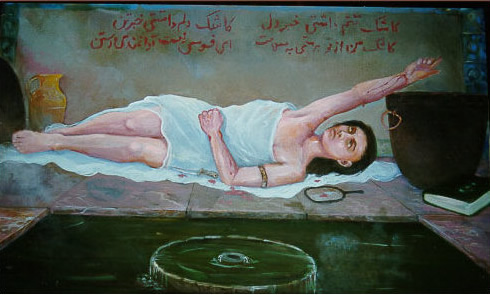

“Rabia slits her wrists so she can write her final love poem on the walls of the hamam with her blood,” narrates my aunt, sitting cross-legged on a red Afghan rug, designed with repeated octagonal patterns. We are in her daughter Rahima’s house in Khair Khana, a neighborhood in the north of Kabul. The sun rays cast a halo on her braided white-peppered brown hair. She balances a glass filled with steaming green tea in one hand, while the other raises a pink fly swatter in the air. Her eyes search for the buzzing menace and shift to mine, anticipating a reaction. I give her a knowing look of acknowledgment at the story’s tragic end. Her eyes search around the room as she explains the final act in a raised voice. “It must be understood: Rabia did not kill herself for Baktash.” She looked at me again. “She found love in God through Baktash; her heart was too pure in the face of injustice, you see.”

My aunt is narrating the tragic love story of Rabia Balkhi, a medieval poetess from Balkh, located in present-day northern Afghanistan. Rabia is one of the most venerated female figures in the Afghan imaginary. She is credited with having been among the first practitioners of New Persian or Parsi-ye Dari (tr. Persian of the Court). The language flourished in the 10th century after two centuries during which the Islamic conquest transformed the region’s cultural and linguistic composition, infusing Middle Persian (Pahlavi) with new vocabulary and a new script. Rabia was a poet princess in the Balkh court where her father served as Emir. She fell in love with her brother’s Turkish slave, Baktash, and would write poetry to him. Because of her brother’s jealousy and wickedness, he cast Rabia into the hamam and Baktash into a well. In the hamam, Rabia slit her wrists and with her blood she wrote her last love poems until her death.

“You see they don’t tell you, her love for Baktash is not like what you see in these TV shows.” We both glance at the Persian-dubbed Turkish show playing on the TV screen. The picture is blurry, but one can make out a man gazing into the hazel eyes of a beautiful Turkish woman. “She was a pure woman. Her burial site is a sacred shrine. I’ve been there,” my aunt says, nodding her head. My aunt narrates Rabia’s love story by adding her own emphasis on what she finds significant, providing her own interpretation of the story. For my aunt, Baktash was the means by which Rabia could reach the divine. It is common to hear Afghans tell and retell her love story with different emphases, reflecting on the world around them to make sense of themselves and their lives in a specific time and place. Rabia is depicted as a feminist icon who spoke truth to power, a martyr for sacred love, or even a victim of honor within a patriarchal order.

Today, Afghans name their daughters and institutions – from schools to hospitals – after her. Monuments were built in her honor and her story became a part of Afghanistan’s national culture through theater performances and film productions such as the historic epic Rabia Balkhi (1974). More than a thousand years after her death, Rabia continues to figure strongly in the Afghan cultural imaginary.

Although Rabia remains prominent in Afghan popular memory, her life and poetry have not been subject to much scholarly inquiry. In fact, there are scant references and illustrations of her life in literature on Persian poetry in most languages, even in Persian. Scouring through bookshops and libraries in Kabul in 2019, I was able to find only a few works on Rabia. There were some illustrations of her love story in some books and some collections of excerpts of her poetry or, perhaps, poetry attributed to her. How then, do we know about Rabia’s poetry and love story? Why does the afterlife of her love story remain prominent in the Afghan oral tradition? And what do the differing accounts of her love story tell us about the ways in which Afghans imagine themselves?

Although no divan of Rabia’s work exists, Rabia’s story and her poetic verses appear prominently in the narrations of influential male Persian poets and biographical dictionaries (tazkirahs). The earliest biographical work of Persian poets, titled Lubab al-albab (tr. The Essence of Essences) written by Muhammad ‘Awfi (1171-1242 CE) in 1220, briefly mentions Rabia, her skill in Persian poetry and her intellect under the title Rabia bint Ka‘b al-Quzdari. The longest narration of Rabia’s life and poetry is in the lyrical poem of the Ilahi-Nama (tr. Book of the Divine) by the Sufi poet and hagiographer, Farid al-Din Attar (1145-1221 CE).

One of the mystical stories in the Ilahi-Nama is of the life and poetry of Rabia titled Hikayate Amir-e Balkh wa āsheq shudan-e dukhtar-e ō (tr. the story of the Emir of Balkh and his daughter falling in love). As the longest narration of her story and poetry, Attar narrates her story and poetry as a mystic, a common trend among Sufi poets after her time. Her love for Baktash, her brothers’ Turkish slave, is depicted as sacred and divine love, as it is through seeing him that she starts writing her love poetry and only through him that she experiences this love for the divine.

