|

| Federico García Lorca |

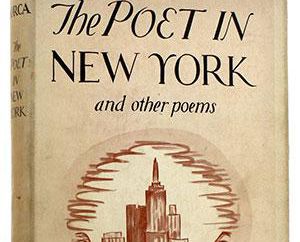

‘Poet in New York’ the way García Lorca conceived it

For the first time ever, bookstores will be selling the collection of poems that the Spanish writer gave to his publisher just weeks before dying

Jesús Ruiz Mantilla

Madrid, 27 March 2013

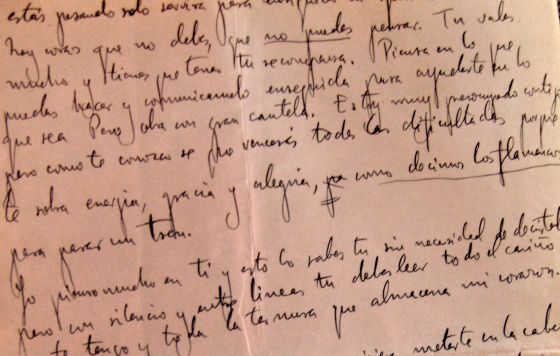

When Federico García Lorca walked into the office of José Bergamín on the eve of July 13, 1936 and failed to find him there, he left behind a written note: “I dropped by to see you and I think I’ll come back tomorrow.”

But tomorrow never came.

The poet left Madrid for Granada just a few days before civil war broke out. He naïvely felt that he would be safer back home.

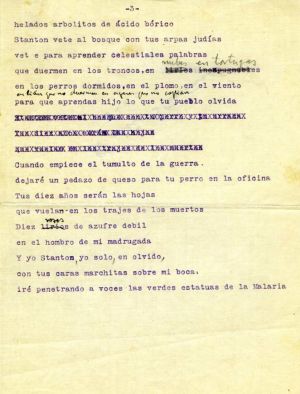

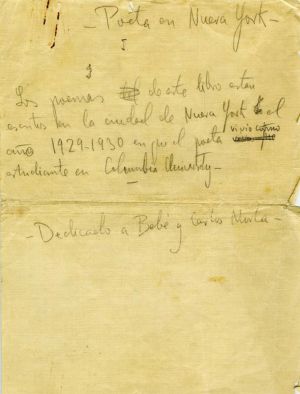

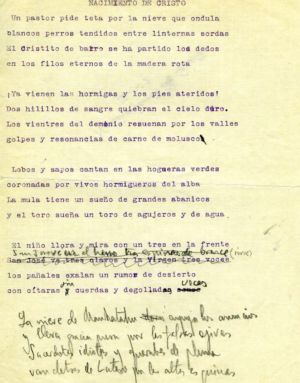

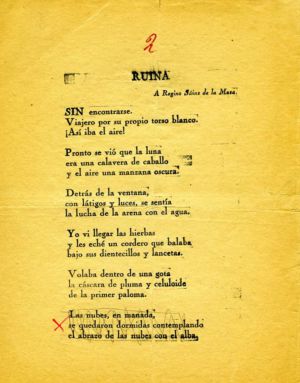

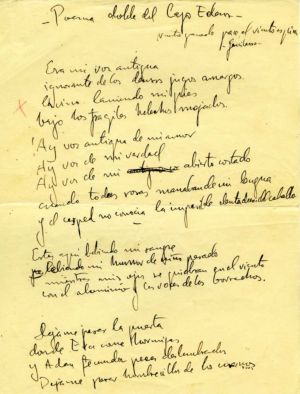

What he left his publisher on the table inside the newsroom of Cruz y Rayamagazine was the original manuscript – partly handwritten, partly typed, broken down into several parts and structured into 35 poems and 10 sections – of a masterpiece that was to change literature forever: Poet in New York.

Many will be familiar with the rest of the story; Lorca was executed on August 19 by right-wing forces, the original manuscript underwent all sorts of vicissitudes, and until now Poet in New York had never been published in the way that its author desired.

The book was originally going to be titled Introduction to death

After being lost for years, the original text finally emerged in 2003. The García Lorca Foundation bought it at auction for 194,000 euros. Until that June day, Lorca’s real intentions regarding this work had been shrouded in controversy and mystery.

But this week, Galaxia Gutenberg / Círculo de Lectores will deliver to bookstores the version of Poet in New York that Lorca himself would have liked to have held in his hands. The book comes with a meticulous analysis by Professor Andrew A. Anderson of Virginia University, and facsimiles of the original document where one can make out the handwritten lines and Lorca’s manual corrections over the typed text.