Attar claims that it was the Persian Sufi poet Abu Sa‘id Abul Khayr (967-1049 CE) who had informed him that Rabia became a mystic and that her poetry was for God. This story of love and sacrifice has parallels to that of Rabi‘a al-Adawiyya (714-801 CE) from Basra, one of the most prominent female saintly figures in Islamic history, renowned for her unwavering devotion to God. About 270 years after this narration, Nur al-Din Abd al-Rahman Jami (1414-1492 CE), the 15th century Persian Sufi writer and poet, mentions Rabia in the hagiography titled Nafahat al-Uns (tr. Breezes of Intimacy), mentions Rabia among thirty-three other female saints under the title Dukhtar-e Ka’b, Rahmat-ullah alayh (tr. The Daughter of Ka’b, May God Have Mercy on Her). In this passage, Jami also references Abu Sa’id Abul Khayr’s story, writing that the daughter of Ka’b was in love with the slave but her love was not for him. Building on the same tradition as Attar, he writes that when Baktash saw Rabia close to him, he laid a hand on her sleeve. In response, she scorned him and said, “Is it not enough for you to understand that this love is for God? Have I given you the occasion to enjoy me?”

From these textual accounts, we can infer that Rabia lived during the Samanid Empire, which stretched from Transoxiana to Khorasan in the 9th and 10th centuries. At the time, Balkh served as one of the empire’s main cultural centers and as the epicenter of Islamic scholarship and mysticism. It was home to great poets and Sufi masters, gaining epithets such as umm al-bilad (tr. the mother of cities) or qubbat al-Islam (tr. the dome of Islam). Rabia was the daughter of Ka‘b, a local Emir, and of Arab lineage. As an outcome of the Islamic expansion eastward, Balkh had become an important center of Arab settlement in the 8th century. As the daughter of an Emir, Rabia occupied an elite position as a member of the nobility and was educated and wrote poetry.

Unlike male poets, such as her contemporary Abu ‘Abd Allah Ja‘far ibn Muhammad Rudaki, who served as poet laureates in the court and were compensated for their literary services, female poets wrote more for individual desire. Rabia wrote in both Persian and Arabic. Her poetry has served a crucial and decisive role in the revival of Persian poetry as we know it today: it alludes to pre-Islamic kings and religions, and uses tropes and metaphors which recur in later Persian poetry. It is for this reason that Rabia remains a central figure in the making of the Persian literary tradition. Born three centuries before Jalal ad-Din Mohammad Balkhi (commonly known as Rumi), Rabia was a major contributor to the foundation of the Persianate literary canon.

What we know of Rabia’s poetry and life in textual accounts has been passed down by Sufi chains of transmission, all of which emphasize her sainthood. In circumstances where oral transmission is broken or a divān is lost, tazkirahs become the “sole repositories of memory about some individuals and fragments of their verses.” Tazkirahs, according to Zuzanna Olszewska, “offer useful insights into the changing ways in which public narratives of distinction, or the distinctiveness of literary personalities, could be constructed and the types of people whose distinctiveness could be claimed.” Perhaps it is this emphasis on her sainthood that may explain why her mausoleum today, located in Nawbahar in Balkh, is one of the most frequently visited sites by pilgrims, tourists, and locals alike. Nawbahar itself is a famous pilgrimage site comprising tombs of pious men and women. This site holds a sanctity that predates Islam as it was also a spiritual site for Buddhism and Zoroastrianism.

Afghans tell and retell Rabia’s story and poetry through diverse avenues, and in diverse social and political contexts. Rabia is memorialized and immortalized by her narrators. Olszewska describes composing and writing poetry in Afghanistan to be “the most highly prized and widely practiced art form among Afghans of all walks of life, both literate and illiterate.” In one sense, Rabia’s popularity in Afghanistan is like Ferdowsi’s in Iran, which, as Aria Fani writes, was “the product of intellectual and architectural labor sponsored by the state.”

Afghan nationalists in the 20th century worked to create and promote a distinctive “Afghan” national and historical identity, privileging their own canon of writers whose birth fell within the borders of the nation-state. This explains why one of the first government-sponsored Afghan films was on Rabia and why many all-women institutions, such as schools and hospitals, were named after her. But, in another sense, Rabia’s love story with Baktash resembles the great tragic love stories of Persian literature – such as Leili and Majnun or Khosrow and Shirin – allowing it to be easily narrated and passed down from one generation to the next.

My aunt in Khair Khana retold Rabia’s story to make her own point about the power of love and God. For my aunt, Rabia’s love contrasted with the modern-day love portrayed in the Turkish serial drama airing on the small TV set in front of her. Yet, hers is only one version of Rabia’s love and life represented in the Afghan popular imaginary. In her exhibition of notable women in Afghanistan and the region “Abarzanan” (tr. Superwoman), held in Kabul in 2018, Afghan artist and photographer Rada Akbar displayed a red dress to represent Rabia. She described Rabia as “a symbol of defiance against patriarchy and a continued harsh reminder of the price we’ve [Afghan women] been forced to pay for freedom of speech and love.”

This has parallels to an article written on Rabia published in the popular magazine, Zhvandun, more than 40 years prior in 1974. The first line of this article reads, “the story of Rabia is the story of a cry in the strangled throat of the women in our society in her time and other times that have passed.” Although 40 years apart, both interpretations reflect on the dire place of Afghan women within a patriarchal society – as well as how Afghan women have claimed Rabia’s legacy as a means of resistance.

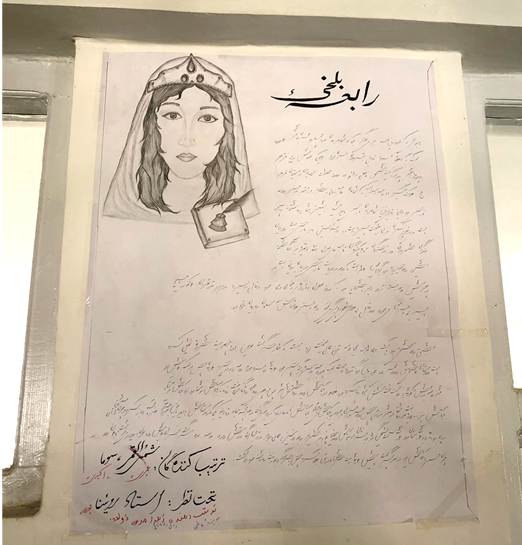

Julie Billaud, in her ethnography titled Kabul Carnival: Gender Politics in Postwar Afghanistan, notes the popularity of Rabia among female students at Kabul University. They admired Rabia’s heroism in choosing self-sacrifice and death to defend greater ideals. Self-sacrifice, according to Billaud, is part of these Afghan women’s broad repertoire of emotional performance. Comparingly, when I visited all-girls schools in Kabul and Panjshir in 2019, descriptions or drawings of Rabia adorning hallway walls (See Figure 6) was a common sight. Rabia’s legacy inspires young women to defy and transcend the unjust limitations placed – and worldviews held – within their society. As such, Rabia’s defiance and bravery to reach her earthly love, Baktash, the divine, or both, in her life and her poetry remain central in the Afghan cultural imagination one thousand years after her death.

Although Rabia’s story takes many forms, her story which I heard told and retold in Afghanistan has a common version, and it goes as such.

In the sacred land of Balkh with its one thousand mosques, Rabia, the daughter of the Emir of Balkh, is born. She is bathed in rose water, adorned in silk, and placed in a carriage made of gold. The day of her birth is celebrated by the people of Balkh, and they rejoice as they pray and read poetry on this auspicious day.

Rabia is raised in the palace where she is taught arts and literature, hunting and archery, until she reaches the age of wisdom. She was enchanting, both in her beauty and her words. She moved and spoke with an eloquence that left her with many admirers. When Rabia recited her poetry, it would bewilder the poets and literati of her time. She captured not only the hearts of her mother and father, but the people of Balkh themselves nicknamed her Zain al-Arab (the beauty of the Arabs, or the most beautiful one of the Arabs), Iqbal (the auspicious), and Tela-ye Ka‘b (the gold of Ka‘b). Her youth and charm would illuminate the eyes of her aging father.

One day, a famous astrologer of Balkh named Atrosh tells her that although she is an irradiating star and will set the world aflame with her passion, she may fall into bad omen.

Rabia’s mother passes away and this shatters her delicate being. The women of her court took Rabia to places of worship so that her soul was soothed by the sermons and verses of the great scholars and men of wisdom from Balkh.

Meanwhile, her brother Haris was jealous and envious of Rabia’s skill, eloquence, and the admiration she received from her father and the people of Balkh. When their father is on his deathbed, he calls them both to him. He tells Haris that he will be his successor and advises him to be just and generous with all of God’s creations, and to ensure that he will look after Rabia.

∙∙∙

One day as Rabia stands on her balcony overlooking a garden, she catches sight of a beautiful man serving wine to Haris. Baktash, Haris’s Turkish slave and a guard of the treasury, captures Rabia’s heart. This moment marks the beginning of Rabia’s love story and poetry, and her tragic fate.

Rabia would compose love letters to Baktash in verse, longing for him. These would be delivered by her loyal court maiden and friend, Ra‘na. Her love for Baktash was an affliction that no doctor of Balkh was able to cure.

Rabia writes:

الا ای غائب حاضر کجائی

Oh the absent and present one where are you

به پیش من نهٔ آخر کجائی

If you are not with me then where are you

دو چشمم روشنائی از تو دارد

My eyes are illuminated by you

دلم نیز آشنائی از تو دارد

My heart is acquainted by you

بیا و چشم و دل را میهمان کن

Come and invite my eyes and soul

وگرنه تیغ گیر وقصد جان کن

Otherwise take a sword and end my life

Baktash, in response, says:

ندارم دیدهٔ روی تودیدن

I don’t have the sight to see you

ندارم صبر بی تو آرمیدن

I don’t have patience and rest without you

مرا اکنون چه باید کرد بی تو

What am I going to do with you now

که نتوان برد چندین درد بی تو

How can I carry this pain without you

چو زلف تو دریده پردهام من

Your hair has pierced my veil

که بر روی تو عشق آوردهام من

With your face I have fallen in love

ازان زلف توام زیر و زبر کرد

From your hair I have become under and over

که با زلف تو عمرم سر به سر کرد

Because from your hair my life has been destroyed

∙∙∙

During this time, Asher al-din, the ruler of Kandahar, sought to attack Balkh and subject it to his rule. Haris, who had claimed his throne, was fearful and prepared to stand in opposition. With the consultation of his advisors, he knew that without the help of Baktash, he was unable to defeat his enemy.