On Pablo Neruda’s recommendation, the book was originally going to be titled Introducción a la muerte (or Introduction to death). It was too premonitory, though inevitably truthful, and it was later toned down. The result is an unfinished work –the author and the publisher would have normally worked together to give it its final shape – although that does not make it any less valuable, striking or crucial.

The manuscript underwent an epic journey worthy of a chanson de geste. When war broke out, Bergamín went into exile, taking with him the poems that Lorca had conceived while staying at Columbia University for nine months in 1929-30, coinciding with the stock market crash and the onset of the Great Depression. “Lorca wanted most of them to be included [in the book], but not all of them. The excess ones have been referred to as orphans,” says Anderson.

Bergamín tried to get the book published in Paris, but his efforts were stymied by the hassle of his new life abroad and, very likely, by his inability to locate a few poems that Lorca had said he wanted to include but without providing a copy of them. During that time, however, two typed versions were produced that later served as the basis for the first editions of Poet in New York.

Bergamín later traveled to Mexico. “When he was there, Bergamín gave away the manuscript to Jesús de Ussía, who had provided financial support for his publishing house, Ediciones Séneca. Years later, when Ussía left Mexico, he left his personal possessions, including the Lorca manuscript, with a relative, Ernesto de Oteyza,” says Anderson. His widow then gave it away to the actress Manolita Saavedra, who kept it in her house in Cuernavaca until the 1990s. When Saavedra realized that a lot of people were searching for this manuscript, she decided to sell it. It went out on auction in 1999, but was not purchased by the foundation until 2003.

It was then that the text began to be carefully analyzed. This document contained the answers to the criticism that Bergamín had to endure after betraying the author’s intentions, at least according to many people. There were decisions that Bergamín made out of pure need, since some poems (like Crucifixión, purchased at auction by the Culture Ministry in 2007) were lost and could not be included in the volume. Although Lorca himself had demanded the original back from Miguel Benítez Inglott after giving it to him as a gift, he got no reply.

In the end, Poet in New York saw the light, and it included 32 poems

“In general, the criticism has not been fair. We were unaware of all the details of the process, and without that appreciation it is difficult to pass judgment,” adds Anderson.

The story of how Poet in New York was finally published is also worth telling. Between 1930 and 1935, there were numerous references to the book that Lorca had written during his US stay, and which he wanted to get published. But war prevented that last, necessary meeting between writer and publisher. Gathering the poems together was quite a feat, since the “to-be-included” list was left incomplete and Lorca had given some of the poems away to friends, or else sent them to magazines for individual publication.

In the end, Poet in New York saw the light, and it included 32 poems. It was first published in the US in 1940 and almost simultaneously in Mexico, where Bergamín had landed with a delegation of the Spanish Culture Junta, of which he was its first chairman. In Mexico, Bergamín founded the publishing house Séneca, which was loyal to the principles of Ediciones del Árbol, the Spanish company that would have put out the book there, had it not been for the war.

During his stay in New York, he offered the world premiere of the book to the publisher William Warder Norton, who took him up on it. But it was the Mexican edition that drew the most criticism, especially because of the editing work by fellow poet Emilio Prados, says Anderson, noting that that Prados changed several elements in the original, corrected the punctuation and included more than one appendix.

Despite so many setbacks, the book was already starting to leave a mark. “It has inspired many poets of different nationalities and from different eras,” says Andersen. “With Residencia en la tierra I and II, we get the epitome of a certain type of avant-garde style during these years. In many ways, this text is very comparable to T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land. Thanks to the second translation into English, dating from 1955, it influenced many US poets.”

Now, after a lifetime of coming and going punctuated by question marks and controversy, the wider public will finally have access to, if not the last word, then the next-to-last word by Lorca regarding his definitive conception of his most open, universal yet enigmatic body of poems.

Asesinado por el cielo (murdered by the sky), he wrote in the first verse of Vuelta de paseo (or, Back from a walk), as he explored his own solitude and amazement at Columbia University, where he gestated most of these poems. Now that his dream edition is about to see the light, perhaps the poet can rest a little more in peace, wherever he may be.

A LEGENDARY TRIP

- Federico García Lorca left his native Spain for the first time in the summer of 1929.

- After a fleeting stay in Paris, the poet arrived in New York, where he spent at least nine months. He stayed at a student residence in Columbia University.

-In March 1930 he took a train on his way to Cuba. From Key West, in Florida, he boarded a ferry that took him to Havana, where he spent around three months.

- An ocean liner brought the writer (and the manuscript that now sees the light) to the port of Cádiz in July of that same year. Back in Spain, Lorca was in no hurry to get Poet in New York published.