Haris tells Baktash that if he kills Asher al-din, he will reward him with what he pleases. In the battlefield Baktash was victorious but at a dear price. As he nearly lost his life, a soldier with a covered face came galloping into the battlefield to save him and win the war. This soldier was none other than Rabia.

∙∙∙

Balkh was the epicenter of literary events, but it was unmatched by Bukhara. Amir Nasr, the king of the Samanids, was a lover of poetry and organized grand literary events in Bukhara, the home of the great poet, Rudaki. One day, Haris was invited, together with the newly defeated Asher al-din of Kandahar, the ruler of Herat, and other notables, to witness Rudaki recite his poetry.

When Rudaki recited his poetry, he dazzled his audience. One of his poems was Rabia’s, whom he would join in the Balkh court. After he recites her poem, he attributes it to her and says that although Rabia is a sacred woman, she fell in metaphorical love with her slave Baktash, the inspiration behind this poem. When Haris hears this, he coils like an injured snake. The event comes to an end and Haris takes towards Balkh, thirsty for the blood of Rabia and Baktash who had brought shame to his name.

Upon his arrival to Balkh, Haris orders that Rabia be thrown in the hamam and Baktash in a well. In the hamam, she slashed her wrists, and writes the last few lines of poetry for Baktash with her blood on its walls. After days of being in the well, Baktash is saved with the help of Ra‘na. He first takes Haris’s head and goes to the hamam, only to find Rabia’s beautiful lifeless body on the ground covered with her blood and the walls of the hamam adorned with her last love poems for Baktash. He falls to the ground and takes his life next to his beloved.

One of the poems that are on the wall reads:

کاشک تنم يافتي خبر دل

I wish my body was aware of my heart

کاشک دلم داشتی خبر تن

I wish my heart was aware of my body

کاشک من از تو برستی به سلامت

I wish I could escape from you in peace

آی فسوسا کجا توانم رستن

Where can I go regretfully

References

Azad, Arezou. Sacred Landscape in Medieval Afghanistan: Revisiting the Faḍa’il-i Balkh. Oxford University Press, 2014.

Billaud, Julie. Kabul Carnival: Gender Politics in Postwar Afghanistan. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015.

Davis, Dick. The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women. Penguin Books, 2019.

Olszewska, Zuzanna. “‘A Desolate Voice’: Poetry and Identity among Young Afghan Refugees in Iran,1.” Iranian Studies, vol. 40, no. 2, 2007, pp. 203–224.

Olszewska, Zuzanna. “Claiming an Individual Name: Revisiting the Personhood Debate with Afghan Poets in Iran.” The Scandal of Continuity in Middle East Anthropology: Form, Duration, Difference, edited by Judith Scheele and Andrew Shryock, Indiana University Press, 2019.

This essay is based on a talk presented at Stanford University on February 21, 2012 by Majid Naficy.

Los Angeles is sometimes called Irangeles, because more than half a million Iranians live there. Most of them have come to this city during or after the 1979 Revolution. They were either beneficiaries of the fallen monarchy or supporters of the revolution who became disillusioned and suppressed by the rising theocracy. Soon after arrival, Iranians established Persian radio, television and newspapers as well as bookstores and music shops in Los Angeles.

Iranians are very proud of their classical poetry and consider the national epic of The Shahnameh, composed by Ferdowsi a thousand years ago as the symbol of their nationality. Therefore, it is not surprising that covering Persian poetry in Iranian media, selling classical collections of poetry in bookstores and teaching Rumi and Hafez in private classes spread rapidly among Iranians in Los Angeles.

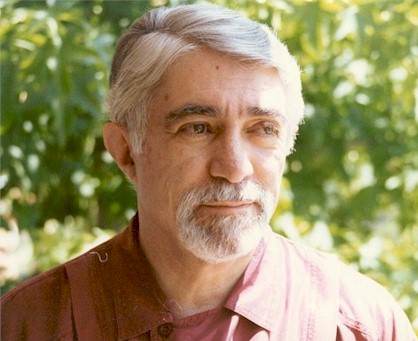

Today, the Iranian community in LA has many poets. Some of us, such as Nader Naderpour, Partow Nuriala, and myself had published collections of poetry at the time of the Shah in Iran. Others, like Abbas Saffari and Liela Farjami publish books of poetry both in Los Angeles and Tehran. Katayoon Zandvakili and Sholeh Wolpe write poetry only in English. Azadeh Farahmand writes poetry in both languages. I myself compose poems first in Persian and then translate them into English.

Fourteen years ago, on March 20, 1998, I hosted a poetry reading in celebration of Persian New Year in Beyond Baroque Literary/Arts Center in Venice Beach in which five poets, Nader Naderpour, Partow Nuriala, Mansour Khaksar, Abbas Saffari and myself read poetry in Persian and English. My late friend Harriet Tannenbaum read the English versions of Naderpour for him. Today, two of these poets are no longer living. Naderpour passed away in 2000 and Mansour Khaksar committed suicide in 2010.

In order to show you a sample of Persian poetry in Los Angeles, I would like to revisit these five poets and share a poem by each with you. By selecting these poems, I do not want to ignore other poets whom I have already mentioned or other poets such as Hamid-Reza Rahimi, Yashar Ahad-Sarmi, Khalil Kalbasi, Fazlloh Rowhani, Mortaza Miraftabi, Fariba Sedighim, Farzad Hemati, Sheida Mohamadi, Ali-Reza Tabibzadeh Behzad Razaqi, Manuchehr Kohan Freeda Saba, and Mandana Zandian who have published collections of poetry in Los Angeles. Hopefully one day I will be able to publish an anthology of Persian poetry in Los Angeles and include the works of all my fellow poets.

In this brief study, I focus on one question: are these poets still dreaming of going back to their homeland or have they come to some degree of acceptance of their adopted country?

Neither of these two tendencies has artistic merit over the other one. Nostalgia and adaptation are two common moods among human beings and both can become the subject matter of poetry. Perhaps, nostalgia is not a good recipe for an exile who cannot go back to his or her homeland. But it is definitely as interesting as cultural adaptation for a poet to write about. In Western poetry, we have, on the one hand, Homer’s The Odyssey in which a victorious but cursed-upon hero of the Trojan war longs for his homeland and, on the other hand, Virgil’s The Aeneid, in which the losers of the same war sail to a new land, Italy, and make it their new home. We need both of these epics, because nostalgia and adaptation are both parts of human migration and exile. Among our five poets, Naderpour is the one who never comes at peace with Los Angeles. Next to him is Mansour Khaksar who in spite of calling one of his collections of poetry Los Angelesinos remains apart from this city. (1)

Nader Naderpour was born in 1929 in Tehran and published his first poems in the newspapers run by the Soviet-oriented Tudeh Party in the 1940s. In the introduction to his first collection of poems Eyes and Hands (chashmha va dastha) published in 1954, he rejected the modernist poetry of Nima Yushij (1896-1960) in which classical meter and rhyme are “broken”. Instead, he adhered to the neoclassicist poetry of Mohammad-Taqi Bahar (1885-1951) in which only diction and imagery are updated and the traditional prosody is kept intact. (2) In the 1960s and 70s Naderpour worked as editor of two prestigious art magazines published by the Ministry of Art and Culture, as well as the chief of Contemporary Literature Division in Iranian National Radio and Television. At the same time, he was one of the signatories of Iranian Writers Association in 1968 who opposed state censorship. In 1980 in opposition to Khomeini’s regime he traveled to Paris where his daughter lived. Finally, in 1987 he moved to Los Angeles.

While in exile, Naderpour published three collections of poetry of which False Dawn (sobh-e dorughin) has been translated into English by Michael Hillman in 1986. In Los Angeles, Naderpour worked with Persian radio and television broadcasting from Los Angeles as well as Persian exile magazines published in other cities. He taught classical Persian poetry to Iranians mostly outside of academia. In his introduction to his last collection of poems Earth and Time (zamin va zaman) published in 1996 in Los Angeles, Naderpour accepts that Nima Yushij’s innovation in Persian poetry was a “social necessity” and Naderpour himself began to compose poetry in the style of modernists. Most of the poems in this collection are dark and reflect the poet’s fear of old age and death as well as longing for his homeland. In fact, the title of the collection Earth and Time expresses the anxiety of the poet for losing his youth and land. Naderpour’s nostalgia is sometimes accompanied with hatred toward his adopted city, as seen in “The American Night” written in December 1994. Here, he compares the “city of angels” (Los Angeles) to a “hell” and its inhabitants to “satans” and “quasi-human”:

The American Night

The place of my exile

Is a city on the shore of a Western sea

With old palm trees and new palaces

Taller than imaginary giants.

This city for greedy earthlings

Is home to the angels

But it is a hell with the beauty of the paradise

That from the beginning of illusionary cosmos creation

Has allowed satan to its solitude.

These human-like creatures who occupy this city,

Oblivious to destiny of their ancestors

Are longing for another forbidden fruit.

Today, at nightfall

The old sun in the burning fever of madness

From the peak of the greatest skyscraper

Threw itself on a sea cliff and died.

And yet, the tall city windows

Do not believe its black death

As if, they are

Waiting for a miracle from the East.

After its death

There is no star in this exile night

Because all stars are lost

in the warm smoke of clouds

And the spark of their delicate gazes

Are only hidden in the small raindrops,

As pure as the pigeons’ eyes.

In a night more naked than a black marble

I walk on a carpet of autumn leaves

With my gaze at the passing birds.

The tears pouring from the sky

And dripping into my gazing eyes

Resemble pieces of glass that through them

stones, plants, animals and men all look drenched.

I inhale the scent of the earth through fall breeze

And drink it as bitter wine,

In memory of my ruined mother land

And I begin to cry.

This time, through my eyes

From behind their tears, not from clouds’ tears

I see vividly that on both sides of the road

The colorful images of a hundred city lights

Are floating on the rain water puddles.

I open a path toward my home

In the empty streets of this city full of trees.

Amidst the humming wet branches

And become weary

From the footsteps of a stranger

Who in the middle of night is accompanying me

Without being my companion

Although our steps are the same.

Suddenly, over the faraway trees

The thick smoke of clouds

Begin to scatter by the attack of winds.

Night also, ironically

exposes in front of me

The unmasked moon’s coquettish face

And a masked attacking thief.

Staring at the handgun of this robber

I realize that in the city of angels

Satan and God are brothers. (3)

Mansour Khaksar was born in 1939 in Abadan. In the early 1960s he co-edited a southern literary magazine with the well-known writer Nasser Taghvai. Khaksar was arrested in 1967 and imprisoned for two years because of his Marxist Tendency. Two years later, he wrote a long poem The Story of Blood (karnameh-ye khun) and published it anonymously. It represented the feelings of young Marxist revolutionaries called People’s Fadaee Guerrillas who took arms against the Shah’s regime in the early 1970s. In 1975 he traveled to London and worked as a bank accountant while pursuing his clandestine activities for Fadaee’s organization. When revolutionary poet Sa’id Soltanpour (1940-81) was released from prison and went abroad, he and Khaksar with three other activists who had suffered the Shah’s political prison, established a committee called From Prison to Exile (az zendan ta tab’eed). This committee organized many gatherings in support of the rising revolution in Iran. Before the collapse of the monarchy, Khaksar returned to Iran and became one of the founders of Fadaee’s organization in southern Iran. When Khomeini’s regime began to suppress the opposition, he fled to Soviet Azerbaijan in 1984 and two years later went to Germany. Upon separation from his wife, Khaksar moved to Los Angeles in 1990 where he worked as an accountant until his suicide in March 2010. He is survived by two daughters. Khaksar co-edited daftar-ha-ye shanbeh and daftar-ha-ye kanun the journals of a literary circle in Los Angeles and the Iranian Writers’ Association in Exile respectively, as well as the poetry section of Arash magazine published in Paris. He published a dozen collections of poetry in Los Angeles, including qasideh-ye safari dar meh (The Ode of A Journey in Fog) in 1992 and losanjelesi-ha (Los Angelesinos) in 1997. (4) In the first book, a long narrative about his coming to exile, Khaksar breaks with his group mentality in the past and searches for his own individuality. In the second book, which consists of 23 connected short poems, he often expresses loneliness and isolation in exile and longing for his homeland. In one of these poems (p. 32), which he has written in Santa Monica beach, he reminisces of his youth in Abadan at the Persian Gulf while looking at the Pacific Ocean:

I am staring at the ebbing sea

And the winter sun

Has made me naked.

I am fully revealed

Like a worn-out book.

I am a ruined past

From a distant tribe

Whose palm trees make me naked

In the arms of water and fish

And seamen’s hums

And an aging memory

With no rain on high hills.

The night is approaching

And I am standing against it

With bitter resources

That kindle no lamp.

Where is my youth At twenty?

When I stepped upon the horizon

And set fire to the house

With no fear of tomorrow.

A crescent moon has opened arms in solitude,

But does not camp within me.

For hours

I’ve been floating on the shallow water

And the nightly world has been chasing me.

To count the delays of returning home

I plant the paddle of wind in the water

And grow in its sail.

My vision is blurred

I have made the sky cloudy

And sail aimlessly. (5)

Partow Nuriala was born in 1946 in Tehran. Her first collection of poetry sahm-e salha (A Share of the Years) was banned in 1972. She played in the movie aramesh dar hozur-e digaran (Calmness In the Presence of Others) directed by Nasser Taghvai which was also banned. Nuriala earned her BA in Philosophy from Tehran University and later taught a course in the same field. Her husband was the well-known poet Mohammad-Ali Sepanlou. She moved to Los Angeles in 1986 with her two children and worked as a Deputy Jury Commissioner at the Los Angeles County Superior Court until retirement. In addition to a book of literary criticism, Partow Nuriala has published five collections of poetry of which the first two volumes are mostly related to social issues before and during the revolution. Her latest collection az dar ta bahar (From Gallows to the Spring) contains poems written after the 2009 June uprising in reaction to presidential election rig. She considers herself a feminist and two of her longer poems “I Am Human” and “Four Seasons” relate the story of a woman in a patriarchal society. In her poems written in exile, one can hardly find either nostalgia for her life in Tehran or references to her adopted city Los Angeles. An exception is her poem “Many Happy Returns” written in 2004 in which past and present are combined:

Many Happy Returns

Five mornings a week

Fifty weeks of mornings

My sun rises

In the rear-view mirrors of buses

And each day in the old courthouse

Awaits me a small desk

An English-Farsi dictionary

A heap of summonses– a spiraling justice

And the relentless ringing of telephones.

On my cubicle wall

a tacked postcard

— White -flower stem on black background —

(Uproar of love between the lines on back )

A memory we lived

As Schubert

Passes through

My transistor radio.

On the opposite wall is an image

Of Maya Angelou, Ahmad Shamlou

Freeway maps

And a rendition of a love poem by Paz.

All day, wandering files

Are run through the copier

As are the throbbing of my tongue

In the veins of a most foreign language .

Each dusk, returning home

I halt passersby in search of

My lost days–

— In Los Angeles —

And ask the police

After that young woman

Whose hands were chained

In this house of fortune.

“Many Happy Returns!”

The voice of he Who is in love

Ripples through my house

Via the answering machine.

A feverish teardrop waters

A burnt jasmine leaf.

And then,

traipsing in books

And stitching clothes;

Reading, writing, cooking

Washing, scrubbing

Surfing the web

Typing, sewing

Weaving memories;

Thread to thread, one by one

Moss stitching:

One stitch over, one under

one row crimson

One the color of sorrow.

And when night falls

So the heaviness of habit

Scours not my spirit,

Hidden from the moon

I unstitch the old threads

And send my keen eye

Clad in a gilded gown

Off to tomorrow. (6)

Abbas Saffari was born in 1951 in Yazd. In his youth he wrote lyrics for the late avant-garde pop singer Farhad. He moved to the US in 1979 and lives with his American wife and their two children in Los Angeles. He ran a small waterproofing business until retirement. Saffari has been the poetry editor of two Persian literary magazines Sang and Kaktus while in exile. He has published several collections of poetry both in Iran and abroad including tarik-roshan-ye hozur (Twilight of Presence), Kebrit-e sukhteh (Burnt Matches) and durbin-e qadimi va she’r-ha-ye digar (Old Camera and Other Poems). Contrary to the other poets in this survey, he rarely writes political poems. In his poetry one finds many references to life in Los Angeles. In his last two collections of poetry, he has developed an appreciation for playing on words as well as a sense of humor, as seen in the following poem, published in 2005 in Burnt Matches:

Saturday Night Dinner

The onion, I will grate

To keep my stream of tears from drying.

The potato, you peel

For your sleight of hand with skin.

Let Nusrat Fatah Ali Khan, the Sufi minstrel play

For he opens us a window to Konya,

A window adorned with narcissus, sleepy-eyed and languorous,

And a handful of homing pigeons.

If they call

From MasterCard

Or the Internal I-don’t-have-any-Revenue Service

Tell them he’s gone to Kashmir

Looking for the long-lost polo ball of King Aurangzeeb of India,

And it’s unclear when he’ll be back.

Don’t laugh , my darling!

Cultural misunderstandings

Dismiss the disturber

Quicker than hollow conversation.

Now, while this aged Indian rice ripens,

Put two glasses, lip to lip, near our hands

Of our oldest vintage, four years old

And a reminder of a century past.

A sip of good wine

Is enough to erase an entire century from one’s memory.

Sip after sip

We can backtrack so far

That after dinner

We can find ourselves in the moonlight

Palm groves of Mesopotamia,

And around midnight

In a primordial place naked

And boundless. (7)

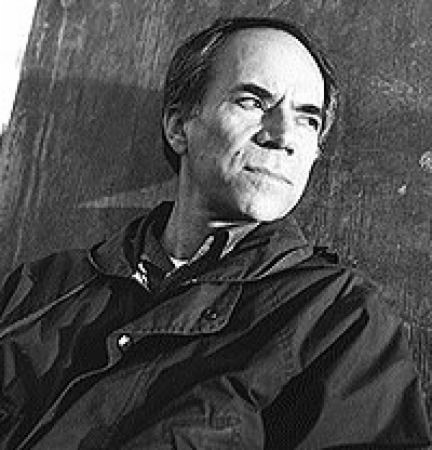

I, Majid Naficy, was born in 1952 in Isfahan. My first poems were published in Jong-e Isfahan when I was 13, and my first collection of poems dar pust-e babr (In the Tiger’s Skin) at 17. In 1983 I fled Iran, a year and a half after the execution of my wife Ezzat Tabaian in Evin Prison. I moved to Los Angeles in 1984 where I live with my son Azad. I have published two collections of poetry Muddy Shoes (Beyond Baroque Books 1999) and Father and Son (Red Hen Press 2003) as well as my doctoral dissertation Modernism and Ideology in Persian Literature: A Return to Nature in the Poetry of Nima Yushij (University Press of America 1997).

In June 1995, in a conference entitled “Writing in Exile” sponsored by The Institute for European-American Relations at University of Southern California in Los Angeles I had a talk called “A Reader Within Me” which I summarize here. (8) “When I fled Iran I brought my reader along with me. For half a decade, when I picked up my pen as a poet I was driven to write for that reader. Although he traveled abroad with me he still lived in Tehran, spoke only in Persian, preferred Iranian food and thought within the framework of Iranian culture. A good example of this can be found in my second collection of poems in Persian pas az khamushi). After the Silence published in 1986. Except for fewer than ten poems, all of the poems in this collection were written about the Iranian situation in the past and present. The poet is still haunted by the phantom of the lost revolution which was crushed by a new regime of theocracy. My body lived in L. A. but my soul was still rummaging through the ruins of a lost revolution in Iran. In my next collection of poems in Persian Anduh-e marz (Sorrow of the Border) published in 1989, the proportion of poems reflecting the new situation has increased drastically. In a very long poem, dedicated to my newborn son Azad, not only do I depict my bilingual world by including quotations in English within the body of the Persian text, but I also see my son as my own new root growing in my adopted country. In the next collection she’r-ha-ye venisi (Poems of Venice) published in 1991, the reader finds different aspects of life at Venice Beach where I lived for seven years. A turning point in this long journey from the realm of self-denial to acceptance and adaptation, is when I wrote a long poem on January 12, 1994 called “Ah, Los Angeles”. In 2000, the city of Venice engraved one fragment of this poem in a public space at a wall at Boardwalk and Brooks street. (9) In this poem, there is a reference to Parsees in Sanjan, India, by which I want to compare Iranians who emigrated to Los Angeles with Parsees, the descendants of Zoroastrians who during the Arab conquest of Iran emigrated to Gujarat, India. In 1599, Bahman Key Qobad, a Gujarati Parsee wrote an epic in Persian in which he narrated the voyage of Parsees’ ancestors from the Strait of Hormuz in the Persian Gulf to the port of Sanjan in Gujarat. Here is the revised version of the poem first published in Muddy Shoes in English:

Ah, Los Angeles

Ah, Los Angeles!

I accept you as my city,

And after ten years

I am at peace with you.

Waiting without fear

I lean back against the bus post.

And I become lost

In the sounds of your midnight.

A man gets off Blue Bus 1

And crosses to this side

To take Brown Bus 4.

Perhaps he too is coming back

From his nights on campus.

On the way he has sobbed

Into a blank letter.

And from the seat behind

He has heard the voice of a woman

With a familiar accent.

On Brown Bus 4 it rains.

A woman is talking to her umbrella

And a man ceaselessly flushes a toilet.

I told Carlos yesterday,

“Your clanging cart

Wakes me up in the morning.”

He collects cans

And wants to go back to Cuba.

From the Promenade

Comes the sound of my homeless man.

He sings the blues

And plays guitar.

Where in the world can I hear

The black moaning of the saxophone

Alongside the Chinese chimes?

And see this warm olive skin

Through blue eyes?

The easy-moving doves

Rest on the empty benches.

They stare at the dinosaur

Who sprays stale water on our kids.

Marziyeh sings from a Persian market

I return,homesick

And I put my feet

On your back.

Ah, Los Angeles!

I feel your blood.

You taught me to get up

Look at my beautiful legs

And along with the marathon

Run on your broad shoulders.

Once I got tired of life

I coiled up under my blanket

And remained shut-off for two nights.

Then, my neighbor turned on NPR

And I heard of a Russian poet

Who in a death camp,

Could not write his poems

But his wife learned them by heart.

Will Âzad read my poetry?

On the days that I take him to school,

He sees the bus number from far off.

And calls me to get in line.

At night he stays under the shower

And lets the drops of water

Spray on his small body.

Sometimes we go to the beach.

He bikes and I skate.

He buys a Pepsi from a machine

And gives me one sip.

Yesterday we went to Romteen’s house.

His father is a Parsee from India.

He wore sadra and kusti

While he was painting the house.

On that little stool

He looked like a Zoroastrian

Rowing from Hormuz to Sanjan.

Ah, Los Angeles!

Let me bend down and put my ear

To your warm skin.

Perhaps in you

I will find my own Sanjan.

No, it’s not a ship touching

Against the rocky shore;

It’s the rumbling Blue Bus 8.

I know.

I will get off at Idaho

And will pass the shopping carts

Left by the homeless

I will climb the stairs

And will open the door.

I will start the answering machine

And in the dark

I will wait like a fisherman. (10)

January 2012

1. “Odyssey or Aeneid? A Look into Mansour Khaksar’s Los Angelesinos” in Majid Naficy she’r va siasat va bist-o chahar maqaleh-ye digar (Poetry and Politics and Twenty-Four Other Essays) Sweden, Baran publisher, 2000

2. “Lamenting for a Poet in Exile” in Majid Naficy man khod iran hastam va si-o panj maqaleh-ye digar (I Am Iran Alone and Thirty-Five Other Essays), Toronto, Afra-Pegah publishers, 2006

3. Naderpour has dedicated this poem to Majid Amini who translated it into English for me. I edited his translation here.

4. Khosrow Davami, An entry on Mansour Khaksar in Encyclopedia Iranica online

5. The translation is mine.

6. Belonging: New Poetry by Iranians Around the World Edited and Translated by Niloufar Talebi, North Atlantic Books, 2008 7. Translated by Niloufar Talebi in Strange Times, My Dear: The Pen Anthology of Contemporary Iranian Literature Edited by Nahid Mozaffari and Ahmad Karimi-Hakkak Arcade Publishing, 2005

8. “A Reader Within Me” in Majid Naficy Muddy Shoes Beyond Baroque Books, 1999

9. Louise Steinman Poet of the Revolution: Majid Naficy’s Tragic Journey Home LA Weekly, February 15, 2001. Available online.

10. Majid Naficy Muddy Shoes Beyond Baroque Books, 1999.